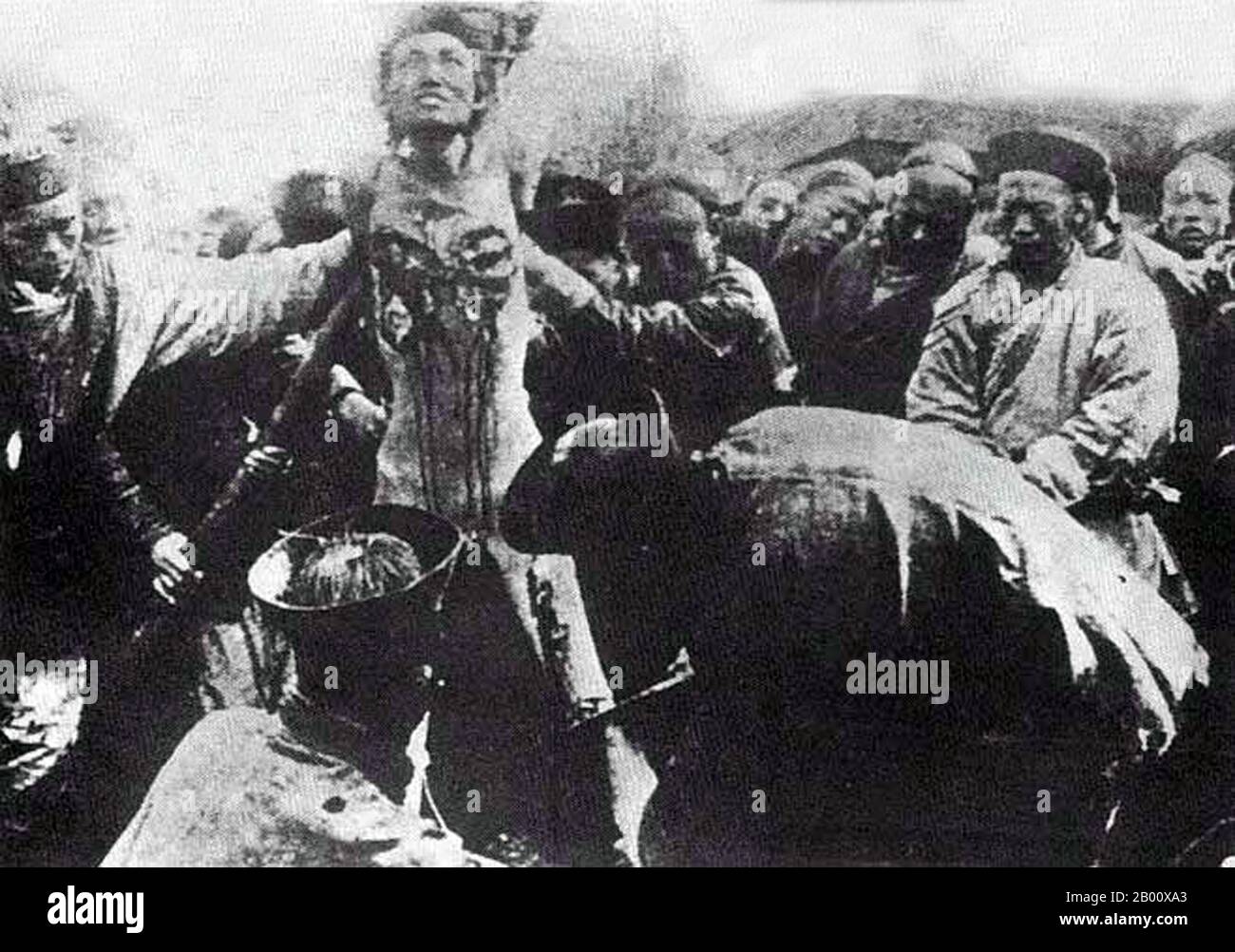

China: An execution by the 'Death of a Thousand Cuts', late Qing period, c. 1905. 'Slow slicing' (pinyin: língchí, alternately transliterated Ling Chi or Leng T'che), also translated as the slow process, the lingering death, or death by a thousand cuts, was a form of execution used in China from roughly 900 CE until its abolition in 1905. In this form of execution, the condemned person was killed by using a knife to methodically remove portions of the body over an extended period of time. The term língchí derives from a classical description of ascending a mountain slowly.

Image details

Contributor:

CPA Media Pte Ltd / Alamy Stock PhotoImage ID:

2B00XA3File size:

50.2 MB (1.2 MB Compressed download)Releases:

Model - no | Property - noDo I need a release?Dimensions:

5000 x 3511 px | 42.3 x 29.7 cm | 16.7 x 11.7 inches | 300dpiPhotographer:

Pictures From HistoryMore information:

This image could have imperfections as it’s either historical or reportage.

'Slow slicing' (pinyin: língchí, alternately transliterated Ling Chi or Leng T'che), also translated as the slow process, the lingering death, or death by a thousand cuts, was a form of execution used in China from roughly 900 CE until its abolition in 1905. In this form of execution, the condemned person was killed by using a knife to methodically remove portions of the body over an extended period of time. The term língchí derives from a classical description of ascending a mountain slowly. Lingchi was reserved for crimes viewed as especially severe, such as treason and killing one's parents. The process involved tying the person to be executed to a wooden frame, usually in a public place. The flesh was then cut from the body in multiple slices in a process that was not specified in detail in Chinese law and therefore most likely varied. In later times, opium was sometimes administered either as an act of mercy or as a way of preventing fainting. The punishment worked on three levels: as a form of public humiliation, as a slow and lingering death, and as a punishment after death. The latter as to be cut to pieces meant that the body of the victim would not be 'whole' in a spiritual life after death.