It is not possible to overstate the influence of Paul Cézanne on twentieth-century art. He’s the modern Giotto, someone who shattered one kind of picture-making and invented a new one that the world followed. Matisse called Cézanne “a sort of God”; Picasso said he was “the father of us all.” Max Beckmann called him “the last old master … the first new master.” He’s also an artist who can be hard to come to terms with: Great art often looks ugly when first seen, and Cézanne’s is an extreme case, so much so that his work can still vex. His optical disequilibrium made peers dubious, friends skeptical, and critics jeer.

Twelve stunning Cézanne canvases are now up at the Metropolitan, in a teensy show centered on three of his five Card Players paintings. They’re fantastic, even if they’re not my favorite Cézannes—those would be the bathers, still lifes, and landscapes—and they precisely mark a turning point in the history of art. These quietly grand insurrectionary works were made around Aix-en-Provence in the 1890s, when Cézanne was in his fifties and growing sickly. He had, by then, been virtually abandoned by increasingly successful Impressionist colleagues, who felt that the public ridicule his work attracted reflected poorly on their group exhibition. (In his time, he was attacked far more than Van Gogh was.)

What we see here is the beginning of a new way of seeing. Cézanne was a renegade in every way. He rejected both those who came before him—the giants Ingres and David, with their smooth surfaces, utterly lacking brushstrokes—and those who painted alongside him, the Impressionists and Postimpressionists, with their repeating patterns and brushwork. He didn’t care about narrative, place, commentary, sentimentality, or logical perspective. As Ellsworth Kelly has remarked, Cézanne “come[s] to terms with this visual chaos.” Parts of these canvases remain nearly blank; objects are depicted from multiple angles; planes tilt and break. In these difficult little paintings, Cézanne is depicting the pure forms his eye beholds in the milliseconds before the mind identifies or names them. Doing so was an Einsteinian leap, one that, he said, made the world “collapse.”

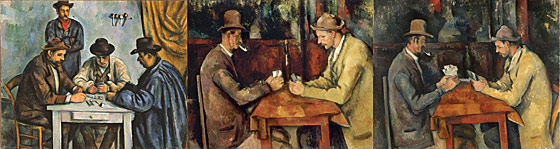

You can see that begin to happen in the 1892–96 Card Players that’s on loan from the Musée d’Orsay. Small but brimming with amplitude and grandeur, it shows two men facing one another at a wooden table covered with a stiff butterscotch oilcloth. The man on the right is stolid, wears tawny colors, and is bent forward; we can’t see his cards or chair. The man on the left is dressed in darker shades, wears a well-formed bowler, is more upright and angular, and shows his (blurred) cards and chair. The tabletop is perpendicular to the painting’s face yet turned at an oblique angle. The background is a void, all blues and greens. The figures could be in a café, a studio, or in front of a window or another painting. Compare this to the Met’s great earlier (1890–92) version of the same subject, in which we see three players and one observer. Notice the complicated angled vectors running through the painting, the twists, slight turns, shallow telescoping of this more enclosed space, the ways in which parts of the scene seem to flutter. Then when you get to the third Card Players on view—the one owned by the Courtauld Gallery, in London, which (new scholarship reveals) was probably painted last—reality caves in. The table floats; the wine bottle blends with the wall that melds into the background as the players are left in some stony state of suspended animation, as if their cards were Medusa heads.

I love the Met’s Card Players for its opulent Veronese color and visual complexity. I love the d’Orsay painting more for the contrapuntal composition that electrifies the painting. But I love the Courtauld’s version most, because it reveals the deep content of all three most clearly. As he moves from the Met’s large painting to the Courtauld’s smaller one, Cézanne bids farewell to making straightforward pictures of anything, and the long good-bye plays out before your eyes. The Card Players paintings aren’t about something; they are painting as something, and you can see why, twenty years after the Impressionists dismissed him, the Cubists rediscovered and celebrated him. Like great Egyptian art, Assyrian reliefs, early Christian mosaics, or the Greek kouros, Cézanne roused us from one spatial-temporal dimension into another. He gives us shuddering silence, matter coming into being, and what Hart Crane called “the broken world.”

Cézanne’s Card Players

The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Through May 8.