The Story of the Tamil bell

N D Logasundaram

on Wednesday, 18 March 2015. Posted in Inscriptions

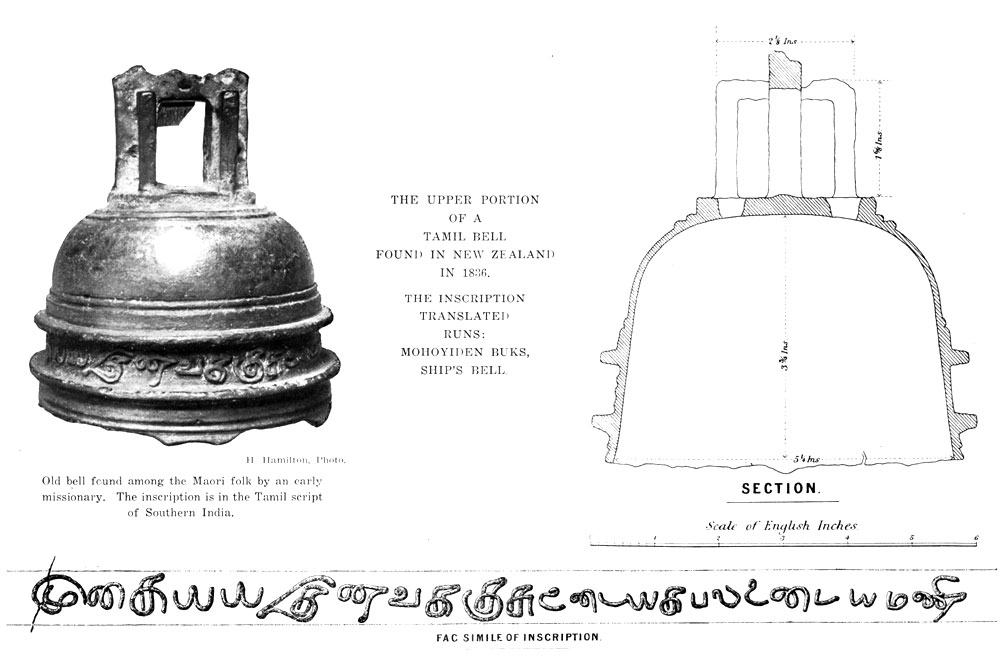

The subject of this communication is a bronze bell, 166 mm high and 153 mm in diameter, carrying an inscription in ancient Tamil characters. The lower part of the lip or skirt was cracked off at an unknown date, which may have decreased the height by 40 or 60 mm. Since 1890, the bell has been in the possession of the Dominion Museum at Wellington, the gift or bequest of William Colenso, 1 who had found the bell in a Maori village. How it reached New Zealand is a mystery which has intrigued many scholars. Apart from the possibility that the bell was taken to New Zealand by Europeans after 1800, there are at least two theories, one by the author, and the other more recently proposed by the writer Robert Langdon. 2 Perhaps the earliest reference to the bell was by John Crawfurd in 1867. 3 I am indebted to the director and officers of the Dominion Museum for personal communications on the subject of the bell.

William Colenso says that he found Maoris using the bell as a cooking pot in a village which he thought had not previously been visited by Europeans. The date was thought to have been 1836 or 1837 (the most recent estimate given is 1840). The village was either “near Whangarei” or “in the interior of the North Island”. The Maoris told Colenso that the bell had been found in the roots of a large tree which had been blown over in a storm many years before. It appears to me possible that the use of the bell as a cooking pot, with the resultant changes of temperature, may have caused the lip to crack off. Presumably the bell had been hidden under the tree for a long period. As the inscription (see below) tells us that it is a ship's bell, I presume that the ship which owned it was probably wrecked on the west coast. It has been thought that a section of wreckage, of teak timber with trenails, could have been the Tamil ship which carried the bell, but this wreckage has since been connected with H.M.S. Orpheus wrecked on the Manukau Bar in 1863. There is little chance of finding a wreck with evidence of Tamil origin, especially as such a ship would have been wrecked about 500 years ago.

As the inscription is the vital clue for the story of the bell, it will be described in some detail. The inscription, which does not run right around the bell, has been protected by flanges running above and below the lettering, which explains why it is still in almost “mint” condition. Instead of the letters being cut into the bronze after casing, they protrude from the surface as though they had been added later. - 478  Some of the letters appear to show file marks, and where they should have rectangular form they are made with curved lines like the rest of the lettering. Another variation from standard Tamil writing is that four letters which should carry dots over them are left without them. Reading from left to right, there are 24 letters in all, forming six or seven words. The first 11 letters form the name of the ship's owner, in two or possibly three words; the remaining 13 letters relate to the ship and the bell itself.

Some of the letters appear to show file marks, and where they should have rectangular form they are made with curved lines like the rest of the lettering. Another variation from standard Tamil writing is that four letters which should carry dots over them are left without them. Reading from left to right, there are 24 letters in all, forming six or seven words. The first 11 letters form the name of the ship's owner, in two or possibly three words; the remaining 13 letters relate to the ship and the bell itself.

The inscription suggests that the owner was a Moslem Tamil, probably from one of the well-known ship-owning families based on the port of Nagapattam on the eastern coast of Tamiland in south-east India. As the owner's name was probably an Arabic one, in accord with his religion, the founder of the bell would have had difficulty in converting it from the Arabic alphabet into Tamil letters. Arabic writing consists of consonants only, while Tamil writing has a syllabary rather than an alphabet.

There is a similar difficulty in converting Tamil characters into the European alphabet, as, in many cases, Tamil consonants and vowels are equivalent to three or four different letters. In the transliteration which follows, each Tamil character represents a consonant with a vowel, except that a character carrying a dot over it is a consonant alone. My own attempt at translation was made possible by the excellent photographs provided by the Dominion Museum, and the advice of two leading experts on the script, Mr D. Yesudhas, M.A., of the Scott Christian College at Nagercoil, and Mr R. Raneer Selvam of the Scandinavian Institute of Asian Studies at Copenhagen, Denmark. Both of these experts dated the script on the bell between 1400 and 1500; Langdon 4 quotes Professor Visvanathan's estimate as 400 to 500 years before 1940, i.e. 1440-1540. Mr Selvam also provided some information about the ship-owning Tamils of the Moslem faith who were engaged in the Arab trade routes in that period. He suspected that the owner's first name may have been derived from Tamil words meaning “an owner of wooden ships”.

In the transliteration which follows, the inscription is divided into two parts. The first line in each case is a copy of the Tamil characters on the bell; the second line is the modern Tamil equivalent, and the third line is the most likely equivalent in European letters:

The two identical words in the lower line, “Utaiya”, mean “owning” or “possessing”; “Kappal” means “ship” and “Mani” means “bell”. The upper line, being the owner's name, has been translated by various authorities through the years as “Mohammet Buks”, “Hohoyiden Buks”, “Muhideen Bhakshi” and “Moha Din Buksh”. My own preferred translation is “Mohaideen Bakhsh”, with a second possibility as “Moha Din Bakhsh”. The full inscription therefore can be read “Bell of the Ship of Mohaideen Bakhsh”. The date of casting can be placed at c.1450.

Before 1400, the trade to Java was in Indian hands. During this period the natives of Java and Bali became first Buddhists and later Hindus. After 1400, with the spread of Islam, this trade came to be dominated by the Arabs. Some early Indian vessels are shown in the stone carvings of the great Buddhist temple of Borobodoer, dating back to about A.D.500. Some of these vessels appear to be catamarans or outrigger canoes, but one at least is a two-masted vessel under sail. Tamil trading ships of 1400 and later may have been larger, and may have owed something to Arab methods of ship-construction.

In addition to trading between India, Malaya and Java, many Moslem Indians were plying the trade routes around the shores of the Indian Ocean and down the east coast of Africa as far as Sofala, opposite the southern tip of Madagascar, which was the western limit of Arab trading. Many Indians rose to prominence in the Islamic empire; the greatest Arab navigator of all time, Ibn Madjid, was a Gujerati born in Oman c.1450. The Arab monopoly of trade ceased with the influx of the Portuguese c.1500.

The question of how the Tamil Bell got to New Zealand has never been answered. It hardly seems possible that the bell arrived in New Zealand in a European ship at a date early enough for Colenso to obtain it as an old relic in 1836 or even 1840. As far as we know, the eastern limit of Indian contact was at the island of Lombok, next to Bali. Although the trade routes to the Spice Islands and West New Guinea had been in use for thousands of years, this trade was mainly in the hands of the local rulers of Ternate, Tidore and Amboyna. Some ancient petroglyphs in the Fiji Islands have been thought to be early Indian or Chinese scripts, but they have not been identified or deciphered, nor has any explanation been found for them. No Indian relics except the bell have been found in New Zealand, so the problem remains unique and unsolved.

In his book The Lost Caravel, Robert Langdon propounds a theory to solve the problem. He claims that the bell was taken as a souvenir from the East Indies to Spain, and later brought into the Pacific by a caravel which was wrecked in the Tuamotu group. From there he proposes that it was carried in stages to New Zealand by some of the survivors or their descendants as part of their Spanish culture. The date would presumably have been 1550. This theory appears at first sight to be very far-fetched; however it does link the bell with another relic, the Spanish helmet found in Wellington Harbour. In January 1970, I suggested that the bell might have belonged to a ship in the Indian Ocean which had become a derelict, probably abandoned, dismasted and waterlogged. Such a vessel could have drifted the 5000 miles to the west coast of New Zealand. This led me to assume that the bell came to New Zealand in the ship to which it belonged, namely the ship of Mohaideen Bakhsh. The details of, and evidence for, this theory are given below.

Most writers and historians assume that a wrecked ship has come to grief under full sail and with the crew aboard. However, this assumption neglects the fact that in the days of wooden ships many vessels went missing in storms — a considerable number would have been dismasted, overwhelmed by seas, and abandoned with decks awash, and yet the buoyancy of the wooden hull would have kept them afloat for many years, if the cargo and ballast they were carrying were not heavy enough to sink them.

Such derelicts drifted the seas and oceans of the world and were hazards to shipping. Some were found, and destroyed by naval vessels. Others continued to drift until they broke up in heavy seas or were cast ashore. Most stretches of coast are littered with driftwood from damaged or wrecked ships, including the hundreds of vessels which have gone missing through the centuries without trace and without any survivors to tell the tale.

Among the derelicts which have been reported are the Flying Dutchman, still under full sail but with all the crew dead, the legendary ships caught in the vortex of the Sargasso Sea, and the well-documented Mary Celeste. Nearer home, there is the case of the Joyita, lost on a voyage from Apia to the Tokelau Islands, and found four months later without a soul aboard, half submerged in the sea.

Derelicts are carried along by the permanent currents in the sea, most of which are known and charted from years of observation from ships and by the drift of sealed bottles. The currents, shown on a special Admiralty Chart, tend to follow circular tracks in each ocean, flowing along with the prevailing winds, with some seasonal variations caused by the monsoons. The largest of these currents, and the one of most importance in my theory, is that which runs right round the southern part of the world between the coast of Antarctica and the southern continents. This is the area of regular westerlies, known as the “Roaring Forties” and “Shrieking Fifties” after the latitudes in which they are found. These westerlies produce a current running to the eastward with a speed of half a knot or more. Although this is not a great speed, any derelict drifting in it, with some help from the wind, will travel for thousands of miles in due course.

Two examples of the drifts possible in the great Southern Current have recently been reported in the Nautical Magazine of Glasgow. In the issue for June 1973 there appears the following account of the drift of an unmanned lifeboat: 5

FIGURE 2

FIGURE 2

The position from which the lifeboat began her long drift is off the south-east corner of Africa in the region of the Agulhas Current, which runs south and joins the great Southern Current on its route towards Australia. The distance of 7000 miles, presumably expressed in land miles, gives a speed of about half a knot, but this does not allow for any variations in the track followed. This drift is a good indication of the probable drift route for a derelict from the Arab trade routes in the Indian Ocean and down the east coast of Africa. During a long period, a derelict might well make a few circuits of the Indian Ocean before joining the Agulhas Current, for anything drifting to the south-west corner of Australia could there be carried northwards into the India Ocean circuit. The lifeboat may easily have capsized more than once in her waterlogged state, while only her air-tanks held her steel hull from sinking completely.

The second example, also reported in Nautical Magazine 6, is of an even greater drift:

The drifting bottle, allowing for some variations from the shortest track, also averaged about half a knot. Its significance is in showing that a ship lost or abandoned off Cape Horn, or in Magellan Strait, could also drift to Australia and beyond, even right round the world. Many ships were lost near Cape Horn during the early expeditions of the Portuguese, Spanish and English, as all the attempts at circumnavigation, including Cook's first voyage, were from east to west, against the prevailing winds and currents. Captain Bligh in the Bounty gave up the struggle off Cape Horn and turned eastwards to the Cape of Good Hope and on to Tahiti. The timbers of some of the ships lost near the Horn could well have reached the shores of Australia or New Zealand, and many drift bottles have probably done the same in the long process of plotting the currents of the oceans and their rate of drift.

A further possible example of the drift from the Indian Ocean is the case of the so-called “Mahogany Ship” near Warrnambool, Victoria, only 40 miles east of Portland, where the above-mentioned drift-bottle was picked up. The Mahogany Ship was one of three or four unidentified wrecks between Warrnambool and Port Fairy whose details have become confused and merged in the legends of the ancient wreck referred to since 1890 as the Mahogany Ship. This wreck was first seen in 1836, high in the sand hills and hundreds of yards from the sea. Her - 483  timbers were obviously very ancient and what could be seen of the bulwarks and remains of her poop appeared to be mahogany, although one witness wrote “cedar or mahogany” in 1876. What could be observed of her style of construction was quite foreign to the whalemen and other early witnesses, but she had two masts and some decking, and being about 100 feet in length was presumably about 100 tons or more. Owing to the effects of souvenir hunters and the accumulation of drift sand by the wind, the wreck has not been seen since 1880 when a mining engineer estimated its height above sea level as 30 feet.

timbers were obviously very ancient and what could be seen of the bulwarks and remains of her poop appeared to be mahogany, although one witness wrote “cedar or mahogany” in 1876. What could be observed of her style of construction was quite foreign to the whalemen and other early witnesses, but she had two masts and some decking, and being about 100 feet in length was presumably about 100 tons or more. Owing to the effects of souvenir hunters and the accumulation of drift sand by the wind, the wreck has not been seen since 1880 when a mining engineer estimated its height above sea level as 30 feet.

Since 1890, various attempts have been made to find the Mahogany Ship. The latest was in January 1975, using sand-drills and other sophisticated instruments over the most likely areas. The few relics found in the neighbourhood, and possibly related to the wreck, include a porous pottery vase or water-pot with two graceful handles and a stopper. This item carries no pattern or marks except two rows of dots around the body. It is slightly similar to water-pots dating from 700 B.C. to recent times from India, Egypt and Africa.

The wreck was first assumed to have been a lost Portuguese, Spanish or Dutch vessel forced to sail along the unknown coastline before the time of Captain Cook. Recently it has been assumed to have been one of three Portugusee caravels commanded by Cristavao de Mendoca, who is reputed to have sailed from Malacca in 1522 to explore the area of the mythical Southland. People holding this theory believe that a series of early French charts drawn between 1530 and 1560, including one called the “Dauphin Map”, actually show the coasts of Australia, as far as Portland in Victoria, charted by Mendoca, None the less I believe that these charts are based only on the reports of Marco Polo, who wrote of a land with many elephants, probably referring to Malaya.

The situation of the Mahogany Ship suggests that she was thrown up ashore before the coastal sand hills were formed. The local Aborigines in 1840 said that the wreck had been there longer than their knowledge. I contend that the ship arrived off the coast as a derelict and was cast ashore in a great storm at least 500 years ago, possibly 1000 years B.P. The earliest European ship which could have been a derelict carried by the great Southern Current would have been from about 1490 when five caravels were lost in a storm on the Cape of Good Hope. Some of the survivors reached Sofala, opposite the southern tip of Madagascar, the most southerly trading post of the Arabs. Their expedition is not recorded in Portuguese history, but appears in Arab records.

In and before 1490, the whole trade of the Indian Ocean shores was carried in Arab and Indian vessels. Therefore I consider that the Mahogany Ship was one of these vessels, lost and abandoned, left to drift dismasted and waterlogged on the ocean currents. If and when the remains of the Mahogany Ship are located and investigated, we may get a good idea from her timbers of her age and the place she was built and possibly some idea of her trade from any relics still in her bilges or in the nearby sand. Probably she was inspected by Aborigines soon after her arrival. Perhaps they took some small souvenirs a short distance away, and then discarded them. Is this what happened in New Zealand to the Tamil Bell?