David Cameron and Nick Clegg are now entirely focused on how they can cling on to power even if their coalition government loses its Commons majority, Labour officials have claimed.

The polls are consistently indicating a hung parliament, with the Tories gaining slightly more seats than Labour but the Liberal Democrats losing so many that a combined Tory-Lib Dem coalition would not get a majority in the Commons.

There are now reports that Cameron will in this scenario insist on staying on in Downing Street regardless of his ability to pass laws in the Commons, rather than allow Labour a chance to form a government – leading to a constitutional gridlock. A senior Labour official said: “All the noise coming out of the mouths of David Cameron and Nick Clegg is about how they can cling on to power even if their coalition loses its majority.

“Clegg has shown his true colours – he personally wants to get back into bed with Cameron even at the price of betraying the Lib Dems’ fundamental principle of protecting our future in Europe.”

The Labour official added: “David Cameron is showing he is in an incredibly weak position. He won’t talk about the big questions in this election, how to create an economy which works for working families, how to sustain our NHS, how to get a better future for young people.

“Instead, he is trying to focus all attention in these final days on the process question of what happens after the election rather the decision people have to make in this election.

“Just like he did on the morning of 19 September – where Cameron had the opportunity to speak for the whole country after the Scottish referendum – he is instead showing he is driven by internal weakness and external electoral pressure to act only on behalf of the Tory party.”

The warnings are a response to briefings coming from Downing Street that Labour will have no legitimacy to form a government if it has secured fewer seats than Cameron, and should let through a Tory Queen’s Speech possibly with the support of the Liberal Democrats.

The Times claimed that Labour front benchers are privately admitting Miliband will have to admit defeat if he is 15 seats behind the Tories.

There is clearly a fear in Labour circles that Cameron intends to stay in Downing Street not just to see if he can form a majority government with the Liberal Democrats and Democratic Unionists, but also to prosecute a claim that an alternative minority Labour government would have no legitimacy.

There is concern that the prime minister will not quit even if it is clear he could not secure a Commons majority in a Queen’s Speech that must be held by 4 June.

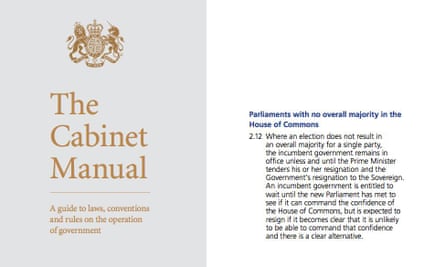

It is argued that the Cabinet Manual – the civil service book setting out the rules on the transfer of power – states a prime minister can stay only until the point at which it is clear they cannot command the confidence of the Commons; not when any other party demonstrates they can form a majority or requires a vote in the House.

The relevant section of the manual states: “Where an election does not result in an overall majority for a single party, the incumbent government remains in office unless and until the prime minister tenders his or her resignation and the government’s resignation to the sovereign. An incumbent government is entitled to wait until the new parliament has met to see if it can command the confidence of the House of Commons, but is expected to resign if it becomes clear that it is unlikely to be able to command that confidence and there is a clear alternative.”

The argument will then turn on whether convention expects the prime minister to resign as soon as it is clear that they no longer command a majority. Some argue precedent, with expert opinionsaying the leader of the largest opposition party will be appointed prime minister.

This is the key passage from the manual – that a prime minister’s ability to stay on is only up until the point at which it is clear they cannot command the confidence of the Commons, and not when any other party demonstrates it can form a majority or requires a vote in the House.

The experts are clear in their analysis of the situation. Professor Robert Hazell, director of the Constitution Unit, said:

There’s no rule which says the largest single party has the right to form the next government. There is not even a rule which says it has the right to first go. Negotiations are freestyle, and no party can claim the right to be the first mover. The Queen will appoint as prime minister that person who can command the confidence of the House of Commons. That need not necessarily be the leader of the largest single party, if someone else can command the support of a wider group in the Commons.

Vernon Bogdanor, the Professor at the Institute for Contemporary History at King’s College, London, said:

The rules are very clear. The government is legitimate if it commands the support of parliament. In 1910, when Liberals and Conservatives had roughly the same number of votes, the Liberals governed with the support of the Irish Nationalists and Labour and no one questioned the legitimacy of that.

What would be the situation otherwise? Would it mean that the Labour party should abstain on the Queen’s Speech so that Cameron should be able to govern even though the majority in parliament were against him? That would be absurd, wouldn’t it?

The rules are laid out and they are very clear. The incumbent prime minister can if he wishes meet parliament with a Queen’s Speech. If he is defeated on that, he resigns. The Queen calls for Ed Miliband. Miliband, in theory, could say he’s not going to form a government because it would only be with the aid of the Scottish nationalists but of course he wouldn’t do that. He would form a government and his programme would be put forward but there won’t, I think, be a second Queen’s Speech. Parliament would decide whether it supports it or not. If it doesn’t, there has to be another election. But there is probably little point in that because there is no reason to believe it would lead to a very different result. There may be political uncertainty but the constitutional rules are clear. There will be all sorts of scares, no doubt, as there were last time, but the coalition was set up and proved stable.

The key fact always to bear in mind is that we are a parliamentary system and there is a vote in parliament on what is to happen and that will be on the Queen’s Speech, and either Cameron or Miliband will present a Queen’s Speech. The question of who has the largest number of seats is not relevant in a multi-party situation. It is for parliament to decide. The public may or may not like a particular government that has formed. It would then be for the public to let their feelings be known in later elections.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion