Researchers have overcome one of the major stumbling blocks in artificial intelligence with a program that can learn one task after another using skills it acquires on the way.

Developed by Google’s AI company, DeepMind, the program has taken on a range of different tasks and performed almost as well as a human. Crucially, and uniquely, the AI does not forget how it solved past problems, and uses the knowledge to tackle new ones.

The AI is not capable of the general intelligence that humans draw on when they are faced with new challenges; its use of past lessons is more limited. But the work shows a way around a problem that had to be solved if researchers are ever to build so-called artificial general intelligence (AGI) machines that match human intelligence.

“If we’re going to have computer programs that are more intelligent and more useful, then they will have to have this ability to learn sequentially,” said James Kirkpatrick at DeepMind.

The ability to remember old skills and apply them to new tasks comes naturally to humans. A regular rollerblader might find ice skating a breeze because one skill helps the other. But recreating this ability in computers has proved a huge challenge for AI researchers. AI programs are typically one trick ponies that excel at one task, and one task only.

The problem arises because of the way AIs tend to work. Most AIs are based on programs called neural networks that learn how to perform tasks, such as playing chess or poker, through countless rounds of trial and error. But once a neural network is trained to play chess, it can only learn another game later by overwriting its chess-playing skills. It suffers from what AI researchers call “catastrophic forgetting”.

Without the ability to build one skill on another, AIs will never learn like people, or be flexible enough to master fresh problems the way humans can. “Humans and animals learn things one after the other and it’s a crucial factor which allows them to learn continually and to build upon their previous knowledge,” said Kirkpatrick.

To build the new AI, the researchers drew on studies from neuroscience which show that animals learn continually by preserving brain connections that are known to be important for skills learned in the past. The lessons learned in hiding from prey are crucial for survival, and mice would not last long if the know-how was erased by the skills needed to find food.

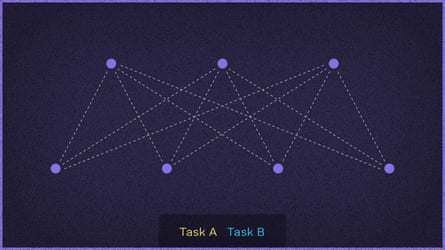

The DeepMind AI mirrors the learning brain in a simple way. Before it moves from one task to another, it works out which connections in its neural network have been the most important for the tasks it has learned so far. It then makes these harder to change as it learns the next skill. “If the network can reuse what it has learned then it will do,” said Kirkpatrick.

The researchers put the AI through its paces by letting it play 10 classic Atari games, including Breakout, Space Invaders and Defender, in random order. They found that after several days on each game, the AI was as good as a human player at typically seven of the games. Without the new memory consolidation approach, the AI barely learned to play one of them.

In watching the AI at play, the scientists noticed some interesting strategies. For instance, when it played Enduro, a car racing game that takes place through the daytime, at night, and in snowy conditions, the AI treated each as a different task.

Writing in the journal, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the researchers describe how the new AI solved problems with skills it had learned in the past. But it is not clear whether drawing on past skills made the AI perform better. While the program learned to play different games, it did not master each one as well as a dedicated AI would have. “We have demonstrated that it can learn tasks sequentially, but we haven’t shown that it learns them better because it learns them sequentially,” Kirkpatrick said. “There’s still room for improvement.”

One reason the AI did not nail each game was that it sometimes failed to appreciate how important certain connections were for its playing strategy. “We know that sequential learning is important, but we haven’t got to the next stage yet, which is to demonstrate the kind of learning that humans and animals can do. That is still a way off. But we know that one thing that was considered to be a big block is not insurmountable,” Kirkpatrick said.

“We are still a really long way from general-purpose artificial intelligence and there are many research challenges left to solve,” he added. “One key part of the puzzle is building systems that can learn to tackle new tasks and challenges while retaining the abilities that they have already learnt. This research is an early step in that direction, and could in time help us build problem-solving systems that can learn more flexibly and efficiently.”

Peter Dayan, director of the Gatsby Computational Neuroscience Unit at University College London, called the work “extremely nice”. He said that for computers to achieve AGI, they will need to learn how one task relates to another, so that past skills can efficiently be brought on bear on new problems.

Alan Winfield, at the Bristol Robotics Lab at the University of the West of England said the work was “wonderful”, but added: “I don’t believe it brings us significantly closer to AGI, since this work does not, nor does it claim to, show us how to generalise from one learned capability to another. Something you and I were able to do effortlessly as children.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion