Tāmaki Makaurau, the Māori name for Auckland which can be translated as “the place desired by many”, is living up to its billing. The city’s population has swelled rapidly to 1.7 million and is estimated to be adding 40,000 people a year. By 2048 it could host nearly half of New Zealand’s current population.

In the 1980s only a couple of thousand people lived in the central city. Now some 57,000 people call it home, a figure that was not expected to be reached until 2032.

Auckland is grappling to cope with that population growth. Traffic jams on clogged motorways can stretch into hours. Decades of under-funding of public transport has led to a patchwork and complicated system serving a total area of around about 1000 sq kms . The rising cost of living has spawned a growing homeless population, with some forced to live in parks or sleep in their cars, and garages are now rented out as accommodation for hundreds of dollars a week.

Paul Spoonley, a sociology professor at Massey University, says the harbour city is simply bulging at the seams. “Infrastructure and service provision simply has not kept up with the rate of population growth, but also because there’s been a historic deficit,” he says. “We haven’t had enough houses in Auckland for decades, and there hasn’t been a major investment in adequate public transport for a very long time.”

Jenna Todd, 34, and her husband, Stu, rent a home in Auckland’s Mount Roskill but are actively looking to buy. Todd lists Auckland’s “food, diversity, weather, and easy access to rural getaways” as the major reasons she loves the city.

Todd manages the popular Time Out bookstore in the inner-city suburb of Mount Eden, and has noted rising tension between suburban business areas such as hers “adapting to population growth – with higher density housing, developing alternative transport to cars – and the desire to preserve heritage, views and green spaces”.

“Auckland is spread out, which isolates our population into pockets,” says Todd, who broadly welcomes further growth of Auckland’s population, if better planning and infrastructure provisions are made. “We need to continue to connect suburbs with efficient public transport and safe cycleways, to encourage accessible movement throughout the city.

“I want people to travel to the Mount Eden village without worrying about clogged roads and parking to spend money at our locally owned businesses. I think Auckland won’t be able to compare with large, international cities until this happens.”

Auckland is regularly ranked as one of the best cities in the world to live in, but also one of the most expensive. Spoonley says the average cost of housing is nine times the average household income.

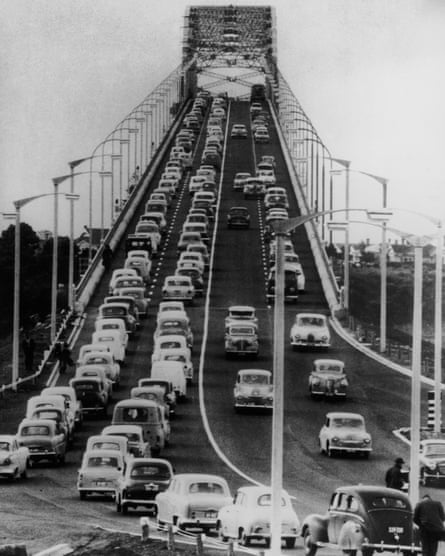

Until the 1950s, Auckland had a transport system that was the envy of the world. Its quarter of a million citizens took more than 100m trips a year, on ferries and buses but mainly on frequent, cheap, council-run trams to all points of the compass.

“Everyone took an average of nearly two trips per day,” says Ben van Bruggen, the Londoner now in charge of Auckland council’s urban design strategy. “That’s the kind of level that London Underground operates at.”

But the city tore up the tram lines and laid down motorways. It is only now, thanks to costly investment in public transport, that many are leaving their cars at home again. “To get back to 100m public transport trips last year, that’s quite a turnaround,” Van Bruggen says. “That’s doubled within 10 years.”

It doubled from a low base. The population is now nearly seven times that of the 50s, and per-capita patronage levels don’t approach those of Sydney or Melbourne, for example, let alone what they might have been if the trams had been retained. And it has come at a considerable cost.

Billions have been spent electrifying a suburban rail system, adding bus routes and a separate busway along the northern motorway, and shifting the terminus into the city centre. A further NZ$4bn (£2bn) of taxpayer and ratepayer money is being spent on converting the terminus into a loop that will double the network’s capacity by 2024. A few divided cycleways have gone in, and a long-delayed one across the harbour bridge and on to the northern suburbs is slated for next year.

But more is needed. Traffic congestion is a perennial complaint for commuters and costs hundreds of millions a year in productivity. “There is no more car capacity,” Van Bruggen says. Commitments have been made to new light rail lines in the next decade.

Commuters complain about the cost of short bus trips and that the rail network doesn’t go to enough suburbs, but South Auckland’s Phyllis Jaggard and Noelene Bowden are fans of the frequent and quiet electric trains over their “terrible, smelly diesel” predecessors. Jaggard hardly drives into the city because of better services and reduced parking. “It’s annoying when services get cancelled,” she says. “But every city in the world has this problem.”

The city is now home to 220 ethnicities, thanks in particular to migration from Asia. About 39% of Auckland residents were born overseas, according to Penny Pirritt, director of urban growth and housing at the council, compared with a national average of 27%. It is also home to almost a quarter of New Zealand’s Māori population and 65% of the nation’s Pacific peoples.

‘Getting out of its teenager angst’

Despite the challenges, Auckland is “maturing and moving quite quickly”, taking lessons from other global cities and its own earlier failures, Van Bruggen says. “It’s getting out of its teenager angst.”

Old chemical storages facilities are being turned into a medium-rise residential-commercial area called Wynyard Quarter. The city’s waterfront, which used to be fenced off to store imported used cars, is being opened up.

Some NZ$14bn of public and private development is going on in the city centre alone. Auckland council forecasts that the city could have 2.4 million people by 2048 and need a further 313,000 dwellings and up to 263,000 extra jobs.

Where will these homes go? Pirritt says the city this year approved the construction of more than 14,000 dwellings, the most since 2004. More than half are mixed-density models – townhouses, apartments, terraces and retirement villages – many close to public transport and community facilities. The city’s model plans for 70% of all future growth to be within existing urban areas.

A government-commissioned working group recommended in October moving the city’s port north, potentially freeing up 77 hectares of prime seafront land. The city has also earmarked 15,000 hectares for future urban development, largely in the north and south.

The city is also working with developers to provide affordable homes. A survey found Auckland contained 40,000 “ghost houses”, properties empty for much of the year.

Of course, many challenges still exist. Over half the country’s overcrowding is in Auckland and more than 20,000 people are estimated to suffer “severe housing deprivation”. Māori and Pacific peoples are overrepresented in homelessness figures. The population squeeze and traffic congestion are part of the reason more than 30,000 Aucklanders left for other parts of the country in the four years to 2017, many of them older Pākehā (New Zealanders of European descent), according to economist Benje Patterson.

Yet Auckland’s second-term mayor, Phil Goff, whose English immigrant grandfather drove a tram for 20 years, is upbeat. He told the Guardian: “You’re seeing a city that’s transforming, both in scale and how people want to live and how they want to get around it.”

He is proud of getting through a 10-year transport budget that has increased 50%, and fixing the city’s pipes to stop wastewater flowing into the harbours alongside stormwater. “It’s about making sure that as we grow we have the infrastructure in place so that you don’t get housing shortages, growing unaffordability and homelessness.”

The biggest challenge is revenue, he says. “We’re saying to government, you wanted a super city: this one is 35% of [New Zealand’s] population, 38% of its GDP; we’ve got to have a 21st century funding system so we can make this a world-class, truly liveable city.”

additional reporting by Harriet Sherwood

This article was amended on 28 November 2019. The original attributed a reference to Auckland’s population squeeze to demographer Natalie Jackson