For many proud Scots, the dream of a new world order was not really born in the reading room of the British Museum, as Karl Marx toiled away in the 1850s, but in a Clydeside mill town almost half a century earlier.

It was in New Lanark, in the early days of the 19th century, that Robert Owen laid out his vision of a new type of industrial community, one in which the labour of men and women would, for the first time in Britain, be valued and respected. Child labour was ended, a sickness fund established and an education provided.

It caused a storm among Owen's industrial and factory-owning contemporaries, but the story of New Lanark became one of the most glorious chapters in Scotland's economic history. More than two centuries later, another tempest is brewing here, involving the vexed relationships between industry and heritage and beauty.

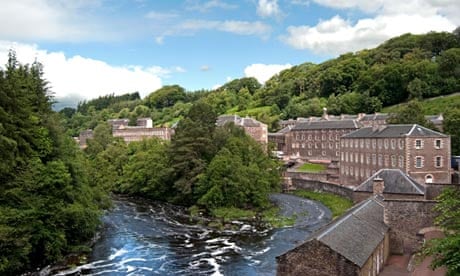

New Lanark has changed little since Owen's ideas changed the world. There is a stark splendour in these former industrial buildings, enhanced by their setting near elegant woods and tumbling water. Happily, the wretched tyranny of chrome and pine that must define, it seems, all modern "heritage" centres is absent here. In 2001, Unesco granted New Lanark world heritage status, one of only four sites on the Scottish mainland to receive this international kitemark. In recent months, though, thousands of local people and tourists have signed a petition in which they record their fear that this hard-won mark of global excellence may soon be withdrawn.

Cemex, a multinational minerals firm wants to extend its opencast quarrying operation nearby. How near is the subject of an increasingly noisy and aggressive debate that is beginning to engulf South Lanarkshire council, the Scottish government and Historic Scotland, the national agency tasked with the responsibility of maintaining the integrity of the site.

Cemex's application to increase its quarrying in the area is with a harassed local council. It is Historic Scotland, though, that is feeling the heat in this dispute. For reasons that it has failed to make entirely clear, it did not oppose the application by Cemex, stating: "Our view is that the proposal does not raise issues of national significance for the historic environment, and we have not, therefore, objected to the application. New Lanark is 1.5 miles from the nearest point of the proposed extension. It is clear there would be no visual impact from the quarry extension on any part of the village."

Local campaigners – backed by their MSP, Joan McAlpine – disagree. If the Cemex application were to be given the green light by the council, then 3.6 million tonnes of sand and gravel would be disembowelled from the Falls of Clyde landscape over the next six years. Campaigners feel that such a deep-rooted despoliation of the natural topography will leave such a huge scar, visible for miles, and that the integrity of the protective buffer zone and "designed landscape" will be violated.

McAlpine, a member of the SNP, recently won all-party support for a motion criticising the failure of Historic Scotland to oppose the Cemex application. Last night she said: "I sincerely hope that South Lanarkshire Council rejects this proposal. We are proud of New Lanark's world heritage designation and there is no doubt in my mind that a further six years of extensive opencast quarrying in the area puts this at risk."

It is not difficult to feel some sympathy for Historic Scotland, which may feel it is not just caught between a rock and a hard place, but about to be crushed by them. It points out that it weighed up several factors and that it is not its job to oppose industrial development for the sake of it. Its staff may have beards, it seems, but they do not have ponytails.

New Lanark had emerged in 1785, 14 years before Owen took ownership, as a purpose-built industrial village powered by the natural energy of the Falls of Clyde that comprised the 80ft Corra Linn and her three little sisters. Its planners, Richard Arkwright and David Dale, knew that harnessing the natural energy of four waterfalls in such close proximity could power not merely cotton mills in homes but entire factories of them.

When Owen took ownership, having married Dale's daughter, the village was already demonstrating an enlightened approach to industrial relations. Owen refined this further, codified it and made it the basis of his industrial philosophy.

There was a crucial relationship between business efficiency and healthy, valued workers, Owen found. Nevertheless, such radical ideas would take another 100 years or so to catch on. Owen would put an end to child labour and provide his workers with free medical care, high quality schooling, a workers' sickness fund and street lighting. Amid such practices profits flourished.

The value of the company grew from £60,000 in 1799 to £114,000 in 1813 – nearly £7m in today's money. The value to the nation, though, was even greater. The stubborn resistance of factory owners to treating workers like human beings might have taken a century to crumble, but common sense and humanity prevailed.

The extended quarrying will be visible from around the site of Corra Linn waterfall a few kilometres above New Lanark. This is where the river Clyde is at its most beautiful and innocent, before it is rudely importuned by Glasgow. When William Wordsworth visited in 1802 with his sister Dorothy and Samuel Coleridge, he called it simply "the Clyde's most majestic daughter". The mere thought alone of the earth being eviscerated anywhere in its vicinity seems environmental and cultural sacrilege, even if you can't see or hear it.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion