From the moment last year when The Argonauts, Maggie Nelson’s most recent book, was published in her native US, it was much talked-about, fervently recommended, highly fashionable. A blend of autobiographical writing, comment and quotation, it is about many things, one of which is love. The book tells how Nelson, after years of painful solitude, begins a joyful relationship with the artist Harry Dodge – she is amazed to come to terms with “the nearly exploding fact that I’ve so obviously gotten everything I’d ever wanted, everything there was to get. Handsome, brilliant, quick-witted, articulate, forceful, you.”

She relates how she and Dodge have great sex (“was his sexual power, which I already felt to be immense, a kind of spell I’d fallen under…?”), move in together and get married. Setting up home, they aren’t just a couple but a family: with them is Dodge’s three-year-old son from a previous relationship. Nelson, once dismissive of “breeders”, suddenly becomes an adoring step-parent, folding a young child’s tiny clothes. It soon emerges that this is a tale of more than one love. The book charts Nelson’s pregnancy, the birth of her son Iggy, and her first experiences as a mother: “It isn’t like a love affair. It is a love affair,” she writes of her and Iggy. “Or rather, it is romantic, erotic and consuming … I have my baby, and my baby has me.”

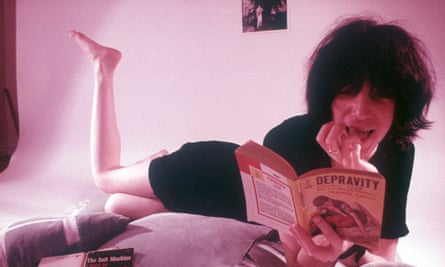

Nelson is candid, funny and – for many years a poet – has a talent for compression and juxtaposition that makes for an enthralling use of language. But this isn’t the only reason The Argonauts, now out in the UK, became a bestseller and has made such an impact. Nelson’s family is no ordinary family, whatever that might mean. During the first weeks with Dodge, despite them having spent “every free moment in bed together”, she is unsure what pronoun to use for her lover: he or she? To find the answer, a friend Googles Harry – who was born female, and at one point took the name Harriet Dodge – on her behalf. Dodge is fluidly gendered, but passes as a male – at least until the inevitable awkward moments when he shows his driver’s licence or credit card.

During the summer of 2011, as Nelson’s body is changing with her pregnancy, Dodge’s body is altering too – after years of being unable to live in his skin, with neck and back “pulsing with pain” from breast-binding, he injects testosterone and eventually undergoes “top surgery” (a double mastectomy). The couple have an apparently conventional domestic set-up, “flush with joy in our house on the hill”, and on the street or in restaurants they are often treated as a “normal” heterosexual family – man, pregnant woman, young child. Nelson interrogates how this feels, but is more interested in redefining what a family might mean. The Argonauts wants to untie the knots that limit the way we talk about gender and the institutions of marriage and childbirth.

“It’s been a big year for issues of sexuality,” Nelson says, when we meet at her home in the Highland Park neighbourhood of Los Angeles. She is referring in part to what has been called a “transgender moment”, with trans people more prominent than ever before (on TV, on the covers of high-profile magazines). So The Argonauts presents a series of very timely challenges – to binary or fixed ideas of sexuality, as well as to the many cliches surrounding pregnancy and early motherhood. (In fact, the book is a challenge to categorical ways of thinking about most things, and to prescription per se: Nelson embraces ambivalence.)

“I like to think that what literature can do that op-ed pieces and other communications don’t do is describe felt experience,” she tells me, “the flickering, bewildered places that people actually inhabit. I hope my book has made a nuanced contribution to a conversation that is important but can be too clearly delineated.” She mentions that among her readers are people who don’t get it, and who “write to me to let me know that, in case I missed it, there are only two genders, and anything else I might think is wrong. I want to write back and say: thank you so much for this news! Thanks for clearing that up for me!”

The Argonauts is full of telling autobiographical episodes, including Nelson being saluted by a member of the uniformed services simply for being pregnant (“the seduction of normalcy”). Its form, however, is far from that of typical life-writing. Not only is the chronology fractured, but the short, meticulously assembled, passages (“I’m not a good shoot-from-the-hip kind of person,” she says) include excerpts of theory – from the writings of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Judith Butler, Donald Winnicott and more.

“As I always do, I gave myself permission to be esoteric and complicated,” she reflects. “It was not a book in which I dumbed down or shaved the edges off, which is why its so-called success has been great, because I’ve always believed that people read much more challenging things than they are given credit for.” Her book has just won the National Book Critics Circle award for criticism.

In fact, Nelson describes The Argonauts as “a long tribute to the many feminist heroes that I had as teachers, men as well as women” (among them Sedgwick, Eileen Myles, Wayne Koestenbaum); “I call them ‘the many gendered mothers of my heart’.” As a student and young writer, she was “forged in the fire” of feminist and queer theory. (She has harsh words for such thinkers as Slavoj Žižek and Jean Baudrillard, who are unenlightened on issues of gender: they are men “pontificating from the podium”, the “voices that pass for radicality in our times”.)

The Argonauts documents the pleasures of a life “ablaze with care”, but is also streaked with darker colours – experiences without which, as Nelson says, happiness would not be so “visible and real”. Towards the end, a moving account of being in labour with Iggy is interleaved with beautiful paragraphs written by Dodge about tending to his mother during her final days dying of cancer. And there are other moments of “anxiety and dread”; for a short while, Iggy is even stricken by a rare and potentially fatal illness.

Nelson has said she deliberately “violates her privacy” in her writing (“People often ask me: do I feel it’s OK to put details of my private life in public? But there’s no genteel questioning, ‘should I or shouldn’t I?’”). We know a lot about her from the books, in particular the shadow cast over her family by the brutal murder of her aunt in 1969. She has scrutinised her childhood anxieties, her drinking and turn to sobriety, her beloved father’s death from a heart attack when she was 10, her liking of porn and interest in anal sex, her trip to the hospital with a junkie boyfriend who had overdosed, her past tendency to put herself “in fucked-up situations”, and so on.

In The Argonauts, she writes that Dodge, a more private person, “has told me more than once that being with me is like an epileptic with a pacemaker being married to a strobe-light artist”.

“Writing has been my main love for my whole life,” Nelson says. She tells a story in The Red Parts – her 2007 book which is about to be reissued by Graywolf Press in the US – about going, aged eight or nine, to her father’s office “perched atop a glorious skyscraper in downtown San Francisco”. Once up there, “he would give me a legal pad and a pen … My job was to write down everything that happened in the room – my father’s hectic pacing, his wild gesticulations on the phone, visits from fellow lawyers … the view of the slate-gray harbour below.” Ever since, she says, recounting the tale, she has been “scribing … paying attention to everything going on around me”.

Nelson was born in 1973 and grew up in the Bay Area, though “I had many households because my parents divorced and lived in many different places”. She has always been “hard” on her mother in her writing, she admits, not least the fact of her leaving her father for another man a couple of years before her dad’s death at the age of 40. Nelson’s older sister, Emily, ran wild, having an abortion in her early teens, dropping acid, watching snuff films, stealing their mother’s car. In large part, Maggie “got good grades and flew under the radar”, but she had panic attacks about death and dying, and as a teenager she “liked to take baths in the dark with coins placed over my eyes”.

Aged 12, she was delighted to win a poetry contest held under the auspices of her favourite band the Cure: hers was “a terrible poem”, a crude imitation of the lyrics on their album The Top, but her words were reprinted in a black pamphlet sent to her, and it was “an incredible thought” that someone had picked out what she written. “I read that Robert Smith loved Earl Grey tea and the novels of Patrick White, so I went through a phase of drinking Earl Grey tea and reading Patrick White. In Haight Ashbury. It was a strange moment.”

Having visited New York a couple of times as a teenager, Nelson’s “needle pointed that way”. She left home, aged 17, to attend Wesleyan University in Connecticut, an hour and a half outside of the city. There, she was taught writing by the Pulitzer prize-winning Annie Dillard, and encountered for the first time the “charismatic and outspoken” Eileen Myles, who in 1991 – in an act that was part performance stunt, part protest – was running for president as the first “openly female” (also openly gay) candidate; Nelson’s college was one of her campaign stops.

Afterwards, Nelson has written, “I literally moved to NYC to find [Myles’s] body, her voice, to be near whatever it was I saw and heard that night.” She attended many of the workshops that Myles ran from her home in the East Village, met “artists in all kinds of fields”, and considers this her equivalent of taking a fine arts master’s degree. She took countless jobs in bars and restaurants, and became part of an avant garde, DIY, punk poetry scene involving the small indie Soft Skull Press – and read poetry before rock shows (Patti Smith is another of Nelson’s heroes). “I wasn’t the kind of writer who was saying, oh if only the New Yorker would publish me,” she laughs. “Self-publishing wasn’t what you did because you were rejected by HarperCollins; it was what you did because it was fun to make zines and run around with them.”

In 1998 Nelson began a graduate course at the City University of New York. It was here that she began working on the project that would become her 2007 book Women, the New York School, and Other True Abstractions. She published books of poetry, but realised that poetry “was never the full container for what I wanted to do”. She also continued the eight years’ work that went into Jane: A Murder, published in 2005.

Her mother’s sister, Jane Mixer, was travelling home from the University of Michigan for spring break when she was killed: her body was found with two bullets in her brain and a stocking so tightly wound around her neck that her head was nearly severed. “We were born under the shadow of this very recent event in my mother’s life,” Nelson tells me. A year after it happened, her parents moved to California, “literally moving away from the scene of the crime”. The murder remained unsolved, though for many years it was “thought to be part of a serial killing spree called the Michigan murders, attributed to a guy called John Collins, who is still in prison”.

“There was a real sense of dread and unknowability around the story,” Nelson remembers. She decided to tackle the subject “as a writer and feminist and someone interested in not letting the striking down of this motivated, intelligent, civil-rights-oriented person go down in repressed family history.” She unearthed Jane’s journals, and conducted innumerable hours of research in order to write what was to become a collage of poetry, prose and documentary sources – words designed to “disrupt the tabloid, ‘page-turner’ quality of the story”. Nelson immersed herself so deeply that she began to be afflicted by what she called “murder mind”: “I could work all day on my project with a certain distance, blithely looking up ‘bullet’ or ‘skull’ in my rhyming dictionary. But in bed at night I found a smattering of sickening images of violent acts ready and waiting for me.”

Just as Jane was about to be published, late in 2004, Nelson, incredibly, “got a call from Michigan state police saying they had a DNA match in the case, after 36 years, and that they were going to bring a new suspect to trial”. She was exhausted by it all but, when the trial was announced, “it seemed too strange not to go”. So Nelson – now an expert on the case, consulted by the homicide detective – attended every day with her mother, endured a gruesome few months, and wrote The Red Parts. The book is subtitled “Autobiography of a Trial”, and she describes it now as “a pretty straightforward courtroom narrative interspersed with stories about my childhood”. The suspect was found guilty.

In 2005, she left New York for Los Angeles to take up a prized teaching job at the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts). This seems to have ushered in “the loneliest three years of my life”. An intense affair had recently ended; she was a jilted lover. “I found myself losing the man I loved,” she wrote in The Red Parts. “I was falling, or had fallen, out of a story, the story of a love I wanted very much … And the pain of the loss had deranged me.”

This pain is at the heart of what was Nelson’s best-known work until The Argonauts – the cult favourite Bluets (2009). Comprising 240 numbered paragraphs written between 2003 and 2006, the study started out as a meditation on colour and an exploration of the “staggering experience of aesthetic wonder”. Nelson had always collected blue things, and at one time hoped to travel to “famously blue places” – ancient woad production sites, Chartres cathedral, the lapis mines of Afghanistan and so on. But “then I had this breakup”, she says, and soon afterwards a close friend was left paralysed by an accident. “And I let those things permeate the book, so that it began to be about the relationship between pleasure and pain, and not just about beauty.”

But before Bluets even appeared, Nelson met Dodge – who is also on the faculty at CalArts – at her party to celebrate the publication of The Red Parts. She was sharing the stage with Myles, “and Eileen and Harry go back a long way”. Dodge lived most of his formative art years in San Francisco and ran a cafe and public space called Red Dora’s Bearded Lady. With Myles, he was involved with the spoken word and performance art collective Sister Spit; in 2001 he made the “queer buddy” film By Hook or By Crook, with Silas Howard (who is Iggy’s godfather, and a director on the TV show Transparent). “Harry was working the West Coast angle, while I was in New York … but it’s the same world.”

Their meeting was a moment of renewal. The title of The Argonauts comes from a Roland Barthes passage that compares a person saying “I love you” to one of the Argonauts who repairs and renews his ship during its voyage. Nelson recalls that, feeling vulnerable after having said “I love you” to Dodge at the beginning of their time together, she sent him the quote, which suggests that the “task of love and language” is “to give to one and the same phrase inflections which will be forever new”.

Near the beginning of the book, Nelson describes her and Dodge getting married hours before California revoked its legislation on gay marriage and began a (temporary) ban. “Poor marriage!”, she writes. “Off we went to kill it (unforgiveable). Or reinforce it (unforgiveable)” – their marriage is both subversive and the opposite of subversive. She examines different facets of this, and later remarks on the “assimilationist” bent of “the mainstream LGBTQ+ movement” that has rushed to seek entrance into “two historically repressive structures: marriage and the military”.

She tells me that Harry and her talk a lot at home about the hopefulness embedded in much queer theory that “there’s something about non-normative genders and sexualities” that encourages a politically radical tendency. “We don’t yet know how people would behave if we stopped incentivising marriage” financially and culturally, she says. But for the moment, “the tethering of politics to certain genders and sexualities has probably passed … The most shocking thing about Caitlyn Jenner is that she’s a Republican. That’s proof alone that it’s not clear what politics stem from certain gender and sexuality arrangements.”

Before meeting Dodge, Nelson was suspicious of the whole idea of family – “for all the familiar feminist, queer, and collectivity-based” reasons. But Harry, she has said, used the term “so widely and happily. It really amazed me.” When the two got married, it was, we learn in The Argonauts, in a temporary chapel room, with a drag queen at the door who “did triple duty as a greeter, bouncer, and witness”. Officiating was Reverend Lorelei Starbuck, who listed her denomination as “Metaphysical” on the forms. The ceremony was rushed, and in some ways deeply unserious, but the couple didn’t account for love: “as we said our vows, we were undone. We wept, besotted with our luck.” Then they went to pick up Dodge’s son, “came home and ate chocolate pudding all together in sleeping bags on the porch, looking out over the mountain”.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion