In 1907 the Art Journal told its readers: "There must be few people in London interested in art who do not know the name Austin Osman Spare." Within a few years they would have done better to ask if there was anyone out there who did know his name, because Austin Spare had his career the wrong way round: he began as a controversial West End celebrity and went on to obscurity in a south London basement. Since his death in 1956 he has been simultaneously forgotten and celebrated; a minor cult figure, collected by rock stars (Jimmy Page of Led Zeppelin has a Spare collection) who has only recently become the subject of wider interest.

Born in Smithfield in 1886, the son of a policeman, Spare was something of an enfant terrible on the Edwardian art scene, where he was hailed as the next Aubrey Beardsley. He experimented with automatic drawing some years before the surrealists, went on to work as an illustrator and war artist, and edited the journals Form and the Golden Hind. Not everyone liked his work, and George Bernard Shaw is alleged to have said "Spare's medicine is too strong for the average man." Too strong or not, the odds were already stacked against him by the hidden injuries of class; lacking in education and the social skills to get on in the metropolitan art world, Spare's career foundered in the early 1920s and he fell back into working-class life south of the river, living in a Borough tenement block as – in his own words – a "swine with swine."

"If you're ever passing my place, do drop in," Spare said to Clifford Bax, a more privileged friend from his editing days, but Bax reflected sadly that no one ever would be passing Borough unless they were unfortunate enough to live there. Increasingly reclusive, living outside of consensus reality, Spare spent the 20s voyaging into automatic and "psychic" drawing, only to find a new identity thrust on him in the 30s as Britain's first surrealist ("FATHER OF SURREALISM – HE'S A COCKNEY!" ran a 1936 newspaper headline). This didn't mean he was hanging out with Salvador Dalí and André Breton; instead he was trying to sell his "Surrealist Horse Racing Forecast Cards" through a small ad in the Exchange and Mart.

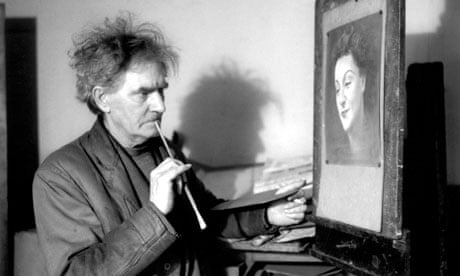

At this time based in a studio above the Elephant and Castle Woolworth's, Spare was producing exquisite stylisations of film stars such as Jean Harlow and Mary Pickford, using a technique of altered perspective that he called "siderealism", Pan-like "satyrisations" of male faces, and pastel portraits of local cockneys, particularly old women. One of the stranger Spare stories of the period involves a request from Hitler for a portrait, seemingly through a member of the German embassy staff; Spare refused, and briefly became a hero in the local papers.

Blitzed in the war, he ended up in a Brixton basement – dark, foul-smelling, and too small to stand back from work in progress to see it properly – looking after a horde of stray cats. The postwar London landscape was very distinctive, with cats proliferating in the ruins, wild plants springing up on bomb sites, and live pianists in public houses, where Spare spent much of his time: the Harry Lime theme from the film The Third Man was popular, and a friend remembered it as "almost Spare's signature tune". He never gave up. Needing to survive outside the gallery system, shortly after the war he hit on the idea of holding shows in South London pubs.

It is a commonplace to say that this or that figure lived from the era of the horse and cart to the first jet planes, conveniently forgetting that the same is true of millions of other people from the same generation, but Spare really did inhabit his times in a quite distinctive way, living from the dog-end of the Beardsley era, keeping on with the Edwardian cult of Pan in his satyr-pictures, then embracing the heyday of Hollywood Babylon and the social changes beyond; one of his postwar pub portraits is called Docker with National Teeth – NHS dentures were still a novelty at the time.

Spare's art has an equally broad spread; the most striking thing about it is the chameleonic range of styles, from carefully finished pastel portraits to figures emerging from rapidly scrawled calligraphy, unified only by the fact that he could really draw; it was Spare's misfortune to live through a century when drawing wasn't much valued, and he never came to terms with modern art. Spare's old-style draughtsmanship led to inflated comparisons with Dürer and Michelangelo and Rembrandt, often by people outside the art world who were surprised to find that "real art" was still being made. The difficulty of getting to grips with Spare's art on its own terms has led to similarly wild comparisons pointing forwards: not only was Spare credited as Britain's proto-surrealist in the 30s, but in the 60s the critic Mario Amaya (a pop art specialist, shot and wounded alongside Andy Warhol when Valerie Solanas attempted to assassinate him) saw him as Britain's first pop artist.

Spare might not be the first surrealist or the first pop artist, but some of his work is weirdly, irreducibly original. His attempts to "visualise sensation" with fleshly, ugly-bugly figures around 1910 are unlike anything else in Edwardian art, and his self-portraits "as" others in the 20s and 30s – as Hitler, as Christ, and as a woman – look forward to the work of Cindy Sherman and the Japanese artist Yasumasa Morimura, who has depicted himself as Chairman Mao, Hitler, and a Pre-Rapahalite maiden. Spare's sexually graphic self-as-woman pictures couldn't legally be displayed in their day, and they were quietly owned by EM Forster.

However notable some of Spare's art might be, his memory has been kept alive for many years more by cultists than art lovers. He was influenced by the supernatural currents of his early youth, including theosophy and spiritualism, and he was briefly an associate of Aleister Crowley, the self-styled Beast 666, before they fell out. Spare's innovative approach to magic was a brilliantly self-educated attempt to manipulate his own unconscious, giving his wishes the demonic power of complexes and neuroses and nurturing them into psychic entities, like the old-style idea of familiar spirits. How successful this was in merely mundane and worldly terms can be judged from the fact that a magazine article of the 40s could treat Spare as a human-interest story about a starving artist; a woman in South Africa posted him a tin of pineapple after reading it, and closer to home someone in Streatham sent him some tinned salmon.

It was this same article that brought Spare to the attention of Steffi and Kenneth Grant, and it was in the writings of the late Kenneth Grant, who died this January, that Spare was reinvented as a dark sorcerer, seduced and initiated in childhood by an elderly witch in Kennington. Grant preserved and magnified Spare's own tendency to confabulation, giving him the starring role in stories further influenced by Grant's own reading of visionary and pulp writers such as Arthur Machen, HP Lovecaft, and Fu Manchu creator Sax Rohmer. Grant's Spare seems to inhabit a parallel London; a city with an alchemist in Islington, a mysterious Chinese dream-control cult in Stockwell, and a small shop with a labyrinthine basement complex, its grottoes decorated by Spare, where a magical lodge holds meetings. This shop – then a furrier, now an Islamic bookshop, near Baker Street – really existed, and part of the fascination of Grant's version of Spare's London is its misty overlap with reality.

Anyone old enough to remember watching ITV in the early 1970s, with Benny Hill and On the Buses, has probably seen a Spare picture without knowing it: a sinister satyr face flashed up on screen in an advert for the "Buy part one, get part two free" magazine, Man Myth and Magic (available every Thursday from your newsagent at four shillings) with which Grant was involved. He had also made a doubly arcane appearance on late 60s psychedelic vinyl when a little-known band called Bulldog Breed (not to be confused with any later bands of the same name) recorded a track about him.

Since then Spare has been taken up by graphic novelists and experimental musicians, and it looks as if his art is finally gaining wider recognition outside the occult ghetto. A Spare exhibition late last year at the Cuming Museum in south London was so popular – helped by a piece on the BBC's Culture Show – that timed admission had to be introduced, and there is a further documentary in the offing later this year. The serious recognition that largely eluded him in life seems to be coming at last. At the very least, he deserves to be recognised as part of what Peter Ackroyd has described as the "Cockney visionary tradition". In the words of one of his obituaries ("Strange and Gentle Genius Dies" in the Evening News), "You have probably never heard of Austin Osman Spare. But his should have been a famous name."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion