San Diego Cityscape: Who is Norman Foster, the man set to transform the San Diego Museum of Art?

Balboa Park began more than 100 years ago with architect Bertram Goodhue’s vision of a dream city of gorgeous Spanish Colonial buildings and lush gardens, where visitors would stroll along open promenades and under shady arcades. After the 1915-16 Panama-California Exposition, he imagined, most buildings including his own would be razed and “San Diego would enter upon the heritage that is rightfully hers.”

And yet. San Diegans clung tenaciously to the dream. Original buildings still stood. Crumbling structures like the House of Hospitality and House of Charm received expensive re-creations in the 1990s. Many new buildings were added.

Today, Goodhue’s original Spanish impulses, also reflected in 1935 expo architecture directed by Richard Requa, remain prevalent at the heart of the park, where the San Diego Museum of Art earlier this month announced a major expansion.

SDMA selected superstar British architect Norman Foster’s company Foster + Partners to replace its West Wing, with construction due to begin in 2026. The new building will include an education center, a public pavilion, restaurants and a rooftop space with views of the park.

The announcement produced all sorts of reactions, from enthusiastic support to heated opposition and somewhere in between. Foster’s buildings range from radical to subtler, but the electricity is palpable. It must be said that passionate debate is a good thing and often leads to better buildings.

I am a fan of contemporary architecture. I have no issue with adding something different to Balboa Park, even if older buildings are lost or modified. A thoughtful new design can sit comfortably amid older ancestors. History is about change, and more variety creates richer experiences for visitors. But I wonder whether Foster’s bold high-tech brand of architecture can be finessed into the century-old fabric of San Diego’s favorite historical place.

Norman Foster’s legacy

Foster is known for major projects in Navi Mumbai (a planned city of 2.6 million on India’s West Coast), Shanghai, Sydney, Japan, China and Dubai, among other locales. Of course, they are prolific in Foster’s native UK, where his most famous project is a 591-foot London high-rise wrapped in spirals of glass and known as The Gherkin — if you are unfamiliar with the building, you can guess how it earned its nickname.

In California, Foster designed Apple’s huge circular headquarters in Cupertino, inspired by Steve Jobs’ obsession to build a sustainable corporate campus with innovative architecture and spectacular outdoor spaces. It’s as distinctive as an iPhone or a MacBook, but with little of the understated elegance.

Foster is also the primary architect behind One Beverly, a gargantuan $2 billion mixed-use project proposed for downtown Los Angeles that raises questions about scale, context and density.

According to SDMA’s Director and CEO Roxana Velásquez, Foster was selected in large part for its thoughtful expansions of historical museums.

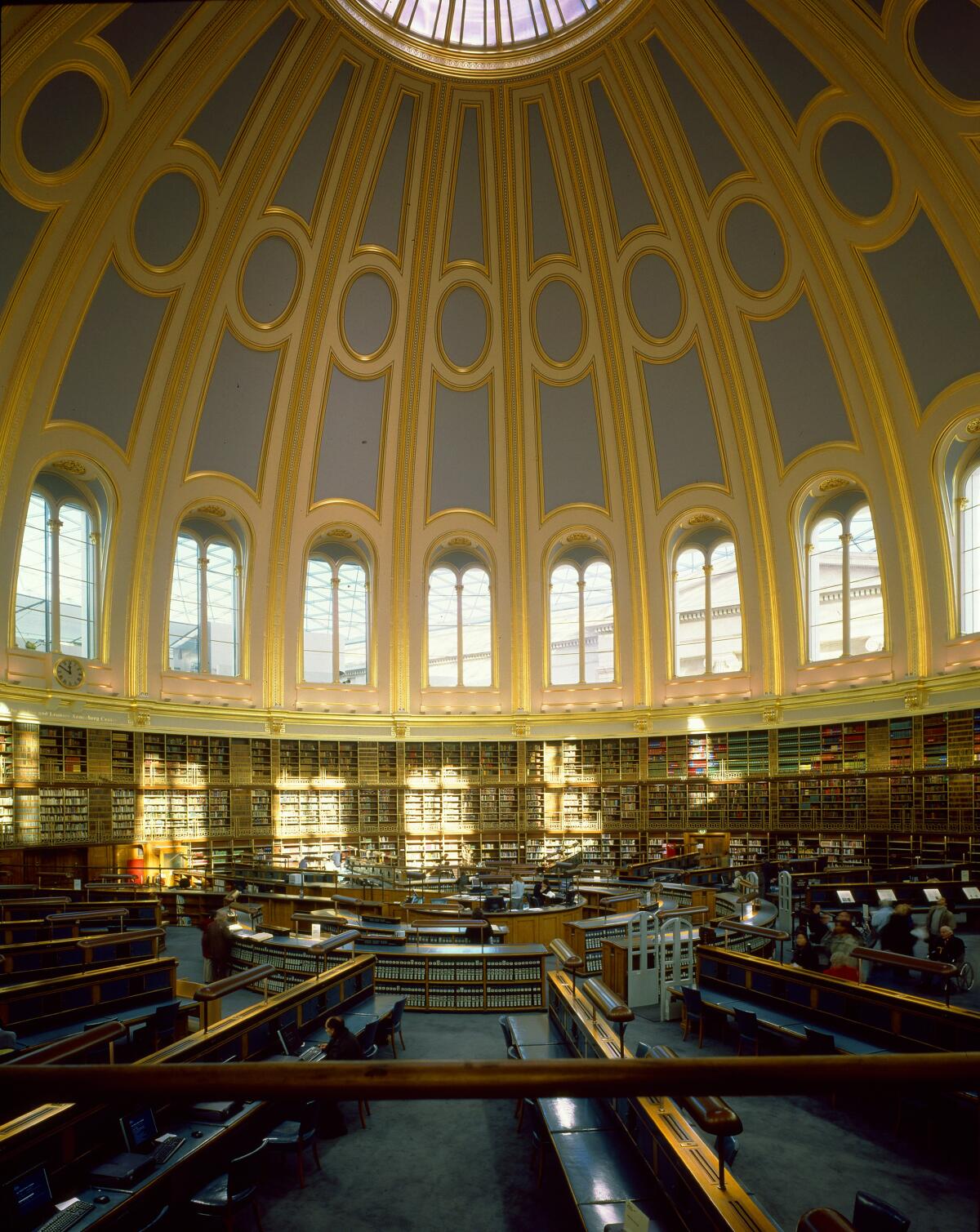

Among them is an addition to the Elizabethan Great Court at the British Museum in London, completed in 2000. The building spans two acres and is covered with a glass roof atop a central stalk.

“With its mix of architecture and urban design, and its confrontation of classicism with computer-generated design, the British Museum’s Great Court is one of the defining buildings of Norman Foster’s career,” said the UK Guardian’s critic.

At the Museo del Prado in Madrid, Foster is adding a substantial building with new galleries and public spaces, inserted with care among its 17th, 18th and 19th-century neighbors. The light and graceful design complements the historical architecture, and the inviting outdoor spaces include a central pedestrian promenade sheltered by a thin slab supported by tall narrow columns.

In northern Spain, Foster has designed an extension described as a “floating pavilion” for the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum, with a swooping rooftop structure including galleries and viewing platforms — an idea that may reappear at SDMA.

The lay of the land

Meanwhile, stand back from the museum, at the edge of the circular Plaza de Panama, and take in a visual spectacle quite different from the stark white modern buildings originally proposed by Irving Gill. San Diego’s most famous architect in the early 1900s was swept aside in favor of Goodhue by city fathers promoting the expo.

Pedestrians arrive at the plaza via the park’s signature covered arcades. The plaza itself is a jumble of pedestrians and cars due for a makeover (Foster’s team is already thinking about it).

To your left, along the Prado, is a reconstructed remnant of the original Science and Education Building. It’s the only sign of that ornate Spanish Colonial structure. It was torn down in 1964 and replaced with Architects Mosher Drew’s single-story, 35,000-square-foot SDMA West Wing, which now includes galleries, an auditorium, the outdoor Panama 66 café and the adjacent sculpture garden.

An arch in the remnant leads to an arcade that heads west past Goodhue’s California Building, with its signature tower and tiled dome, and his Museum of Man (now the Museum of Us). In the distance is Frank P. Allen’s arched Cabrillo Bridge, which carries visitors into the park from Laurel Street.

To your right in the distance is Carleton Monroe Winslow’s Botanical Building (1915), now undergoing major restoration. In the foreground is San Diego architect Frank L. Hope’s recently renovated Timken Museum (1965), an unlikely modern box amid the Spanish spectacle.

There in front of you stands the historical SDMA building (1925) by San Diego architect William Templeton Johnson, with rich plaster decoration that includes statues of Spanish painters, Michelangelo’s David, shields of Spain and San Diego, along with cherubs and a large seashell crowning the main entry.

It has a magnetic pull for visitors who see it in the distance as they approach from the Spreckels Organ Pavilion and pass between the House of Hospitality, which includes the Prado restaurant, and the House of Charm, which contains the Mingei International Museum — two buildings straight out of Spanish romance.

Foster’s addition is “desperately” needed, according to Velásquez. Since her arrival in 2010, after heading museums in Mexico City, the SDMA collection has expanded by more than 5,000 pieces, while attendance has increased fivefold.

Praise and concerns

The announcement of Foster’s hiring has already received wide coverage rarely accorded to San Diego architecture.

Meanwhile, preservationists who treasure historical architecture, along with fans of buildings by architect Robert Mosher, are mustering forces. Velasquez said it is likely Foster’s addition will replace all of Mosher’s wing including the café, although loading docks might remain. The front part of the wing is a dated bunker, but I can imagine that Foster might in some way incorporate Mosher’s elegant café area, with its spare fluted columns.

Modern architecture from the 1960s, such as Mosher’s, is reaching “historical” status and has a large following. Mosher’s best-known designs include the Coronado Bridge, as well as planning and architecture for UC San Diego’s Muir College.

Despite protests, Mosher’s addition to the La Jolla location of the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego was demolished to make way for a 1990s addition by Robert Venturi and Denise Scott-Brown — which in turn was replaced with a recent expansion by New York architect Annabelle Selldorf. Selldorf was praised for re-creating Gill’s original 1916 building as the building’s central feature.

Back in Balboa Park, what do San Diego’s architectural leaders think about Foster in San Diego? Many architects I spoke with seem jazzed about the addition and what it could do for San Diego’s status in the world of architecture.

“Hiring Foster + Partners is terrific for this project,” said architect Kevin deFreitas, president of the San Diego chapter of the American Institute of Architects, in a statement on behalf of AIA that did not mention the existing Mosher building.

DeFrietas’s peers in San Diego historical preservation take issue with that view.

Bruce Coons, executive director of the Save Our Heritage Organisation (SOHO), said in an email: “SOHO maintains that it is essential that the replacement of the current buildings at the San Diego Museum of Art include the reconstruction of the facades and towers of the spectacular Science and Education Building.”

Balboa Park’s Committee of 100, longtime guardians of the park’s historical architecture, doubled down on these sentiments.

“C100 advocates for all new designs to adhere to the historic architectural context of the Spanish Colonial style, as called for in city policy, the 1989 master plan and the 1992 precise plan,” said Committee president Ross Porter, in an email.

Nonetheless, both preservation group leaders said they look forward to working with the architects towards a suitable design. Velásquez promises an engaging design process that will welcome input from design experts as well as the general public.

Maybe there’s an opportunity for a cooperative effort that could refine the architecture and engage the community even before construction begins?

The selection process

Foster + Partners won the job following a lengthy process that began with a field of 60 architects from around the world. The list was closely vetted by Velásquez, and top SDMA staff and curators, along with an ad hoc committee including experts in architecture, design and planning.

Five finalists were invited to San Diego to make presentations that included models and sketches. I would love to see them, but at this point the project is tightly controlled and Velásquez said they would not be released. No photography was allowed during the presentations.

Besides Foster, the finalists were Snøhetta of Norway; Diller Scofidio + Renfro of New York City; Olson Kundig of Seattle; and David Chipperfield of London. All have significant museum experience. San Diego architects were among the initial 60 and a Mexican architect made the final 10. Velásquez did not share the names of these runners-up.

At 87, Sir Norman Foster (he was knighted in 1990) has said he feels more energized and inspired than ever. But for this project, the titan of contemporary architecture will be involved mostly from a distance, if at all.

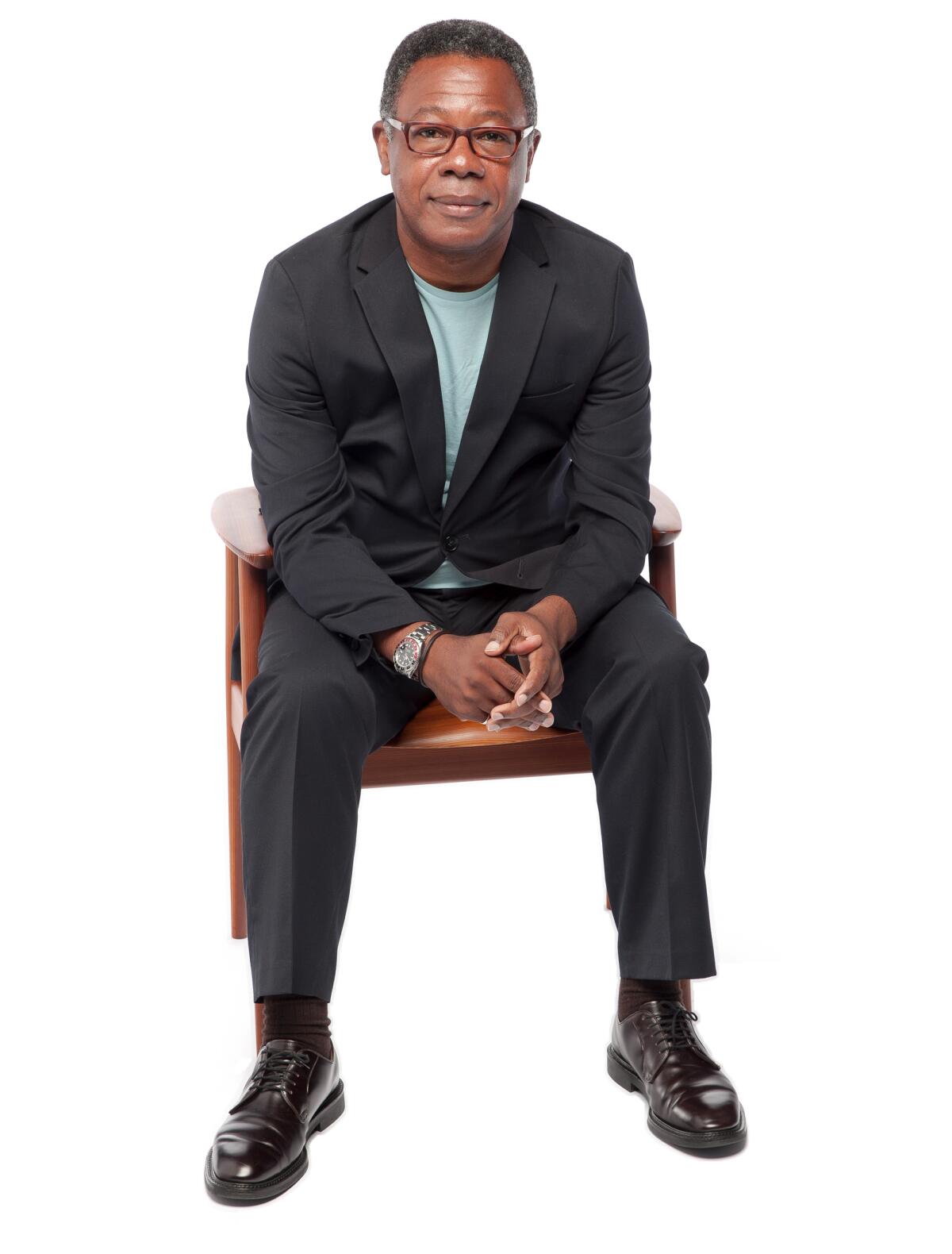

Leading the design team will be Nigeria-born architect Armstrong Yakubu, a partner at Foster since 1987. Yakubu was mentored by Foster at the Architectural Association School of Architecture in London and recruited by Foster upon graduation. The Foster team also includes an architect of record: LPA, which has a San Diego office. It also includes a landscape architect that Velásquez would not name. In California, Foster has previously collaborated with Los Angeles landscape architects RIOS as well as Philadelphia’s Olin Studio.

Yakubu was not made available for an interview, but a Norman Foster Foundation video of him on YouTube reveals a soft-spoken, thoughtful man, perhaps well-suited to managing the design challenges and conflicts ahead. In the video, he speaks highly of Foster and talks about his pride in their conversion of the Murray Building — a Hong Kong landmark — from offices to a hotel. It features a pedestrian-friendly base of tall arches, lush gardens and inviting plazas with shady places to sit.

“It’s arguable that the spaces between buildings are probably more important than the buildings themselves,” Yakubu said, along with another comment that may bode well for SDMA’s project: “Architects have the responsibility to preserve. I like to use a lot of R’s … renew, reinvent, re-establish, you know, re-use.”

Looking to the future

As inappropriate for Balboa Park as Foster’s architecture may seem to some, Velásquez is confident.

“We are conscious of being respectful of the plaza, not doing anything that will be disruptive, like (Los Angeles architect Frank) Gehry. I love Gehry, but this is not the place to have a Frank Gehry presence,” she said.

SDMA has yet to attach a price tag to its project. But for comparison’s sake: the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego’s recent expansion by Selldorf cost $105 million, and major renovation of Balboa Park’s Mingei International Museum by San Diego architect Jennifer Luce cost $55 million. SDMA’s budget is certain to far exceed those, but Foster’s presence will undoubtedly boost fundraising.

And in Balboa Park, the dream continues.

Unlike most dreams, Goodhue’s vision of a Spanish arcadia — in keeping with romantic visions of California as depicted in early-20th century fiction, tourism and Sunkist orange crate labels — did not fade away. Instead, Balboa Park has become an epic story of architecture, art, gardens and life in San Diego. It will be fascinating to see where this fever dream takes us next.

Sutro writes about architecture and design. He is the author of the guidebook “San Diego Architecture” as well as “University of California San Diego: An Architectural Guide.” He wrote a column about architecture for the San Diego edition of the Los Angeles Times back in the day and has also covered architecture for a variety of design publications.

Get U-T Arts & Culture on Thursdays

A San Diego insider’s look at what talented artists are bringing to the stage, screen, galleries and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.