Cracking the Universal Code of Beauty: Owen Jones's Grammar of Ornament

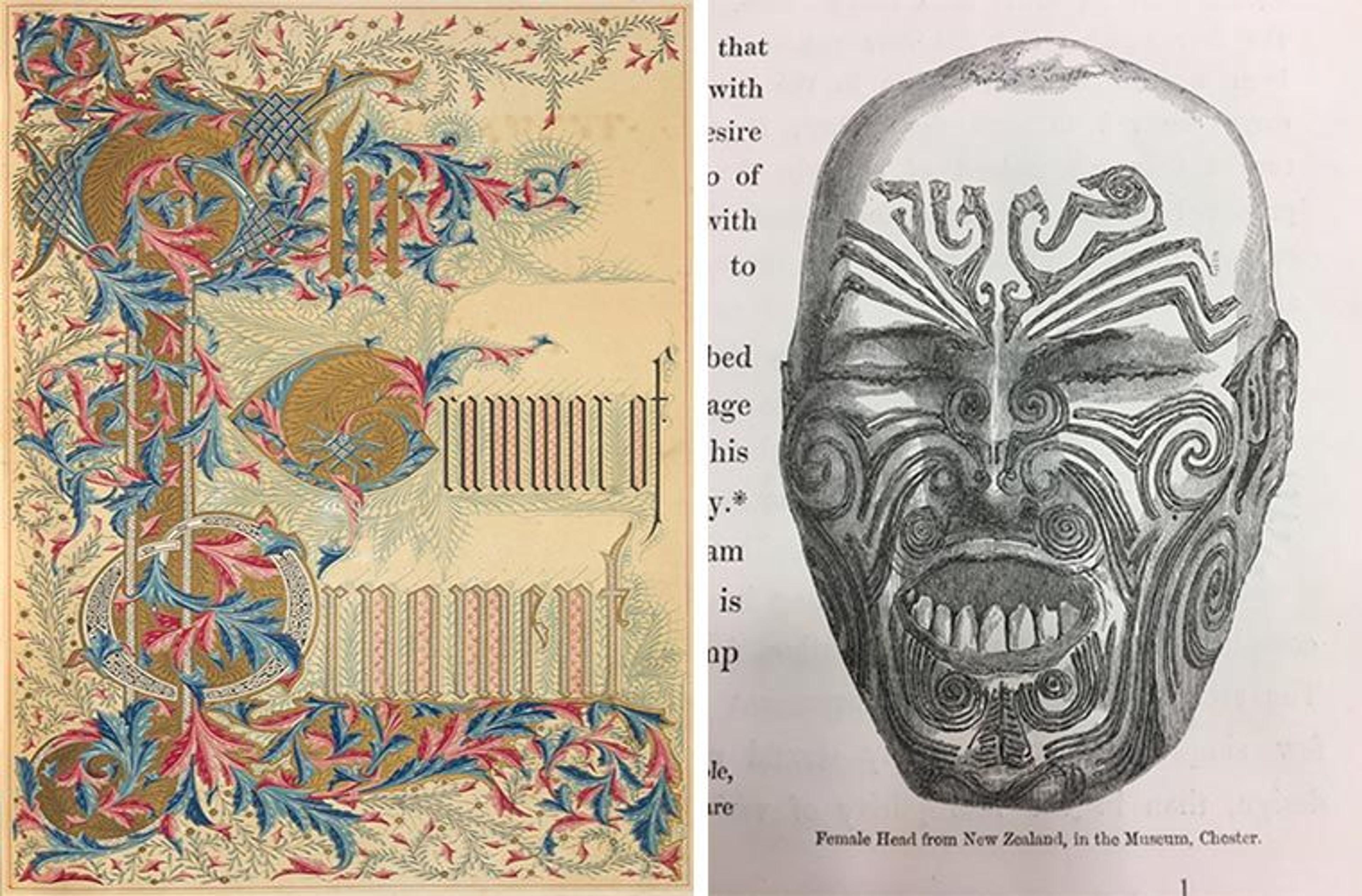

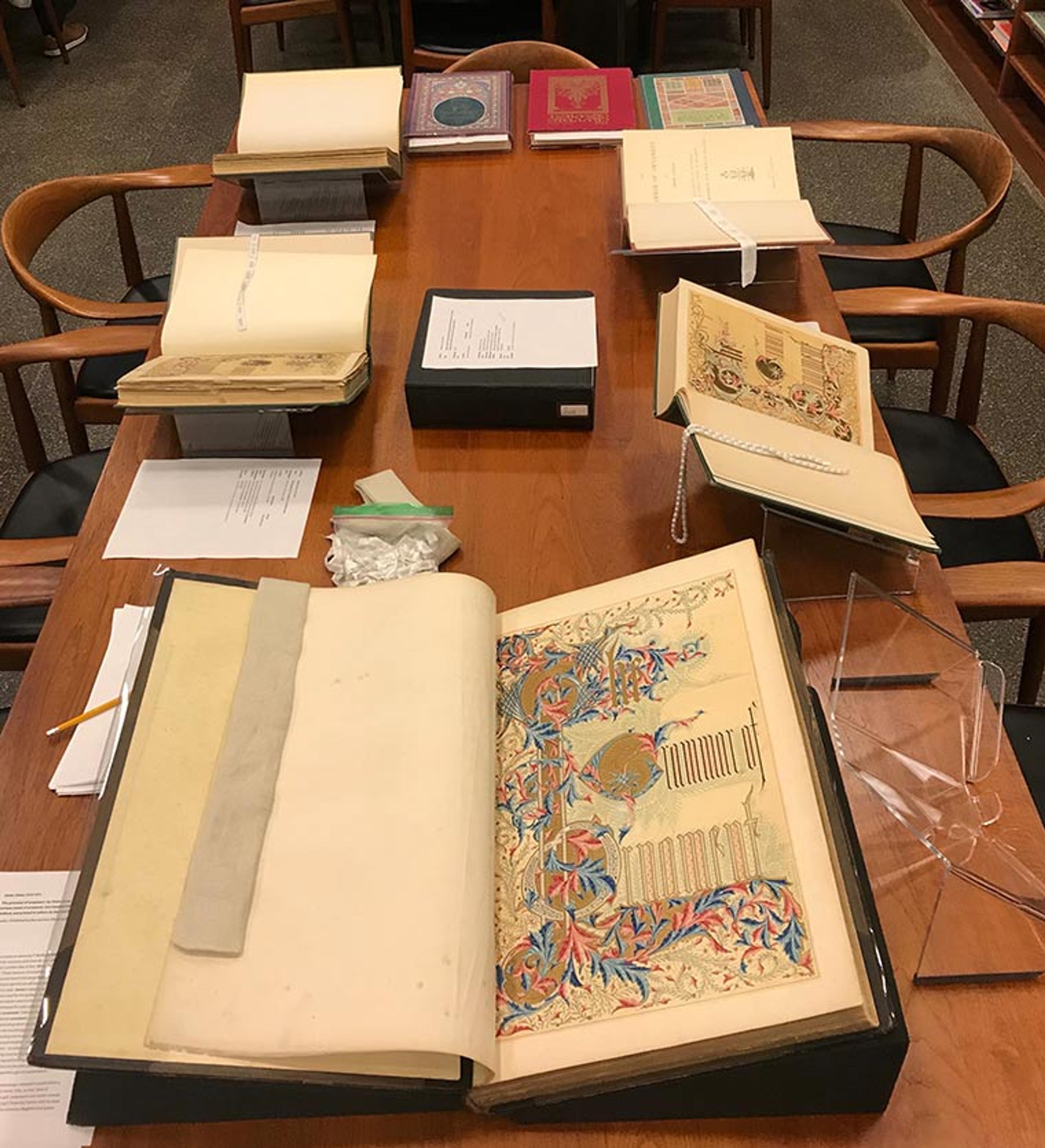

Owen Jones, The Grammar of Ornament (London: Day and Son, 1856). Left: title page. Right: close-up of the image on page one. All subsequent images are from Jones's book, except where noted.

Watson Library recently acquired an original folio edition of Owen Jones's (1809–1874) seminal work, The Grammar of Ornament, published in 1856. We had numerous copies of the quarto version and multiple later versions and reprints (it has never been out of print, which is a testament to its importance), but not the original. We were able to purchase this edition with funding provided by the Friends of Watson Library.

In the following paragraphs, Femke Speelberg, Associate Curator of Historic Ornament, Design, and Architecture in the Department of Drawings and Prints, helps illuminate why this is one of the great color plate books of the nineteenth century—and certainly one of the most influential.

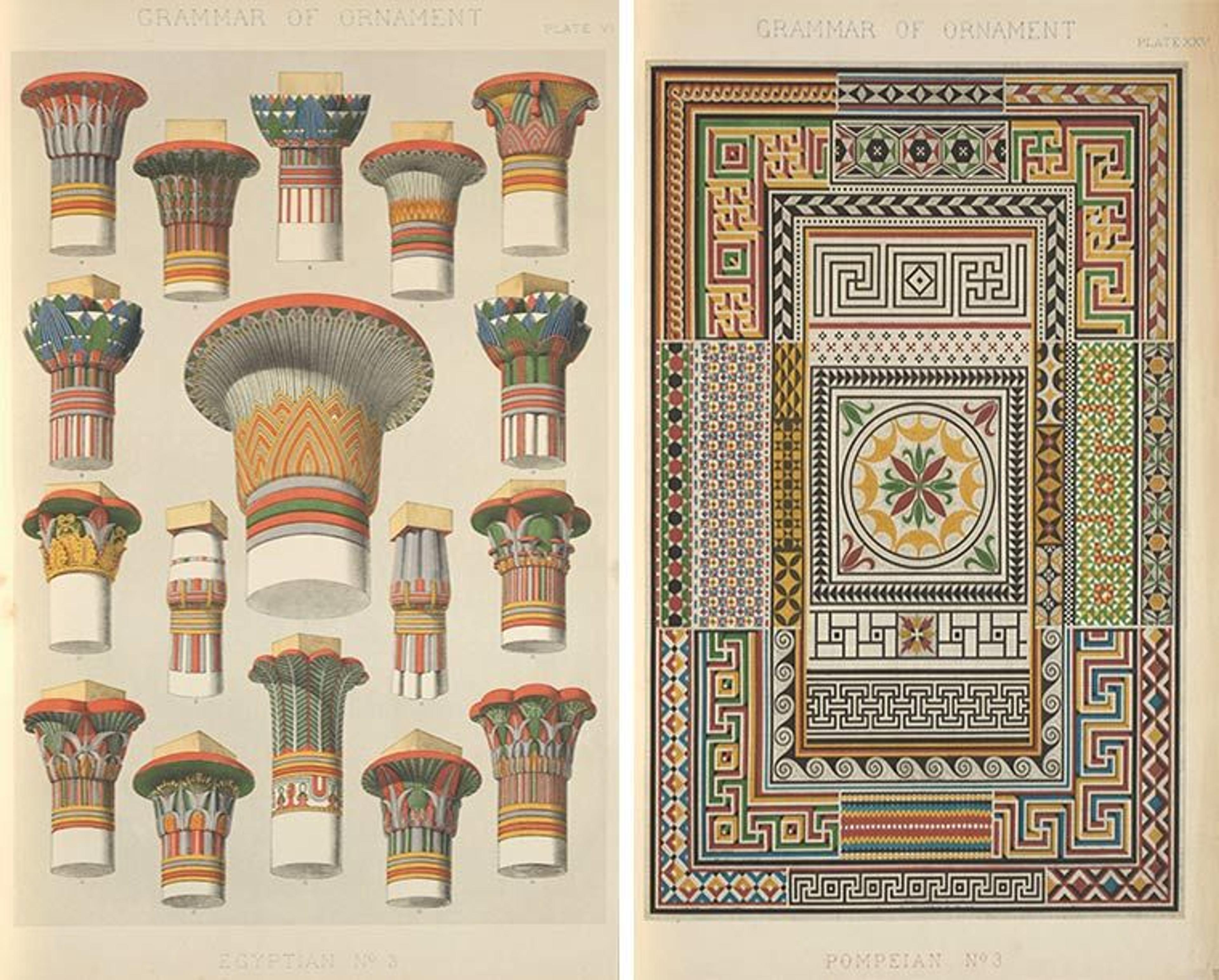

Left: Plate VI, Egyptian. Right: Plate XXV, Pompeian

From the universal testimony of travelers it would appear, that there is scarcely a people, in however early stage of civilisation, with whom the desire to ornament is not a strong instinct. Man's earliest ambition is to create . . . to stamp on this earth the impress of an individual mind.

In the opening chapter to his seminal work The Grammar of Ornament, Owen Jones stresses the fact that one of the universal qualities among humankind is the desire to make beautiful things. To illustrate this point, he uses the somewhat macabre example of a severed preserved head of a Maori warrior (mokomokai), then thought to be a woman, which was covered in an elegant pattern of facial tattoos. He admired it particularly for the harmonious way in which the responsible artist had married the tattooed lines with the natural shapes of the human face. Rather than concluding that ornament belongs purely to the primitive, as others would argue later, Jones realized through his confrontation with this ethnological specimen that the Maori possessed an innate understanding of beauty that was alien to modern Western society.

Jones, who was an architect by training and a prominent figure in the London art world, set out to reacquaint his colleagues with the underlying principles that made art beautiful. Instead of writing an academic treatise on the subject, he chose to assemble a book of one hundred plates illustrating objects and patterns from around the world and across time, from which these principles could be distilled. While Jones had traveled within Europe and to parts of the Middle East, many of his illustrations take advantage of the museological and private collections that were available to him in England, and the objects that had been on display during the Universal Exhibitions held in London in 1851 and 1855. For this reason, few of his illustrations would have shown his contemporary readership things that were completely unfamiliar to them. But where the book was truly innovative, was in its comprehensive global approach to the field of ornament and beauty.

Left: Plate LXIII, Celtic. Right: Plate LXXVIII, Renaissance

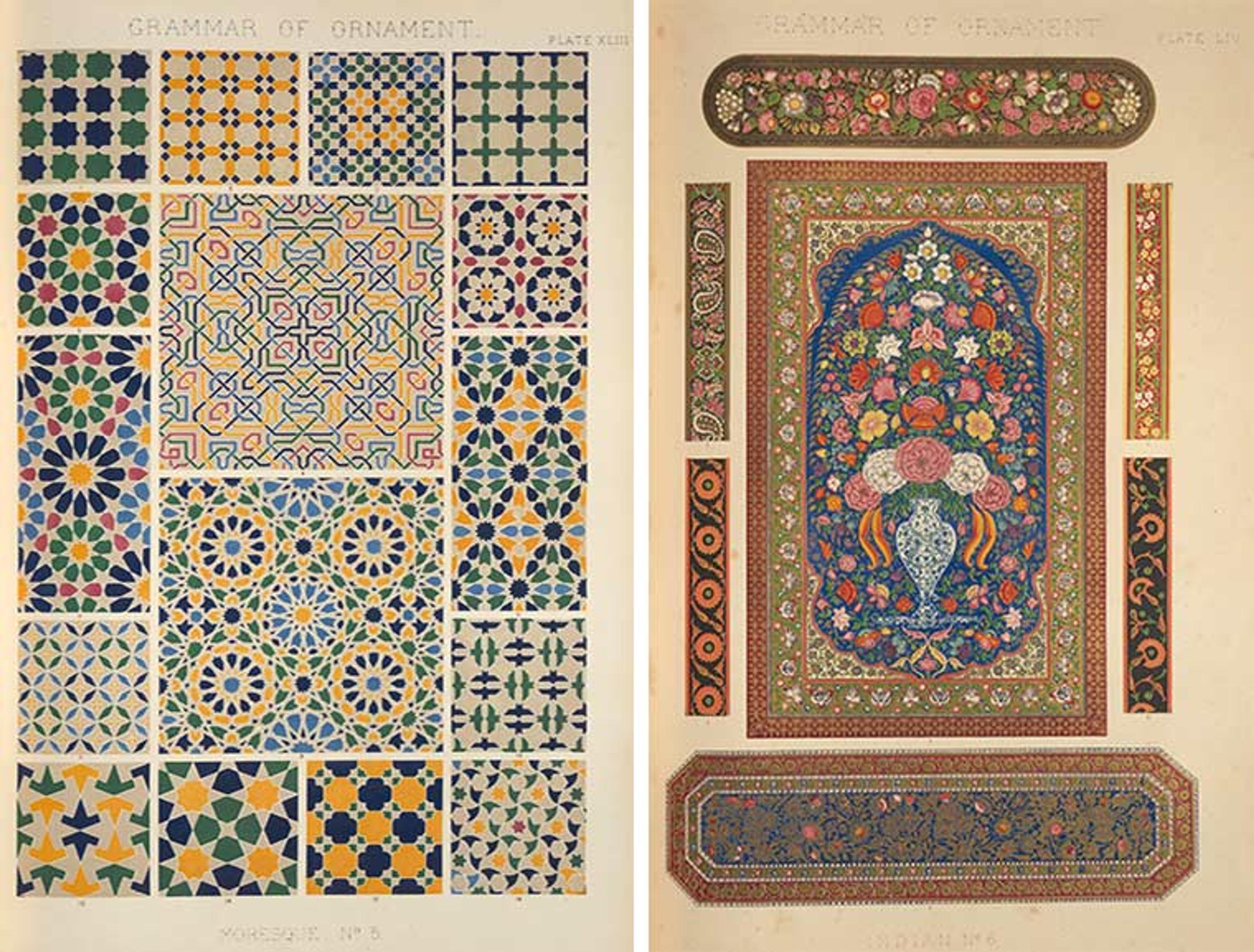

Comparable publications of the period predominantly focused on specific periods or individual buildings. Together with the French architect Jules Goury (1803–1834), Jones himself had published a monographic study of the ornaments and architecture of the Alhambra (1842–45). Such publications were avidly sought after by architects and interior decorators, who used them as sources of inspiration for the decoration of contemporary interiors in an eclectic array of historic styles. The Ibero-Islamic style of the Alhambra, for example, was eagerly adopted for Moorish smoking rooms in England and the United States. Too often, however, the published patterns and designs were copied slavishly instead of inspiring new designs with a similar aesthetic. Jones watched in horror as the practice of copying slowly killed creativity. He therefore took care to emphasize that his Grammar of Ornament was not a pattern book, but a visual manual to mastering the language of beauty. He wrote: "The principles discoverable in the world of the past belong to us; not so the results."

By juxtaposing examples from a great variety of works of art and architecture—from Egyptian capitals and Grecian floor tiles, to Irish picture stones, Italian Majolica, and Indian textiles—Jones hoped artists would look beyond the practical use of the individual examples, and to the implication of the greater whole.

Left: Plate XLIII, Moresque. Right: Plate LIV, Indian

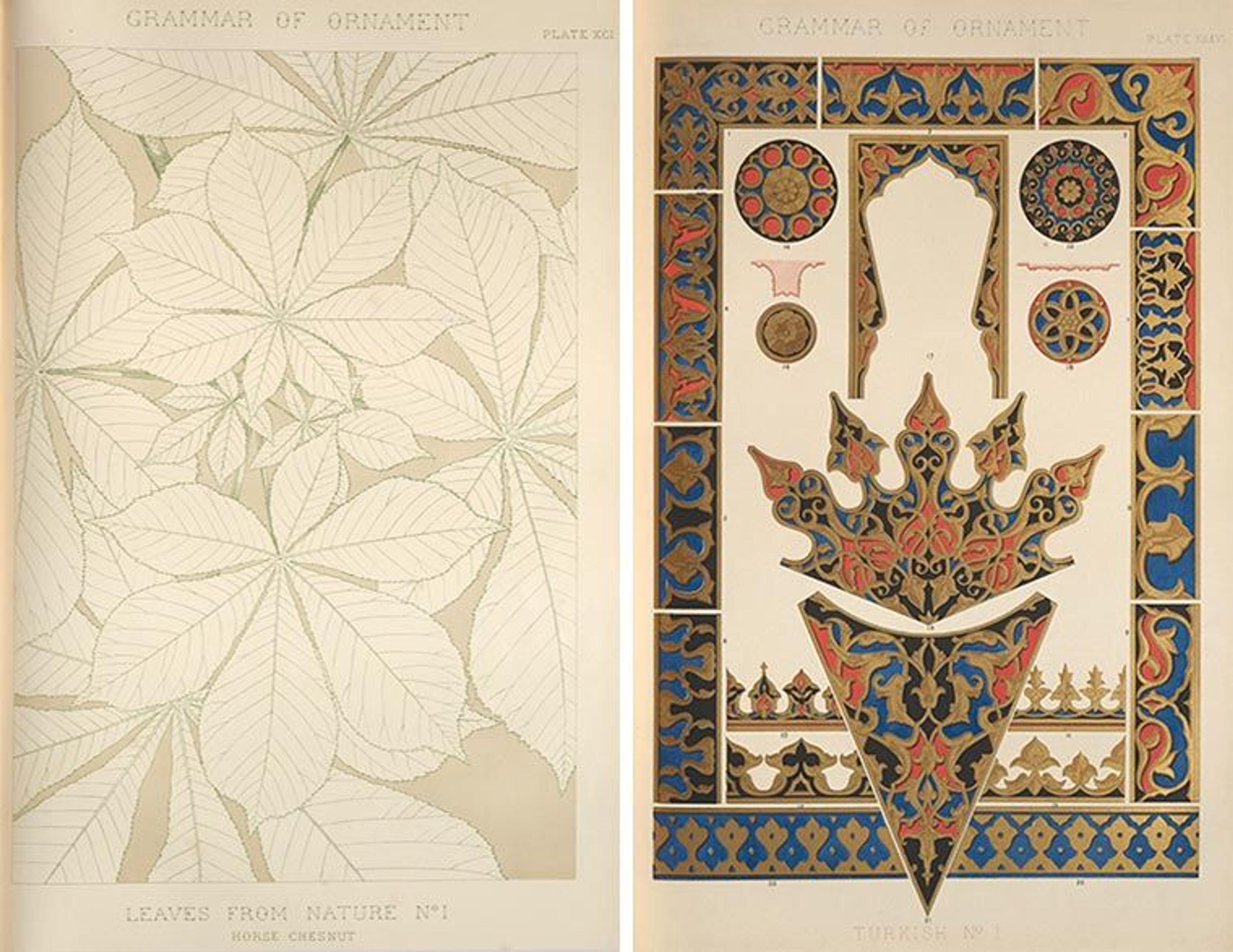

To help his readers crack this underlying code and unleash within the artist's mind an "ever-gushing fountain of creativity," Jones made sure his color plates were preceded by thirty-seven propositions pertaining to proportions, colors, and rules of abstraction, which form the basis of the grammar. Central to his thesis is the notion that anything that is conceived of as beautiful will be in harmony with the laws of nature. This principle remained the same, whether an artist carved the wooden beams of a Hindu temple, tattooed the face of a Maori warrior, or weaved fine Persian textiles. To drive this point home, the final chapter of the book is devoted to "leaves and flowers from nature," presented in various levels of abstraction to emphasize their relationships to the patterns and motifs found on the previous pages.

Left: Plate XCI, Leaves from nature. Right: Plate XXXVI, Turkish

While Jones's ideas slowly took root in art education over the following decades, which in turn influenced the development of new artistic movements such as Arts & Crafts and Art Nouveau, The Grammar of Ornament did not bring about a direct change in artistic practice. In fact, as Jones himself anticipated, we often find patterns and motifs from the book copied and applied to objects and interiors dating from the third quarter of the nineteenth century.

The Grammar was celebrated first and foremost for its outstanding folio-sized color lithographs, which represented the latest and most sophisticated innovations in the field of printmaking. Color lithography had been in use for several decades, but because each color was printed from a separate lithographic stone, most commercial publications were printed in a limited palette of three or four colors. Since color played a crucial role in Jones's work, he took charge of the production himself and employed assistants to work out the patterns on lithographic stones, with certain plates requiring as many as twenty distinct stones. The high quality of Jones's color plates quickly turned the luxurious first edition of the book into a collector's item. Their appeal greatly outlasted Jones’s intellectual arguments, which were omitted altogether in the various posthumous editions, and facsimile reproductions published in the later nineteenth and twentieth century.

Watson Library's editions of Owen Jones's The Grammar of Ornament, with the first 1856 folio edition at front

All of Watson Library's copies of The Grammar of Ornament, including the 1856 folio edition, may be requested online and consulted in our Reading Room. For those who may not be able to travel here in person, a digitized version of the 1856 folio edition is freely available online through a partnership between the Smithsonian Libraries and the Internet Archive.

Femke Speelberg

Associate Curator Femke Speelberg joined the Department of Drawings and Prints in 2011 and is responsible for ornament and architectural drawings, prints, and modelbooks. Her work focuses on the history of design and the transmission of ideas. Femke's research is inherently interdisciplinary, connecting works on paper with artworks, objects, and architecture from the fifteenth to the twentieth century. She often collaborates with other Museum departments on installations and publications. She has curated the exhibitions Living in Style: Five Centuries of Interior Design from the Collection of Drawings and Prints (2013) and Fashion and Virtue: Textile Patterns and the Print Revolution, 1520–1620 (2015).

Robyn Fleming

Robyn Fleming is the Museum librarian for interlibrary services and digital initiatives in Thomas J. Watson Library.