- agata@guidemeflorence.com

- +39 348 135 1329

- Poniedziałek – Sobota 9:00 – 21:00

Art, history and Franciscan spirituality

Florence is so much more than the Uffizi Gallery! Almost at every corner the city surprises you with yet another little treasure: a statue, a tabernacle or some beautiful frescoes.

And then, there are the Florentine churches which preserve countless masterpieces, traces of long and prosperous history of the city. One of these churches is the Franciscan church of Santa Croce founded at the end of the thirteenth century just outside of the city walls in an area vastly populated by the workers involved in the textile production, in cleaning, carding, spinning, weaving and dyeing of the wool. The Franciscans addressed their preaching to this social group scarcely represented by the government.

The order of Franciscans was founded by St. Francis of Assisi, a son of a wealthy merchant who at the certain moment of his life decided to refuse all the earthly goods and chose to live among the poor preaching and spreading the knowledge of the gospels. The number of St. Francis’ followers grew rapidly and not long after the beginning of his activity Francis had to write a rule for his friars to follow. The new order was officially recognized by the pope in 1210. St. Francis died in 1226 and from his death the influence of the order constantly increased. The Franciscans spread across Italy and Europe. At the end the thirteenth century they came to Florence and established themselves outside of the city walls, in an area vastly populated by simple people engaged in the textile production: weavers, dyers and carders. To them the Franciscans directed their preaching.

The church built for the monks was dedicated to the Holy Cross. It was probably designed by Arnolfo di Cambio, the same architect who began the construction of the Florentine cathedral and who planned the Palazzo dei Priori (today’s Palazzo Vecchio). The church was finished around 1335 and consecrated in 1443 by the pope Eugenius IV.

In the Santa Croce area lived not only the poor workers involved in the textile production, but also some very important and wealthy families of merchants and bankers. Among them were Bardi, Peruzzi, Alberti and Cavalcanti. These rich families soon started to support the church and engaged in its decoration.

Already during the fifteenth century, some of the most important Florentines were buried in Santa Croce. Leonardo Bruni, a humanist, historian and Chancellor of Florence was buried here in 1444, Michelangelo in 1564 and Galileo in 1642. With the passing of time Santa Croce became a sort of Italian pantheon and hosts tombs of many important personalities, writers, poets, artists and composers.

The Bardi Chapel

During the thirteenth and the fourteenth centuries the Bardi were one of the most wealthy and influential Florentine families. They were bankers and merchants and until 1345 the Compagnia dei Bardi was the biggest trade company in Florence. The Bardi traded wool, wine, oil and borrowed money on interest. One of their clients was King Edward III of England who received Bardi’s support for the Hundred Years’ War. Because this money was never given back, the Bardi bankrupted in 1345, just like their main competitors, the Peruzzi. The crisis of Bardi and Peruzzi’s banks caused a serious economic decline of Florence and on the ruins of these two trade companies the Medici and the Strozzi would build their fortunes in the years to come.

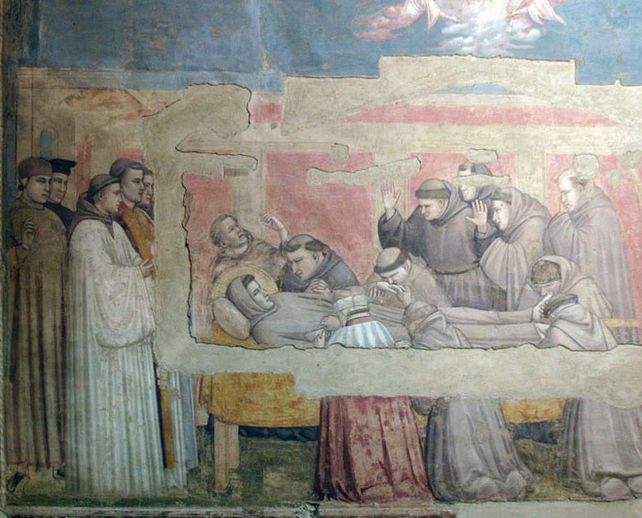

In 1320s Bardi commissioned Giotto, already a very well known and recognized painter, to decorate their chapel in Santa Croce. Giotto painted on the walls the stories of St. Francis, the founder of the Franciscan order. These frescoes allow us to understand the very essence of Giotto’s revolution in painting. If you look at the figures of friars who gathered around the corps of St. Francis, you can admire Giotto’s realism. The faces of the friars are painted with such an attention for detail and expression, that they seem portraits of real people rather that a schematic representation of a human being.

If you look at the scene above, which shows St. Francis appearing to the friars in Arles, you can see Giotto’s innovations in terms of spatial representation. The painter built the space of the chapter room in Arles using intuitive perspective. In the foreground, to reinforce the impression of depth, he painted the monks seen from behind who look at St. Francis and show the spectator their shoulders.

What I love about this chapel, are also the colours. Giotto’s palette is warm and calm. The painter chose the colours of the soil: browns, beiges, greys and built the scenes which are strongly balanced chromatically.

Donatello’s crucifix

Donatello’s wooden crucifix is in the left transept of the church. Giorgio Vasari in his Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors and Architects tells the story of this work sculpted by young Donatello. According to Vasari, after the completion of the crucifix, the sculptor wanted to show this piece to his best friend, Brunelleschi. Probably he expected that Brunelleschi would praise his skills and taste, but instead Donatello received a severe critique. After having seen the crucifix, Brunelleschi said that Donatello crucified a peasant. He invited Donatello to come to his workshop in few weeks’ time and he would show him how to sculpt a proper Christ. One day Donatello wanted to invite Brunelleschi for a common dinner. He went to his workshop with an apron full of eggs. Brunelleschi opened the door and showed Donatello a wooden crucifix that he had just finished. Donatello was so amazed and shocked that he let all the eggs fall on the floor. He admitted that Brunelleschi’s crucifix was done with excellence and perfection.

Brunelleschi’s crucifix mentioned by Vasari is the one from Santa Maria Novella. You can admire it today in the Gondi chapel. Vasari’s story seems just a funny anecdote. However, it tells few important things about the Florentine art. The two crucifixes testify the existence of different currents and tendencies in the Florentine artistic production of the period. Even two good friends, such as Brunelleschi and Donatello, had different points of view on art, different approach in treating human figure, different idea about the sacred art. Donatello’s work from Santa Croce testifies the artist’s interest in realism. Donatello was a careful observer of the world around him. In his art he would always try to copy and imitate nature as closely as possible. Brunelleschi, instead, saw art as a form of abstraction and mathematical perfection. The forms of nature were transformed in his mind, purified and idealized.

The works of the two artists show the two different faces of the fifteenth-century art in Florence.

Michelangelo’s tomb

Michalangelo Buonarroti died in Rome in 1564. He was then almost 89 years old. For a long time before his death, the artist was conscious about his advanced age and prepared himself for the final farewell. Already in 1547, he started to work on a Pietà to be place on his tomb. It is the Bandini Pietà kept today in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo in Florence. Michelangelo did never finish this work. The piece of marble chosen for the statue was so hard that it was impossible for the artist to continue its execution. One day, in a fit of frustration, he even wanted to destroy the Pietà. He caused many damages to it but fortunately the statue was saved by Francesco Bandini who took it from Michelangelo’s workshop and hired Tiberio Calcagni to restore the work and to repair the pieces broken by the master.

After Michelangelo’s death, Giorgio Vasari tried to obtain the statue from Bandini to put it on the artist’s tomb, but he did not succeed in his mission.

Michelangelo’s corps was transferred to Florence and buried in Santa Croce. Vasari projected the tomb that includes Michelangelo’s bust and the allegories of the arts: painting, sculpture, architecture which cry the loss of the master.

Cimabue’s crucifix

In the sacristy of the church you can admire Cimabue’s painted crucifix, the most illustrious victim of the flood of 1966. This crucifix is one of the most ancient works of art preserved in Santa Croce. It was painted around 1265 by Cimabue, Giotto’s master, and marks an important step in the history of medieval painting. The work testifies Cimabue’s interest in shading, more realistic rendering of the human body and representation of emotions and of Christ’s pain.

Until 1966 the crucifix hung in the church in front of the main chapel. During the flood, the impetus of water and dirt dragged the crucifix down. It was rescued by the mud angels, but the damages were enormous. The painting lost 60{6e5c71185e99969cf7ef1fbbc6604490216adbb2e861eba161fa7527b8966e94} of the paint surface. The restoration preserved the remaining parts, but the original aspect of this masterpiece is lost forever.

These are only few among many of the masterpieces gathered in Santa Croce. During your visit, do not forget to admire also the Pazzi Chapel projected by Brunelleschi, the Medici chapel with Bronzino’s Christ in Limbo, Galileo’s tomb and Donatello’s Cavalcanti Annunciation. A visit to Santa Croce is a memorable journey through the centuries of art and history.

Useful information:

Opening hours – From Monday to Saturday from 9:30 am to 5 pm. On Sundays from 2 pm to 5 pm.

Tickets – 8 euro (adults), 6 euro (11 – 17 years old, groups), free (children under 11)

You can find all the information on the Santa Croce website.