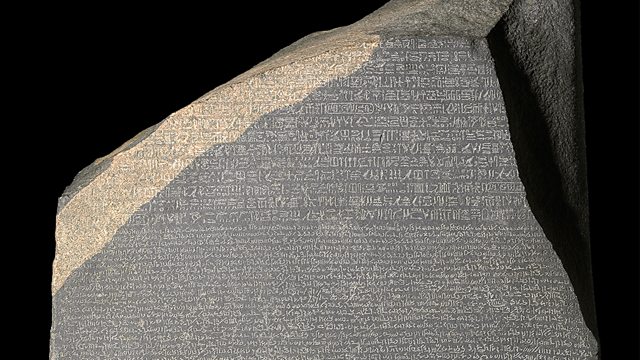

Rosetta Stone

The story behind one of the most familiar objects at the British Museum - the Rosetta Stone. Neil MacGregor describes a power struggle in ancient Egypt

Today's programme finds Neil MacGregor in the company of one of the best known inhabitants of the British Museum - the Rosetta Stone. Throughout this week he is exploring shifting empires and the rise of legendary rulers around the world over 2000 years ago and here he takes us to the Egypt of Ptolemy V. He tells the story of the Greek kings who ruled in Alexandria. He also explains the struggle between the British and the French over the Middle East and their squabble over the stone. And, of course, he describes the astonishing contest that led to the most famous decipherment in history - the cracking of the hieroglyphics on the Rosetta Stone. Historian Dorothy Thompson and the writer Ahdaf Soueif help untangle the tale.

Producer: Anthony Denselow

Last on

![]()

Leaders and Government

More programmes from A History of the World in 100 Objects related to leaders & government

About this object

Location: El-Rashid (Rosetta), Egypt

Culture: Ancient Egypt

Period: 196 BC

Material: Stone

The Rosetta Stone is one of the most famous objects in the British Museum but the actual contents of its inscription is less well-known. The inscription is a decree that affirms the royal cult of the 13-year-old Ptolemy V on the first anniversary of his coronation in 196 BC. The same inscription is written in three different scripts ? Greek, hieroglyphs and demotic Egyptian. It was this Greek inscription that allowed modern scholars to begin to decipher hieroglyphs for the first time.

Why is the Rosetta Stone written in three different scripts?

In 332 BC, Egypt was conquered by Alexander the Great. After Alexander's death, his former general Ptolemy I ruled Egypt. His Greek descendents known as the Ptolemies ruled Egypt for the next 300 years. The Ptolemaic period witnessed a fusion of Greek and Egyptian cultures. Greek was the official language of the court, while hieroglyphs were limited to use by the priests. Demotic Egyptian was the native script used for everyday purposes.

Did you know?

- The Ptolemaic kings frequently practised incest marrying their sisters.

An icon of understanding

By Richard Parkinson, curator, British Museum

Although the Rosetta Stone is a rather heavy stone, it is also a strangely insubstantial and mobile thing.

It was once an inscribed temple stela, one of many, in the shining halls of ancient Sais. It was then a piece of builders’ rubble, then a block in the walls of a medieval fort at Rosetta/el-Rashid, then an exotic antiquity disputed by French and English factions, then war booty in an official treaty, then the key to 4,000 years of an otherwise lost written culture, and gradually an icon of not only this decipherment, but of any decipherment, giving its name to computer programs, language schools, even to satellites.

It has moved from the long demolished temple of Sais through European history into outer space. If it hadn’t been created at a time when Egypt was governed by a Macedonian dynasty, been uncovered by warring nations, been given to Europe and worked on by rival scholars, it would have remained only another duplicate temple inscription.

Instead, its messy war-torn history has somehow made it into an icon of our attempts to understand not only Ancient Egypt, but also other languages and other cultures.

So it is a surprisingly optimistic thing, reminding us that nationalistic conflicts can sometimes end up producing empathy and understanding. Although it has been battered by its long history and is not exactly beautiful, the fact that it still fascinates so many people - including the over six million visitors who see it at the British Museum each year - seems to me utterly wonderful.

Human history is not such a hopeless affair if this heavy piece of granite from Aswan, endlessly fought over, can become a symbol of our desire to understand each other.

Transcript

Broadcasts

- Wed 19 May 2010 09:45BBC Radio 4 FM

- Wed 19 May 2010 19:45BBC Radio 4

- Thu 20 May 2010 00:30BBC Radio 4

- Wed 2 Dec 2020 13:45BBC Radio 4

Featured in...

![]()

Leaders and Government—A History of the World in 100 Objects

More programmes from A History of the World in 100 Objects related to leaders & government

Podcast

-

![]()

A History of the World in 100 Objects

Director of the British Museum, Neil MacGregor, retells humanity's history through objects