Peter Saville Speaks on (Paris), Pop Culture and Pop Art

- TextJo-Ann Furniss

For the Summer/Autumn 2020 issue of Another Man, Peter Saville speaks to Jo-Ann Furniss on Roxy Music, Richard Hamilton, and more

This article is taken from the Summer/Autumn 2020 issue of Another Man:

I am often fond of saying to certain people in the creative industries that without Peter Saville we would not exist. I absolutely believe this to be true – at least we would not exist in the form that we do today without his example, the work he has produced, and his classroom of high art pop culture that taught so many of us at such a formative age. In fact, we might never have entered into our professions at all without him. It is particularly Peter’s work in the music industry that became a portal to another world, in the didactic form of record covers that thrust “Art into Life”. These secretive, seductive products, which could be seen as Postmodern in their appropriation and yet had a thoroughly Modernist agenda – “Art into Life” is a quote from Vladimir Tatlin after all – taught many of us as teenagers. And this was just as Peter himself had been taught by Roxy Music and just as Bryan Ferry had been taught by Richard Hamilton at art college. This cascading influence of Pop and pop culture continues today: Richard Hamilton is still a startling herald of the now – and kind of the godfather of us all – despite his death in 2011; the first Roxy Music album of 1972 says as much about the 21st century as the 20th; and Peter Saville’s products, alongside the often sublime music contained within, have been dispersed in a different, less physical way. The Saville style has become part of the fabric of the everyday, for both good and ill. As Peter says, “Be careful what you wish for.”

(PARIS) in brackets

Peter Saville: On reflection, I have had quite a fractious relationship with Paris. I think I can define it in two eras. In the 80s I always liked it, but something unsettling, disappointing or traumatic would always happen. I would come home and ask myself, ‘What is it about Paris?’ Something would always happen, something quintessentially Parisian – something to do with the people, culture or language, just something. There was always a sense of love-hate, in that clichéd Paris sense that it is like a beautiful woman: it’s a bumpy ride.

Since the millennium, it has really been quite different. The challenging and upsetting moments have somehow kind of faded away; it doesn’t happen now. I enjoy myself in Paris and I don’t get slapped in the face by it any more. And now, I always have the same question when I am in Paris: ‘Why don’t I live here?’

Then I remember why I don’t live there. One is a practical thing, based on the diverse nature of my work and how the networks of involvement are still very UK and London-centric. It is actually practical and useful for me to be in London. Then there is the philosophical view, and that’s potentially the danger of being too much in your comfort zone. In London, there is a certain friction between Britishness and me. In Paris, in the way of things and the culture of Paris, it is almost too comfortable; it indulges, or it would indulge, too much of one side of my personality. It would be very easy to become a Parisian me, and that might not be a character I would be so happy about. It would be enjoyable, but it might not be really me.

Like a cartoon, endlessly smoking Gauloises?

Well, yes. I would not like to indulge too much of that side of my personality. It reminds me of a card I did for Yohji 30 years ago. It said, ‘Being without some of the things you want is an essential part of happiness.’ So Paris might overly indulge one aspect of my personality, and to some extent starve another. That’s the balance of my opinion on a Eurostar return journey at least.

Everyone has different sensibilities about where they come from. I appreciate enormously the values I absorbed in the first 25 years of my life in the north of England but my ambition was for something else. I could have slipped into a sense of decadence in Paris and done little. I could have become lost there. Paris addresses some of my less desirable sensibilities. Manchester established my values.

Putting it bluntly, in Manchester somebody might well pull you up on something and call you a cunt. That will not necessarily happen in London. And in Paris people might just say, ‘You are amazing and I like your shoes...’

‘...You cunt!’

People admire image in Paris. It is a very feminine city. There are ways of being, walking, dressing, putting a scarf on that are just... chic. And it’s normal. It can look very mannered in other places. I am just a bit arm’s length from it and quite amused by it.

That’s because you grew up in Manchester and actually think it’s all a bit poncey.

Well, yes.

But you like it nonetheless.

It is automatic for me. Which is why I have always been a little bit sceptical of it. Things that are so automatic to one are not necessarily good for you. I am far more camp in Paris than I am even in London. I probably feel a little bit more special because I don’t live there, rather than living there and the event being taken for granted. Anyway it doesn’t really matter; I have managed to get to 64 without worrying about it.

That said, as I am approaching my ‘late period’, it would not bother me at all to spend a few months each year in Paris. In fact, I’d quite like to. There are things about me that fit.

You look French.

Well, whatever.

There are some great advocates of my work in Paris. And the style of my work is recognisable and recognised there.

There has always been a European sheen to it.

To be in the north of England, dreaming of an avant- garde kind of life when you are really young, thinking about the 20s, because the 20s in Paris seems inextricably linked to all of that... Dreaming of high art and pop culture.

For me, it was the late 60s and early 70s, the jet-set. I remember being driven out to just look at the airport – Ringway Airport, Manchester. The very idea of an airport was exotic. And one day, I was driven out to the airport in an E-Type Jag – I was probably about nine years old. That would have been 1964 and that was one of the most exciting days of my life.

The airport was kind of a window to ways of life I was fascinated by, like James Bond movies. I remember going on family trips to London and I remember distinctly asking my father why nobody lived in Manchester, I mean why nobody lived in the city. I was very taken by the fact that people lived in the centre of the city. Basically, what I was noticing was the cosmopolitan way of life. It became set as an ideal for me and remains so. To that end Paris, and one or two other European cities, align with my aspiration far more than London has done. London is not really yet cosmopolitan in that everyday living sense. So it is still on my agenda to make it to one of those places.

There is also part of me that wants to be in a Slim Aarons photo by a pool. There was the cover of Another Time, Another Place, the gatefold with Bryan Ferry in that white tuxedo on the front. But what was important to me was how it opened up, with that image of a cocktail gathering of jet-set-looking persons around a pool. I remember as a teenager wanting to get there.

ROXY MUSIC was my art school

Well, pop culture has always performed this remarkable service of introducing and opening up young formative minds to art, politics, gender, ways of being that more than likely, the circumstances of one’s own existence have not brought about. You are introduced to possibilities, the richness and complexity of life through this very compelling medium of music and the people who make that music. It is already there through books, television, newspapers, the internet, so much is there, but seemingly it makes this enormous difference when these role models become the ambassadors and avatars of these ideas. Say it is on a Rolling Stones cover; it is validated because you like the Rolling Stones. The UK has always been this crucible of youth culture and, in my opinion, in this entire post-war period pop culture has been one of the greatest educators of an evolving society. It is through the frame of pop that so many of us have been introduced to new ideas and new possibilities at this fundamentally formative time in our lives, say between 12 and 20. It is a really important time to be introduced to ideas outside the family, outside the education system. Tony Wilson would often refer to ‘the art of the playground’ and that really upset me in my early 20s – I didn’t want to think I was making the art of the playground. But when I look back on that now, there is almost nothing more formative than the art of the playground – the first cut is the deepest.

I have my own version of it. I have Roxy, The Velvet Underground, Leonard Cohen, David Bowie, Bob Dylan, The Beatles, the artists who shaped my taste and my way of seeing things. And I know how my work has performed exactly the same function to other people. Those record covers have acted as portals of interest and awareness for other people. This is really important and it both irritates and saddens me that some of these pillars of youth culture are not as formally recognised and appreciated as they should be. Pop is marginalised. People grow up and they wish to define themselves with more elite, obscure and esoteric associations.

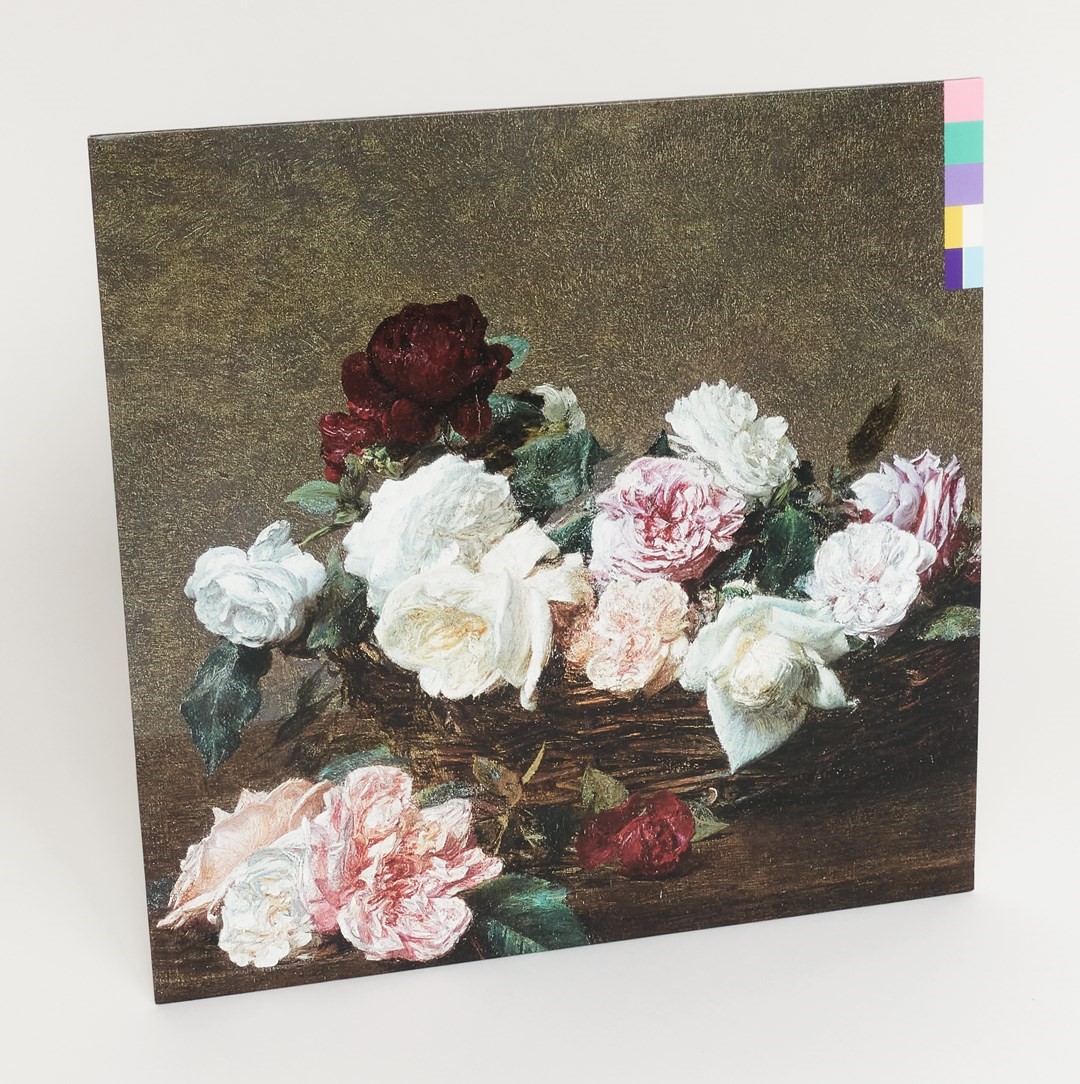

“WITH FACTORY, I DIDN’T DO WHAT I WANTED; I DID WHAT I WANTED TO HAVE. FACTORY ALLOWED ME THE AUTONOMY TO CRAFT THINGS AS POSSESSIONS – FOR YOUNG PEOPLE RECORD COVERS WERE ALMOST THEIR FIRST CULTURAL POSSESSIONS. WHAT I WAS INTRODUCED TO VIA POP AND BUILT UPON AT ART COLLEGE WAS HOW THOSE THINGS COULD LOOK AND WHAT THEY COULD BE. I REQUISITIONED THE TROPES OF HIGH CULTURE AND REDISTRIBUTED THEM TO THE PEOPLE. TO SOME EXTENT, I RAIDED THE ARCHIVES OF THE MUSEUMS AND GAVE IT ALL AWAY.”

The fundaments of pop culture get parked in the sphere of juvenilia, which is not entirely appropriate.

So it’s almost Freudian.

Exactly. And it is not yet fully appreciated. For example, Bob Dylan gets a Nobel Prize in his 70s. I mean, Bob Dylan should have got a Nobel Prize in his 30s; but that’s how long it takes. If you’re a figure in pop culture, how long do you have to wait for establishment acknowledgement that what you did was fundamentally important?

In the 80s, it felt like there was a massive ambition for pop culture, particularly with you and Factory, Paul Morley and ZTT. There was an idea of high art pop culture – a dream world adjacent to the real world. The portals were right there, your posters on buildings and things you could hold in your hands, like record covers, these strange monoliths.

They were also possessions. With Factory, I didn’t do what I wanted; I did what I wanted to have. Factory allowed me the autonomy to craft things as possessions – for young people record covers were almost their first cultural possessions. What I was introduced to via pop and built upon at art college was how those things could look and what they could be. I requisitioned the tropes of high culture and redistributed them to the people. To some extent, I raided the archives of the museums and gave it all away.

These were things I wanted. As an aspirational adolescent from a middle-class family in the north of England, growing up in Hale of all places, I wanted the ephemera of high culture once I began to see it. So I simulated it and, interestingly enough, other people wanted it too once they had seen it. I was just the conduit from which it passed from the canon to the everyday; that was the function performed. Why it was me has a lot to do with family and just the social coordinate, above all I was given the freedom to do it. I am sure there are many others who would have done it too if their freedom to access the audience had been the same as mine. The freedom I had at Factory was and remains unprecedented in the field of communication design, absolutely and utterly unprecedented. Nobody commissions communications work and transfers authorship to the graphic designer. The graphic designer is not the author of the content, the content comes from they that wish to communicate; you are somebody else’s messenger. You might nuance the message to some extent, but it is somebody else’s message. The unprecedented thing that happened to me at Factory was that through Joy Division and New Order and a set of exceptional circumstances, I was allowed authorship. Rob Gretton would remind me, we allow you this – thank you, Rob. I was able to literally share the things informing and exciting me, via a zeitgeist filter/balance that I was running in my own self, to a wide audience. And it became a very wide audience by the time you get to Blue Monday; I am told two million people.

It has never happened to me since then. It happened for just over a decade. I was able to select to the pulse beat of an interdisciplinary zeitgeist, things from the canon of culture and share them with this ever-expanding audience. And because of the context in which they saw those things, because they liked Joy Division and New Order, they wanted to like the imagery that came with it. It was endorsed by these avatars and ambassadors that they had signed up to because the work was wrapped around a record. Some people liked it and some didn’t. Someone said to me recently that this was a catalyst of visual literacy in this country, which is rather grand, but it does say something about pop culture as an educator. In pop culture I include film, television and fashion. Pop culture has been the great educator to the evolving mass society.

Saying that, over the past ten to 20 years, I have been concerned by the devaluation of the canonical code as a result of the abusive practices it has been exposed to. I contributed to a practice that I naively did not foresee the abuse of. It saddens me now to see the once sacrosanct higher codes used and devalued to sell air miles or train tickets or spurious insurances, banking or healthcare. I am despondent about that and I look at it sometimes and think, I am to blame. Unwittingly, I am culpable to contributing to that and ultimately the utter meaningless of everything. My disinterest is not just to do with age, it is ennui. Everything, everywhere, all the time. It’s really tiresome.

A good album title though.

Could be.

Somebody asked me about luxury recently. They asked me what my interpretation of luxury was and my answer was withdrawal. The greatest luxury I can imagine is not having to care, withdrawing from the field. There is a line in Dylan’s Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues, ‘I’m going back to New York City, I do believe I’ve had enough.’ It’s like that...

Anyway, to go back to the beginning, I did say that Roxy Music was my art school. This came up, rather poignantly, with Michael Bracewell when he was writing his Roxy book about the early formation of the band. I proposed that Roxy was perhaps the first postmodern group. That’s why it connected with me and my own emergent sensibilities so strongly. It was perhaps in the early 70s that the 20th century’s fin-de-siècle moment prematurely occurred. There was an uncertainty about tomorrow that resulted in a reflection on the past, the notion of progress had temporarily run its course and there was a certain anti-climax to the decade. The socio-cultural optimism that had empowered the 60s was at an end; so many things had not worked that it brought about a certain kind of malaise. The future became discredited and hence the postmodern break. As a teenager, Roxy was my postmodern intro; a collage of stylistic, historic fragments introducing me to new names, places, thoughts and even textures. Roxy in general, Bryan specifically, in intellectual and sartorial terms, introduced me to many things I did not know about – it was like having a professor nurturing my awareness.

Of course, Bryan Ferry’s teacher at art school was Richard Hamilton.

RICHARD HAMILTON and the importance of a toaster

The art period I actually knew a little about in my late teens was Pop Art. It happened in real time to my life – I was five in 1960 and 15 in 1970 – so I saw this thing called Pop Art happening. I was aware of American Pop first and then subsequently came to understand its formative and philosophical origins in Britain with the Independent Group of which Richard Hamilton was a significant member. Pop Art was something I could find a way into and understand a little of. I did not understand it as part of an art discourse when I was a teenager, therefore I had my own adolescent misreading of Pop. I thought it was an acknowledgement of the aesthetics of a commercial environment, particularly an American commercial environment as art, that it was the recognition of a Brillo box as art. Of course, that was quite simplistic, but it suited my limited awareness that the things I liked and knew about were being recognised in the context of fine art.

In my last years at grammar school, Malcolm Garrett and I were equally obsessed with the British Pop artist Peter Phillips. He referenced pin-ups, cars and elements of technology and industry within assemblages with names like Custom Painting No.5. All things that we could understand and like, actually very adolescent imagery, but put together fabulously in paintings. It was like the world one already inhabited was now recognised as art, although that was not quite the full story. But then there was Richard Hamilton.

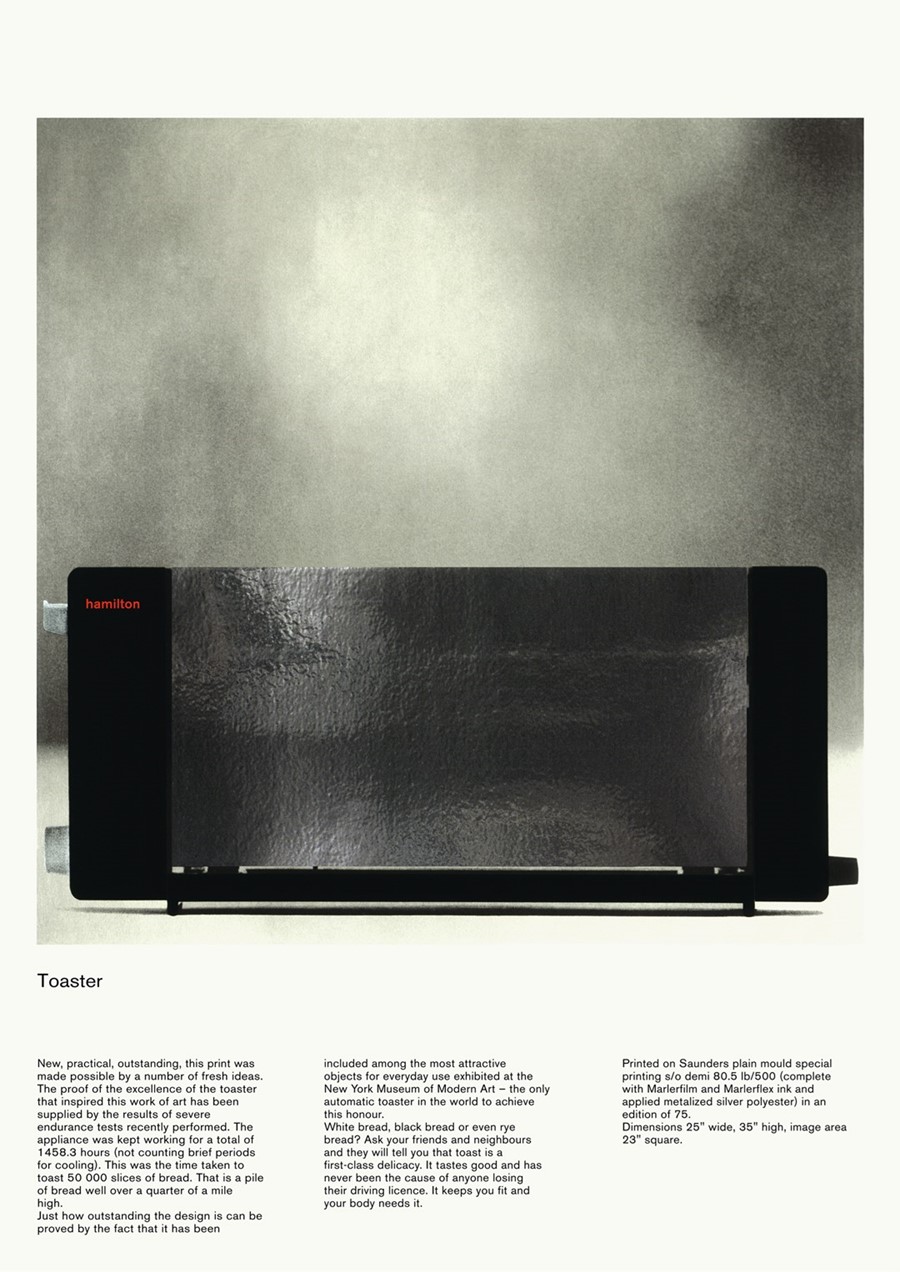

I don’t know if I knew that much about Richard Hamilton, but one day in the early 70s I picked up a book in the library of the graphics department of Manchester Polytechnic. I saw ‘Richard Hamilton’ on the spine and that was a name I knew. So I picked it up and flipped through it. I saw things in it that I recognised and I was probably pretty taken by the cover itself, and then I saw the work Toaster. What I believed I was seeing was a conflation of the things I was interested in and studying. I recognised this rendering of a toaster in a celebratory rather than an ironic way.

There was a longing...

Yes. It was not a parody of a consumer product; this was something seemingly in praise of a consumer product. It was an image that was somewhere between 2D and 3D through the use of mirror foil, but basically it was a Braun toaster. I knew enough to be able to appreciate the values of Modernism epitomised by Dieter Rams’ work at Braun. Hamilton was not making fun, this was not some American toaster; this was not a Rosenquist with toast popping up; this was something a little more serious. Also it was an art edition with typography! And I looked at that and I thought, that’s a graphic work, unadulterated. It is not a graphic work reinvented by an artist, it is not a silk-screen like a Warhol; it is a graphic work. This is what I was studying and this had graphic design, product design, still life photography and typography all inherent within one work. I was not aware that I took all of that in at the time.

I did not see it again for 20 years.

One day, ‘round about ‘95, I walked into Tommy Roberts’ Pop gallery shop called TomTom, and that’s when I saw the print again – this time in real life at full size with the foil and the type. And I had to sit down on the nearest 60s armchair. You know how they say that when you are drowning your life flashes by in seconds, well, my entire portfolio flashed by. I saw this print and I went, ‘Oh, that’s Factory Records.’ The use of materials, the strictness within a corporate system, the appropriation of formal codes for cultural communication, the entire look and feel of it: it was what I had been doing, it was what I had done. It really disturbed me because I was unaware. I had not kept that book, I had not made it a conscious model to follow. Yet the whole thing, the conceptual approach, had downloaded in seconds and shaped my way of doing things.

The print was £2,000 and it was £2,000 more than I could afford in 1995. I regret that I was not able to just buy it, as a kind of tribute. And I still don’t have one. Basically, Richard Hamilton showed me what to do, as a template to follow. Most importantly, I perceived in that work a coordinate where art and design and all attendant disciplines converged. I went to a ‘Faculty of Art and Design’ and I did not see a distinction between the two. It was not so much a failure to recognise it but a refusal to recognise that there was a demarcation between the two. That design could be understood as art in the everyday. And I’ve just returned from Florence where art is everywhere in the fabric of the city. The artists, the sculptors, the architects worked collectively on the fabric of being. And it is this idealistic notion of being that was set for me by Toaster in 1975.

Of course, Richard Hamilton’s work Epiphany says SLIP IT TO ME.

A version of this feature will appear in the forthcoming book: M to M of M/M (Paris) Vol.2, published by Thames & Hudson, London in October 2020.

The Summer/Autumn 2020 ‘High Art Pop Culture’ issue of Another Man is now on sale internationally. Head here to buy a copy.