The Logierait Poorhouse (officially known as the Atholl, Weem and Breadalbane Poorhouse) opened in 1864 in the small rural village of Logierait in Highland Perthshire, Scotland. The purpose of the poorhouse was to provide shelter, food, clothing and medical attention for the old, sick, infirm, destitute, physically and mentally disabled, who were known as inmates. Orphaned or deserted children were also looked after but usual practice was to board out or foster children with local families. Temporary relief was provided to single women and widows with children and to pregnant women whilst they gave birth.

Atholl, Weem and Breadalbane Poorhouse / Cuil an Daraich Home c1940s-1960s. [1]

Following an Act of Parliament in 1845 (The Scottish Poor Law Amendment Act), each parish in Scotland established a parochial board (a pre-curser to today’s local councils) which was encouraged to build a poorhouse to house the destitute and disabled in their area. Small parishes could form unions and come together to share the costs. In Highland Perthshire, eleven parishes came together to form a union with each contributing towards the cost of the poorhouse. This was cheaper and more efficient than having a poorhouse in each parish as the rural population was spread across a wide geographical area in small hamlets and crofts around the lochs and glens of the area, with a few small towns such as Aberfeldy and Pitlochry.

The Poorhouse Union covered the Highland Perthshire parishes of Blair Atholl, Dowally and Dunkeld, Dull, Fortingall, Kenmore, Killin, Little Dunkeld, Logierait, Moulin, Weem and Caputh in the lowland region. The combined area of these parishes was 1248 square miles (848,267 acres) with a total population of 20,852 in 1861, which had declined to 18,810 by 1891 (Scotland Census, 1861, 1891).

The poor were categorised as deserving and undeserving. The deserving poor were eligible for poor relief and included the elderly, infirm, sick, orphaned or widowed, deserted wives – those whose destitution was considered no fault of their own.

Women were more likely to experience poverty than men as they earned substantially less and this was exacerbated if they had to raise children as single parents. Married women whose husbands were away or were widowed would receive ‘outdoor relief’ meaning that they were provided with money, clothes, food, fuel or medical aid in their own homes.

A woman and her two barefoot children in a slum in Old Vennell, off High Street, Glasgow 1868 (Thomas Annan). [2]

Those with no family or friends to care for them were offered bed and board in the poorhouse to save them from destitution and starvation.

The undeserving poor were thought to have brought their own destitution upon themselves. These included unmarried pregnant women or those with illegitimate children who were considered to be a drain on parish funds. The only poor relief these women could claim was by entry to the poorhouse. This was supposed to act as a deterrent to having more children. No fault was applied to errant fathers, although these were tracked down where possible to contribute to child support.

The offer of Poorhouse relief was used as a ‘test’ to distinguish between those unwilling or unable to support themselves. Poorhouse relief was very basic and associated with stigma, so only the most desperate in need would accept this kind of relief. This in turn would keep costs down for the parish parochial boards. In addition, the requirement for paupers to be both disabled and destitute, meant that parochial boards would often reject claims of ‘disabled’ paupers who were elderly or infirm, but were not considered destitute whilst they had living relatives to support them.

Scottish poorhouses were different to the notorious workhouses of England and Wales where the able-bodied unemployed could claim poor relief.

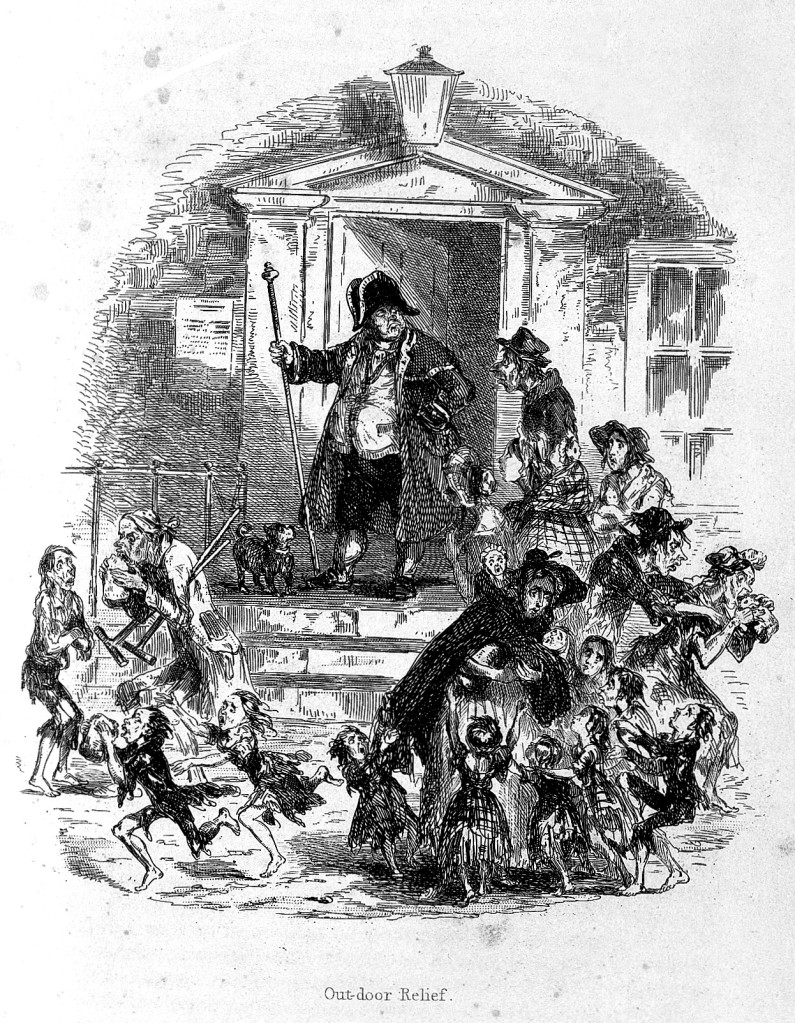

The workhouse was harsh with punishing work and miserable living conditions. It was intended to be harder than the worst jobs available to encourage the poor to get a job instead of claiming aid. It was thought that if a person was physically able to work and did not have a job, it was due to their laziness rather than unemployment caused by economic conditions.

Poor people coming to a workhouse for food (c1840). [3]

In Scotland, there had never been poor relief for the unemployed, so there was no need to build workhouses to punish them. Scottish poorhouses were more comparable to old people’s homes, care for the ill and disabled and homeless shelters. Inmates were still expected to work if they could to earn their keep, with women undertaking domestic chores and sewing. The men helped by providing manual labour and worked in the garden to cultivate vegetables for food.

The image below shows the Logierait Poorhouse from the back in summer c1940-1960. The single story building to the left was the mortuary which was known as the dead house and the other building to the right was the laundry. Clearly visible are the vegetable gardens and washing lines.

Logierait Poorhouse / Cuil an Daraich Home from the back c1940s-1960s. [4]

There was also a difference between the large urban city poorhouses which provided refuge for people from all over the UK and immigrants from Ireland passing through for work and the small rural poorhouses which catered to local residents who were mostly farm workers or from the trades that supported them.

Logierait Poorhouse was built to accommodate 110 inmates, but generally only housed between 40 and 50 people. The poor were not a homogenous group that could be easily categorised. Each person had a different story with life challenges that had brought them to seek help for their destitute circumstances. Most working class people experienced temporary periods of extreme hardship when work dried up or illness or old age prevented them from working. Pregnant women whose husbands were working away, had died or were in prison fell on hard times without a male wage and needed a safe haven to give birth. Orphaned children needed temporary help until they were boarded by local residents or employers. The poorhouse regularly had people coming and going as their aid came to an end. The only long-term inmates were the elderly, disabled and infirm who had no family to care for them.

The first entrants to the poorhouse following its opening on 27 January 1864 were Mary Holmes (or McKay) aged 79 and Jean Stewart aged 82. Both women were widows living in Logierait.

Mary’s occupation was a hawker, a street vendor who went from place to place selling her wares. She was admitted due to infirmity from old age. She apparently was well behaved as her conduct was regarded as good. Mary was in and out of the poorhouse a number a times before she left at her own request on 17 April 1865.

Jean Stewart was listed as a vagrant, meaning she was homeless and wandered the streets in search of handouts of food or money. Vagrants were regarded as a problem and begging was frowned upon. Jean seems to have been rather troublesome as her behaviour is recorded as disorderly and she kept complaining about the food and annoying the other inmates! She was punished by being removed from the main ward and put in the probationary ward for 48 hours. This was where others regarded as undesirable were initially housed. All cheese and potatoes were also withheld from her diet during this period. Jean remained in the poorhouse until her death on 30 April 1868 from general weakness and rheumatism.

The Logierait Poorhouse continued to operate as the Atholl, Weem and Breadalbane Poorhouse into the 1920s when it became known as the Cuil An Daraich home. Parish councils became redundant in 1929 and larger councils or local authorities were established and took on the role of distributing poor relief. It was not until 1948 that the poor laws were finally abolished and replaced by the National Insurance Act of 1948 which created social security. In the same year the National Health Service was created which took on the responsibility of providing free health care. Cuil An Daraich continued to operate as an old people’s home until 1985 and is now the lovely Cuil An Daraich Guest House.

For more in-depth information about the Logierait Poorhouse, read my dissertation, Poverty and the Poorhouse: The Impact of The Gender, Family and Migration on the Provision of Welfare in Highland Perthshire 1864 – 1884.

I am also currently writing a local history book about the Logierait Poorhouse and will provide more information once this is available.

The lives of the female poorhouse inmates will be explored further on the Herstories blog page.

Image Credits

[1] Atholl, Weem and Breadalbane Poorhouse / Cuil an Daraich Home c1940-1960. Image courtesy of Cuil an Daraich Guesthouse.

[2] Old Vennell, off High Street, Glasgow 1868 (Thomas Annan), Public Domain image from the British Library.

[3] Caricature of poor people coming to a workhouse to get food by Phiz (?)(c1840) from the Wellcome Trust Collection. Creative Commons licence through Wikimedia Commons.

[4] Atholl, Weem and Breadalbane Poorhouse / Cuil an Daraich Home c1940-1960 from the back showing the gardens and washing green. Image courtesy of Cuil an Daraich Guesthouse.

Copyright (c) Ruth Washbrook 2023 / third party copyright holders