Insects are the incredible engine room of the planet ensuring ecosystems work. They are under siege by human-caused #climatechange #deforestation #pollution. Report via @PNASnews. Help them and #Boycott4Wildlife

Tweet

Although conservation efforts have historically focused attention on protecting rare, charismatic, and endangered species, the “insect apocalypse” presents a different challenge. In addition to the loss of rare taxa, many reports mention sweeping declines of formerly abundant insects [e.g., Warren et al. (29)], raising concerns about ecosystem function.

This report was originally published in PNAS

Insect decline in the Anthropocene: Death by a thousand cuts David L. Wagner, Eliza M. Grames, Matthew L. Forister, May R. Berenbaum, and David Stopak. January 11, 2021

118 (2) e2023989118 https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2023989118

Nature is under siege

In the last 10,000 years the human population has grown from 1 million to 7.8 billion. Much of Earth’s arable lands are already in agriculture (1), millions of acres of tropical forest are cleared each year (2, 3), atmospheric CO2 levels are at their highest concentrations in more than 3 million y (4), and climates are erratically and steadily changing from pole to pole, triggering unprecedented droughts, fires, and floods across continents.

Indeed, most biologists agree that the world has entered its sixth mass extinction event, the first since the end of the Cretaceous Period 66 million y ago, when more than 80% of all species, including the nonavian dinosaurs, perished.

Ongoing losses have been clearly demonstrated for better-studied groups of organisms. Terrestrial vertebrate population sizes and ranges have contracted by one-third, and many mammals have experienced range declines of at least 80% over the last century (5).

A 2019 assessment suggests that half of all amphibians are imperiled (2.5% of which have recently gone extinct) (6). Bird numbers across North America have fallen by 2.9 billion since 1970 (7). Prospects for the world’s coral reefs, beyond the middle of this century, could scarcely be more dire (8). A 2020 United Nations report estimated that more than a million species are in danger of extinction over the next few decades (9), but also see the more bridled assessments in refs. 10 and 11.

Loss of Abundant Species

Insects comprise much of the animal biomass linking primary producers and consumers, as well as higher-level consumers in freshwater and terrestrial food webs. Situated at the nexus of many trophic links, many numerically abundant insects provide ecosystem services upon which humans depend: the pollination of fruits, vegetables, and nuts; the biological control of weeds, agricultural pests, disease vectors, and other organisms that compete with humans or threaten their quality of life; and the macrodecomposition of leaves and wood and removal of dung and carrion, which contribute to nutrient cycling, soil formation, and water purification. Clearly, severe insect declines can potentially have global ecological and economic consequences.

Insect diversity

- (A) Pennants (Libellulidae): Dragonflies are among the most familiar and popular insects, renowned for their appetite for mosquitoes.

- (B) Robber flies (Asilidae): These sit-and-wait predators often perch on twigs that allow them to ambush passing prey; accordingly they have enormous eyes.

- (C) Katydids (Tettigoniidae): This individual is one molt away from having wings long enough to fly (that also will be used to produce its mating song).

- (D) Bumble bees (Apidae): Important pollinators in temperate, montane, and subpolar regions especially of heaths (including blueberries and cranberries).

- (E) Wasp moths (Erebidae): Compelling mimics that are hyperdiverse in tropical forests; many are toxic and unpalatable to vertebrates.

- (F) Leafhoppers (Cicadellidae): A diverse family with 20,000 species, some of which are important plant pests; many communicate with each other by vibrating their messages through a shared substrate.

- (G) Cuckoo wasps (Chrysididae): Striking armored wasps that enter nests of other bees—virtually impermeable to stings—to lay their eggs in brood cells of a host bee.

- (H) Tortoise beetles (Chrysomelidae): Mostly tropical plant feeders; this larva is advertising its unpalatability with bold yellow, black, and cream colors.

- (I) Mantises (Mantidae): These voracious sit-and-wait predators have acute eyesight and rapid predatory strikes; prey are instantly impaled and held in place by the sharp foreleg spines.

- (J) Emerald moths (Geometridae): Diverse family of primarily forest insects; their caterpillars include the familiar inchworms.

- (K) Tiger beetles (Cicindelidae): “Tigers” use acute vision and long legs to run down their prey, which are dispatched with their huge jaws.

- (L) Planthoppers (Fulgoridae): Tropical family of splendid insects, whose snouts are curiously varied and, in a few lineages, account for half the body mass. Images credit: Michael Thomas (photographer).

The Stressors

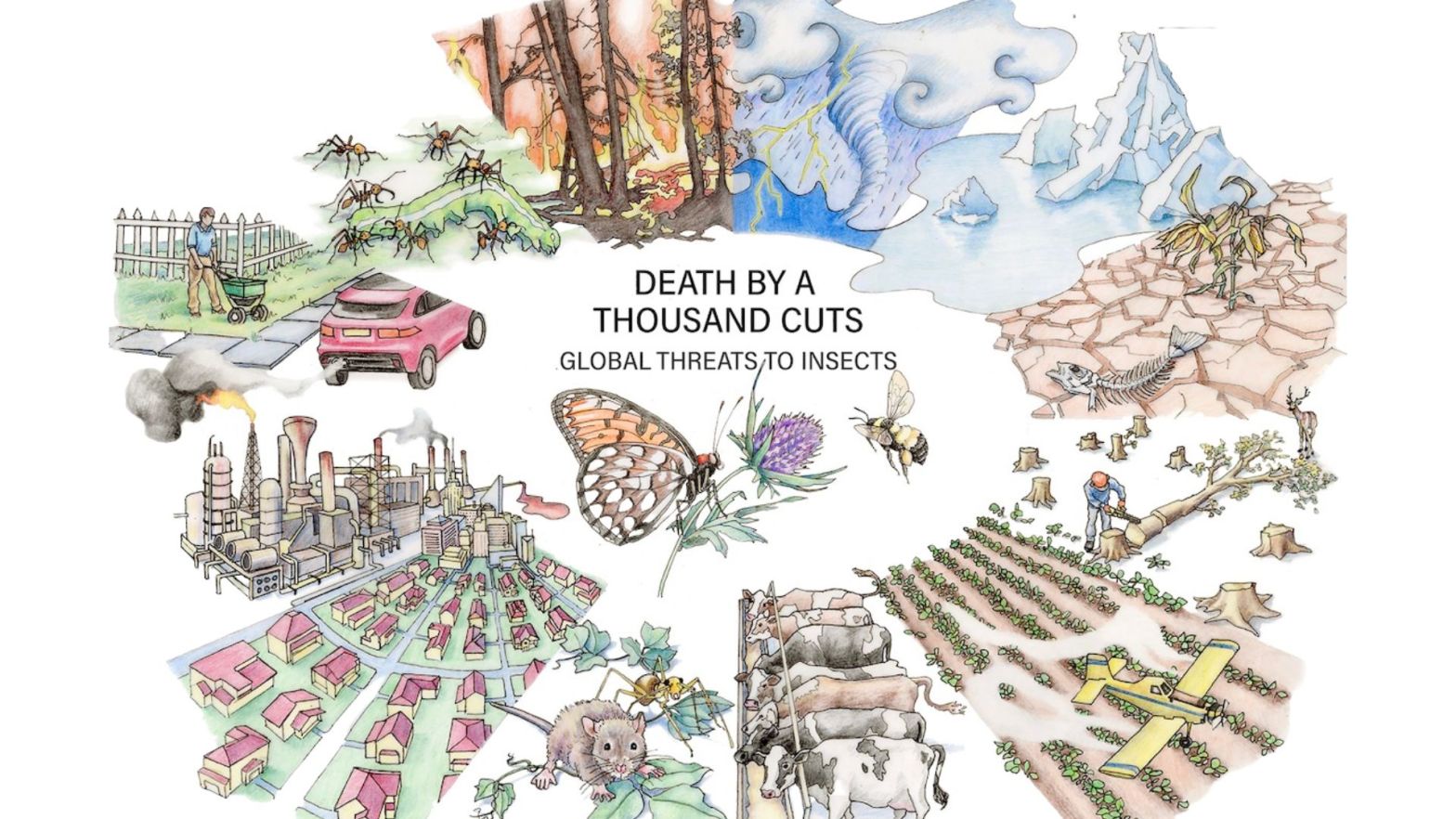

Abundant evidence demonstrates that the principal stressors—land-use change (especially deforestation), climate change, agriculture, introduced species, nitrification, and pollution—underlying insect declines are those also affecting other organisms.

Locally and regionally, insects are challenged by additional stressors, such as insecticides, herbicides, urbanization, and light pollution. In areas of high human activity, where insect declines are most conspicuous, multiple stressors occur simultaneously.

Considerable uncertainty remains about the relative importance of these stressors, their interactions, and the temporal and spatial variations in their intensity. Hallmann et al. (13), in their review of the dramatic losses of flying insects from the Krefeld region, noted that no simple cause had emerged and that “weather, land use, and [changed] habitat characteristics cannot explain this overall decline…”

When asked about his group’s early findings of downward population trends in insects (12), Dirzo summed up his thinking by stating that the falling numbers were likely due to a

“multiplicity of factors, most likely with habitat destruction, deforestation, fragmentation, urbanization, and agricultural conversion being among the leading factors” (40). His assessment seems to capture the essence of the problem: Insects are suffering from “death by a thousand cuts” (Fig. 1).

Taking the domesticated honey bee as an example, its declines in the United States have been linked to (introduced) mites, viral infections, microsporidian parasites, poisoning by neonicotinoid and other pesticides, habitat loss, overuse of artificial foods to maintain hives, and inbreeding; and yet, after 14+ y of research it is still unclear which of these, a combination thereof, or as yet unidentified factors are most detrimental to bee health.

Death by a thousand cuts: Global threats to insect diversity. Stressors from 10 o’clock to 3 o’clock anchor to climate change.

Featured insects:

- Regal fritillary (Speyeria idalia) (Center)

- Rusty patched bumble bee (Bombus affinis) (Center Right)

- Puritan tiger beetle (Cicindela puritana) (Bottom).

Each is an imperiled insect that represents a larger lineage that includes many International Union for Conservation of Nature “red list” species (i.e., globally extinct, endangered, and threatened species). Illustration: Virginia R. Wagner (artist).

Here are some other ways you can help by using your wallet as a weapon and joining the #Boycott4Wildlife

Contribute to my Ko-Fi

Did you enjoy visiting this website?

Palm Oil Detectives is 100% self-funded

Palm Oil Detectives is completely self-funded by its creator. All hosting and website fees and investigations into brands are self-funded by the creator of this online movement. If you like what I am doing, you and would like me to help meet costs, please send Palm Oil Detectives a thanks on Ko-Fi.

Palm Oil Detectives is 100% self-funded

Palm Oil Detectives is completely self-funded by its creator. All hosting and website fees and investigations into brands are self-funded by the creator of this online movement. If you like what I am doing, you and would like me to help meet costs, please send Palm Oil Detectives a thanks on Ko-Fi.