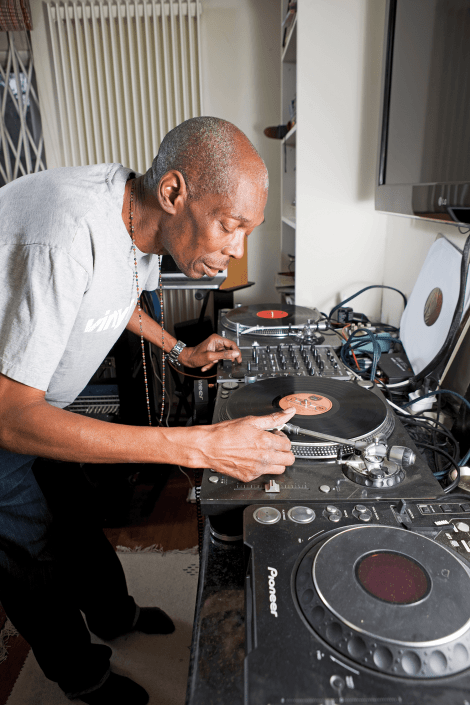

Gary Walker visited former Faithless frontman Maxi Jazz for a guided tour of the record collection that has soundtracked his incredible career in music

From humble beginnings in his childhood bedroom in Brixton, via the Soul Food Café soundsystem, a brief career as a pirate radio DJ and onto global success with Faithless, selling 15 million albums along the way, the sound of a stylus tripping across vinyl has soundtracked Maxi Jazz’s life.

The 59-year-old Buddhist, who now divides his time between his London home and a winter bolthole and studio in Jamaica, while giving his full musical attention to his new band Maxi Jazz & The E-Type Boys, is a self-confessed hopeless vinyl addict, with a collection of “between five and six thousand” records.

The obsession began to take hold one fateful afternoon in 1984, when The Soul Food Café was founded. “My brother came into my bedroom and said, ‘me and the lads have been talking…’ One of our mutual friends had a soundsystem at school, he had half and another guy had half, so we decided we were going to buy the other guy’s half out and start running the soundsystem on Saturday nights and play parties and stuff. That was the first step to me being here today.

“We bought out the soundsystem and started playing parties, and nobody would come because there were a lot of good sounds in our area – Touch Of Class, Funkadelic, Youthman Promotions for reggae, and Taurus. So getting people to come to your parties wasn’t easy.

Counter culture

Soundsystem DJ soon became radio DJ as Maxi, with a fast-growing collection of hip-hop vinyl, took to the airwaves with his Reach FM show In The Soul Kitchen With DJ Maxi Jazz, but that was far from the end of the story, as the young music fanatic began to experiment with making his own beats.

“I decided from there, ‘Why don’t we get onto the radio?’ Pirate radio was massive at the time – five or six different stations in London – and it was brilliant. I started to get onto pirate radio, and really that’s where the collecting thing started.

“When we played parties, you could go to a party and play the same 100 records and get away with it. On the radio, you can’t do that, you have to be finding new stuff and going to the record shop religiously, liaising with the people behind the counter and trying to find that good shit that you can play on the Tuesday night show on LWR or Reach FM or Star Point…

“From there, it was, ‘I’m playing hip-hop records on the radio and I’ve got all of the breaks that the producer used to make this record, but if I’d have made it I’d have put that there, and that over there and done that differently’, so that started to excite my interest.

“One of my favourite DJs ever is David Rodigan, and another is Emperor Rosko, for the same reason: they had the most fantastic jingles.

“So I determined that if I was going to be on the radio, I’d have some funky-ass jingles. I’d do pause-mixing to make jingles for my radio shows, and they’d be quite involved, so I got into this sub-industry of making jingles and adverts for other people on the radio station, at £25 a go. That was my introduction into making beats.”

The journey that led Maxi to international stardom with Faithless took another turn in 1989 when The Soul Food Café Band landed a record deal. Maxi takes up the tale: “I’d been collecting all these records, and I got this record deal from Tam Tam Records. I was making beats and I’d got together with this guy who worked in Strongroom Studios and wanted somebody to help him make a record, so off we went. Making beats was my thing and I was in my record collection all day looking for stuff. I had a lot of friends who were very good rappers, but they were young, too. So they’d come to my house, I’d give them a cassette of beats and I’d say, ‘Go and write some words and go and sell it’.

Three months later, you haven’t seen this kid, and either his girlfriend’s pregnant or he’s gonna have to go to court, or some bollocks is going on, and he hasn’t written the lyrics. So it was like, ‘If I don’t start writing some lyrics here I’m never going to get anywhere’, and that’s why I started writing words.

“When I discovered hip-hop, particularly Straight Out The Jungle by The Jungle Brothers, I realised I could make hip-hop, too, and write lyrics. Mike D and Afrika Bambaataa… their lyrics are playful, funny, intelligent and wise, and all that stuff I realised I could do. I realised there was a niche I could at the very least pop my toe into.

“Jive Records was massive to me. Two of my favourite bands were on Jive – KRS-One and A Tribe Called Quest, and every time I heard of a KRS-One beat out there, I’d leap up immediately and go and find it. It was his golden era, and everything he made was brilliant. My favourite rapper of all, though, is J-Live. He’s the cleverest, most insightful and incisive rapper on the planet today.”

After Maxi had founded his own record label, Namu, in 1992 and The Soul Food Café had toured with major acts including Jamiroquai, Soul II Soul and Jason Rebello, releasing the album Original Groovejuice Vol. 1 along the way, The Soul Food Café disbanded, paving the way for the formation of Faithless in 1995.

My first record

Despite having over 5,000 records in his collection, amassed over the past five decades, Maxi has no problem recalling his first purchase.

“I absolutely remember the first record I bought,” he says. “It was a major revelation. I listened to the radio religiously and it never occurred to my young mind that those songs you heard on the radio, you could go to the shop and buy them. When it occurred to me that’s what you could do, I went to the record shop with my seven and six in hand to buy Layla by Derek And The Dominos.

“I loved the guitar part, it really moved me. It’s amazing, it’s the simplest things that sometimes just resonate with people. A lot of the jazz records I love, with extremely technical, highly accomplished players, it’s just the simple little riff that drags you from wherever you are into that space.”

“I made jingles and adverts for other people on the radio station, at £25 a go. That was my introduction into making beats”

Hydepark cornered

When touring, Maxi’s downtime between gigs was used to scour the world’s record shops. “One of the best things that happened to me were those early days in Faithless,” he remembers. “You’d rock up in a town, you might have two days there, and the first thing you do is leave your room, go down and see the concierge and say, ‘Right, where’s the funky part of town with the record shops?’. The three of us would wander off, and find a record store, and hours later come out with armfuls of vinyl that you couldn’t find in the UK anymore.

“In Christiania [an autonomous commune in Copenhagen]… there’s a guy called DJ Hydepark, a reggae DJ who must be 6ft 7in tall. He’s sold me some of the best reggae music I have in my collection. I’ve gone into his shop and said, ‘I know you won’t have it, but…’ He’d say, ‘Let me have a look-see’, and you’d hear this voice echoing from the room behind the counter, saying, ‘Do you believe in miracles?’ And he’d come out not only with the 7″ of the song I want, but two other versions by different artists, and I’d say, ‘I love you man!’. Switzerland has always been great for buying records, Germany, too. Zurich had this record shop opposite the venue Faithless played. I’d started that tour by forgetting my wallet, so the tour manager was having to look after my expenditure until we got back home.

“I went into the production office and said, ‘Tommy, there’s a record shop right across the road, I need some money’. So he got all avuncular, and got out his big old Filofax and handed me a 50-euro note. I looked him dead in the eye and said, ‘And the fucking rest!’. He asked how much I wanted, and I said, ‘We’ll start with 400 euros!’.

“I took the 400 euros, went into the shop and it was an absolute treasure trove… After three hours, I went back into the office and said, ‘Tommy, I need some more money!’. He said, ‘How much do you want?!’. ‘Another 500!’. We almost had to hire another truck to get it all home!

“The worst thing is when you’ve got 70 quid and you go to the local record shop and find 80 quid’s worth of really good records, so 10 quid’s worth of music has to stay in the shop – which records are you leaving behind? These are some of the worst moments I’ve ever had, and I swore to myself, ‘Maxi, if you ever make a proper living at this music business and you’ve got money in your pocket when you get to the record shops, liberate EVERYTHING’.”

With 5,000 records lining the walls of his London house, Maxi finds it hard to pick a most valuable piece. “I’m not sure what the most valuable record in my collection is, but off the top of my head, another one I got from DJ Hydepark, and there’s a bit of a story attached to it… It’s a Frankie Paul record called Worries In The Dance, with Sugar Minott on the other side. I remember Rodigan playing this tune once, and he was so excited to play it. He put it on and said, ‘Oh my God, I’ve played the wrong side!’. He whipped the needle off, turned it over and on came this amazing, awesome tune with a bassline from hell. So we were leaving Copenhagen and stopping off at Christiania to get supplies… I was standing by the bus, surveying the scene and there was this old Danish caravan with a bunch of records for sale, and there was tune after tune after tune.

“I found this Frankie Paul record, turned it round, gave it to Hydepark and said, ‘Would you play this for me?’ and he put on the wrong side, and that’s when I knew I had the right record – both sides have the same label on, saying ‘Frankie Paul’! I’ve never seen another one before or since, and I honestly think if it got stolen or I lost it, or it got broken, that’s that…”

Maxi was a regular face in the 80s club scene in London, feeding his deep love of hip-hop, soul, reggae and dub on dancefloors across the capital and searching for new beats. He admits to feeling alienated at the onset of acid house.

“I grew up with 80s warehouse parties. You come out of a club and there are these dodgy looking blokes in green bomber jackets handing out these really cool flyers. You’d jump in the car and off you’d go. They played everything. Reggae, brand new hip-hop, old hip-hop, everything. That’s what I grew up with – people who can work a massive crowd with all kinds of music.

“Acid house came along, and I was astounded. That was Sister Bliss’s reformation moment, but I remember when there was a place in London for the music you wanted to hear on any given night, be it Cuban, reggae, whatever. When acid house arrived, if you didn’t like acid house, stay the fuck at home! My city had been overtaken by aliens!

We used to go Heaven on a Thursday night. There was a girl called Vicky Beats who played hip-hop. From 11 o’clock, the house music started in the main room, but upstairs was Patrick Forge and Gilles Peterson.

“It took years before London regained its true nature, and now thankfully, again, you can go and find enough wonderful types of music rather than just one thing.”

“I grew up with warehouse parties…people who could work a massive crowd with all kinds of music”

Top of the shops

Maxi’s quest for new material to spin on his radio show took him to all corners of the capital, and some of the record shops he visited back in the mid-80s remain favourite haunts today. “There was a shop in Elephant and Castle and I used to go there in my lunch hour, and there was one by Soho Square, a fabulous place… Honest Jon’s in West London – I still go there…Resolution Records in Brixton, because it was just round the corner from me. There were loads… I used to travel miles. I remember trying to get hold of The Beastie Boys’ first album when that came out. I don’t know how much petrol I must have put in the car to get that album, I went from shop to shop and was in central London before I knew where I was. Eventually, I found one shop that had one copy left! My favourite shop at the moment is my local one, the West Norwood Book And Record Bar, right at the bottom of my road. They’ve got a nice collection of old records.”

Change our destiny

Maxi continues to DJ himself, recently playing a string of dates in Ireland. However, his primary musical focus is now new band the E-Type Boys, in which he plays guitar and sings. Debut album Simple… Not Easy was released last summer and the band recently played a three-night run at the legendary Ronnie Scott’s in London. “It’s amazing, I can’t really describe it,” says Maxi, radiating positivity. “It’s so new, and so thrilling. Given that I’ve been a rapper and beat maker for the last 30 or more years, to not go first of all to my record collection if I’m feeling creative for loops, but to pick the guitar up and look for a chord, a progression or a melody – knowing that you can maybe finish it off and make it into something – is so thrilling. It comes directly out of you, filtered through nothing. It comes from that essence of you, and it feels more personal and special.

“If you’d said to me 10 years ago, ‘Maxi, you’ll be fronting your own guitar band, playing your own songs…’ 11 years ago, I wrote my first song and thought ‘Okay, well that’s a one-off, great,’ I never thought I’d make a career out of it, I’d have laughed in your face. “We played at Ronnie Scott’s, and they were three of the best shows I’ve played in my life. You have to impress at Ronnie’s – we got a standing ovation every night and on the last night, we were forced to play an encore, which is not allowed. And people were dancing, which is not allowed, and making videos, which is absolutely verboten!”

“It’s like when you’re just not that guy anymore, you know?” Maxi adds when asked whether this is the definitive end for Faithless. “Faithless was this wonderful thing that we managed to create and sustain for quite a while, but I don’t write rhymes over beats anymore. I’ve got this fascination with guitar and how much stuff you can bring out of yourself. I’ve got two albums’ worth of songs, and there’s more to follow, and now it’s just about ‘I wonder where this is taking me?’.”