Most people haven’t really heard of Eileen Agar. If they have, they’re probably nerds into niche British Surrealist art, or have studied Art History at uni. Or they are like me, who first came across Agar at the White Cube exhibition Dreamers Awake in 2017, then bumped into her again as part of a Lee Miller retrospective at the Fundació Joan Miró in Barcelona in 2019, and have had an artwork by her as my phone wallpaper for the past four years.

She’s easily one of my all-time favourite artists, and as a huge fan I had big expectations for the Whitechapel Gallery exhibition Eileen Agar: Angel of Anarchy. I was not disappointed.

The show is wonderfully curated, focusing (rightly) on the richness of Agar’s artistic output, spanning seven decades and flirting with movements including Surrealism, Cubism and abstraction. The fact that she takes the freedom to experiment with two, or more, of them at the same time gives her art its unique and unforgettable quality. This, coupled with her ability to draw inspiration from all kinds of sources – from classical mythology to found objects, and from costal rock formations in Brittany to the work of Braque and Picasso – makes of Agar a true artist.

Eileen Agar, Self-portrait: Eileen Looking Out (1935)

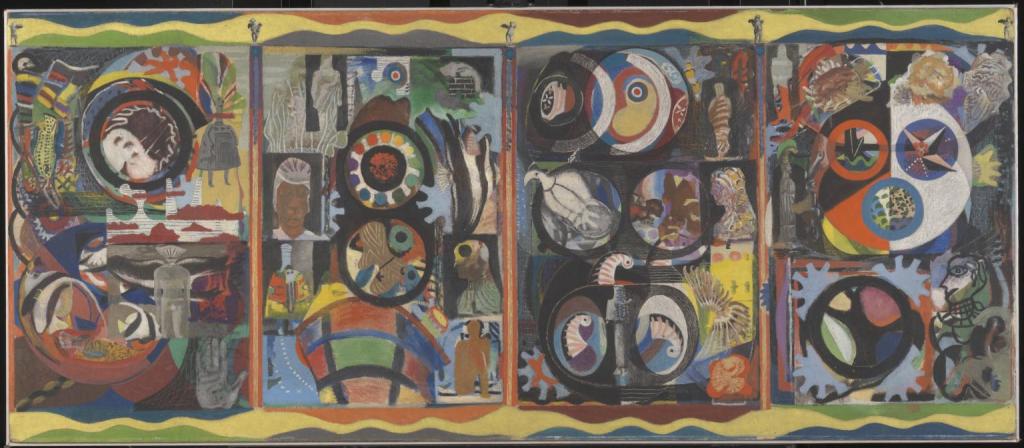

Remarkably, Agar was the only British female artist featured in the First International Surrealist Exhibition at the New Burlington Galleries in 1936. The works selected included ‘Winter’ – an evocative mélange of fluid lines and icy colours – and the masterpiece ‘Quadriga’ – a painting that is at once balanced and explosive, colourful and meditative, inspired by a scene in the Apocalypse and with four horsemen symbolising the rise of Fascism. From very early on she sets the tone for her artistic career: an indefatigable pioneer, her imaginative freedom places her both at the centre of artistic movements, but rejects any strict categorisation.

Eileen Agar, Winter and Quadriga (1935)

Looking at works like ‘Autobiography of an Embryo’ or ‘Procession’, it’s hard not to be drawn into the canvas. It’s a magnetic feeling. Your eyes flick between the overall composition and individual details, trying to decipher what every single element means. Agar’s paintings are somewhat similar to open texture concepts (and here I should thank the person that introduced me to them). They are not just “vague”, they are structurally elusive, with the web of allusions extending beyond a set range of meanings. Interpretations vary not only from one viewer to the other, but also within the same viewer, as they approach the paintings at different points in time.

Eileen Agar, The Autobiography of an Embryo (1933-4)

With the coming of WWII, Agar’s art inevitably changes. As well as experimenting with photography, with some brilliant shots of rock formations on the French coast of Ploumana’ch, and collage, Agar continues with oil painting, but bearing the emotional weight of the war. She describes herself as “exhausted and humdrum, more dispirited than usual”.

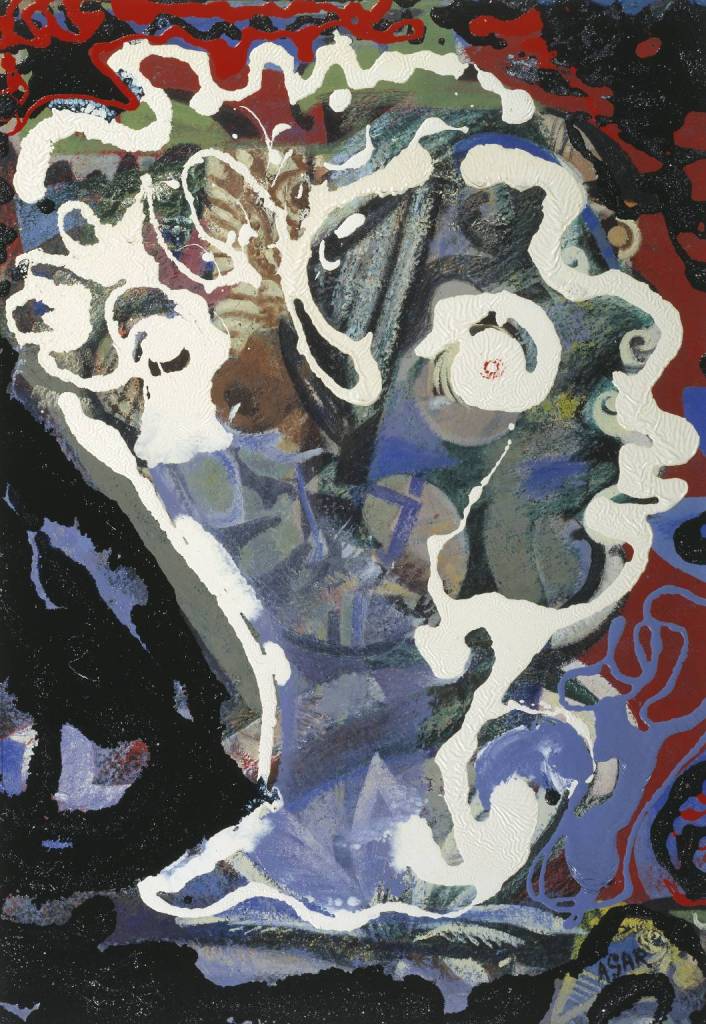

After the war, the curator mentions a transition to a “gentler pastel colour palette”, but, if anything, Agar colours seem to get more and more intense. In works like ‘Portrait of the Artist’s Mother’ or ‘Head of Dylan Thomas’ (painted seven years after his death), one can still detect the looming shadow of war. The Surrealist technique of automatism, or spontaneous painting, is here used in combination with dripping à la Pollock, tapping into the artist’s unconscious as well capturing as the personality of the sitter.

Eileen Agar, Head of Dylan Thomas (1960)

The last section of the exhibition was a personal favourite, as it brims with paintings inspired by classical mythology. ‘Maenad’, ‘Cleopatra’, ‘Orpheus and his Muse’ are only some of the gems on display. Here, Agar employs acrylic paint and large canvases to create some of her most striking works. Compositions are always rather tight, but the individual elements are arranged remarkably tidily.

Eileen Agar, Orpheus and His Muse (1959-60)

And once again, we see how Agar always felt comfortable walking between abstraction and Surrealism, between figurative and spiritual, and did so with her signature freedom. As she puts it: ‘I have spent my whole life in revolt against convention, trying to bring colour and light and a sense of the mysterious to daily existence. One must have a hunger for new colour, new shapes, and new possibilities of discovery.’