It was snowing heavily as we made our way from Highbury Corner to the Estorick Collection Gallery. London looked different, with colours drained to monochrome whites, blacks and greys. We were about to see an exhibition of work by the Italian artist Giorgio Morandi, whose paintings and drawings are characterised by a similarly reduced palette and an economy of line.

Drawing on a number of private collections, Lines of Poetry is an exhibition of almost 80 etchings and watercolours by the master of poetic understatement, Giorgio Morandi. Shy and retiring, and a man who lived a simple life, almost as spartan as his pictures, Morandi was entirely self-taught as a printmaker, but quickly mastered the technique and went on to be professor in the discipline for more than 20 years in Bologna. The subject matter of Morandi’s work may be restricted, but his still lifes and landscapes reveal his technical brilliance and, as de Chirico observed, the poetry in things that seem so familiar that we ‘often look upon them with the eye of one who sees but does not understand’.

This was the first time that I had visited the Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art, a small gallery housed in a Georgian house on Canonbury Square which celebrates its 15th anniversary in 2013. The gallery was founded by Eric and Salome Estorick, American art collectors who amassed a significant collection of modern Italian art, all of which was donated to the Foundation which now bears their name. The house in Canonbury Square was purchased in 1994 and refurbished to house the collection, along with an art library. Giorgio Morandi has proved to be one of the Estorick Collection’s most popular artists.

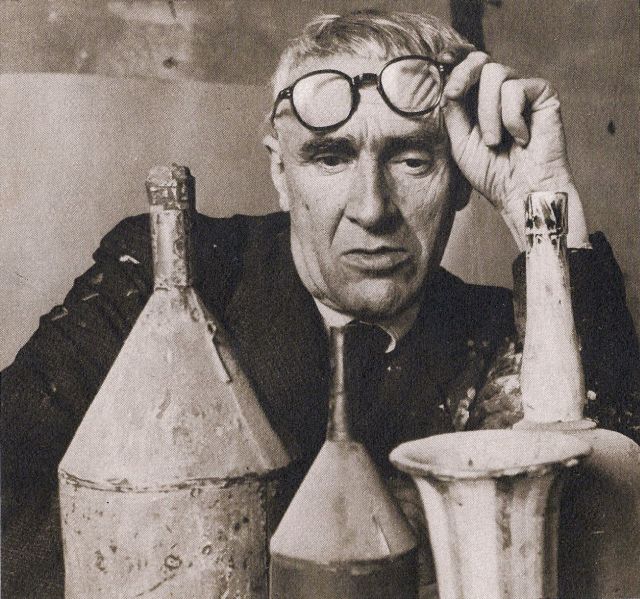

Giorgio Morandi was born in 1890 in Bologna, where he lived in the same house for the rest of his life, with his mother and three sisters. He worked and slept in a single room, surrounded by the dust-laden objects he portrayed in his paintings. Every summer, the family went to Grizzana, in the Apennines about 30 kilometres southwest of Bologna. Morandi himself said, ‘I have been fortunate enough to lead…an uneventful life’.

Morandi once spoke of spending his life in Bologna, ‘this town of the old university, the ancient towers, the arcades, the orderly, quiet, provincial atmosphere’. The house he lived in became his world. Yet he also lived through two world wars and through a period of social and political upheaval in Italy. He served in the army in the First World War and lived under German occupation in the Second World War.

Even though he lived his whole life in Bologna, Morandi was open to influences from other artists, including Derain, Picasso, and especially Cézanne. After a trip to Florence in 1910, he absorbed influences from past artists such as Giotto, Piero Della Francesca, and Paolo Uccello. He taught drawing in elementary schools from 1916-29, a period when he was briefly associated with the metaphysical painting movement, best known through the enigmatic still lifes of Giorgio de Chirico. After Mussolini came to power, Morandi’s closest ties were with the rustic Strapaese movement which advocated a return to local cultural traditions. In 1930 Morandi became Professor of Etching at the Accademia di Belle Arti, and his works began to be shown abroad.

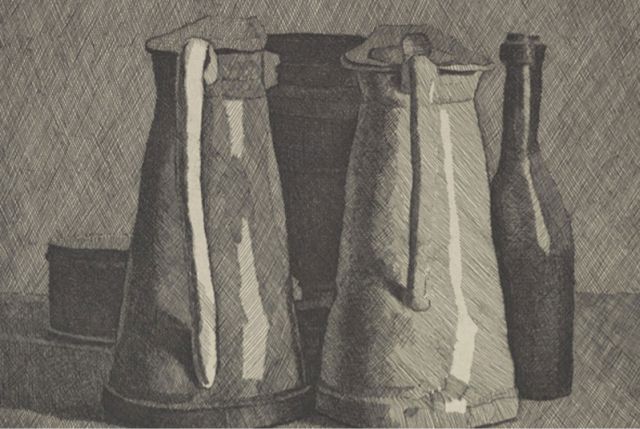

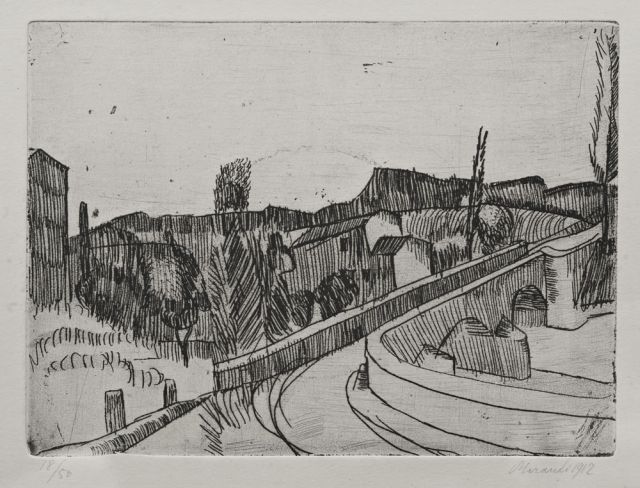

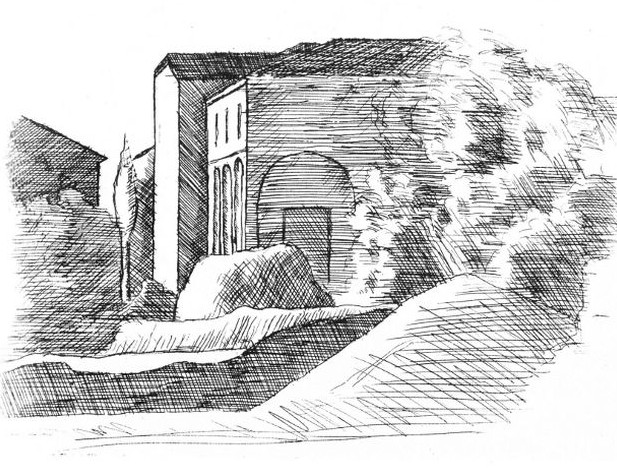

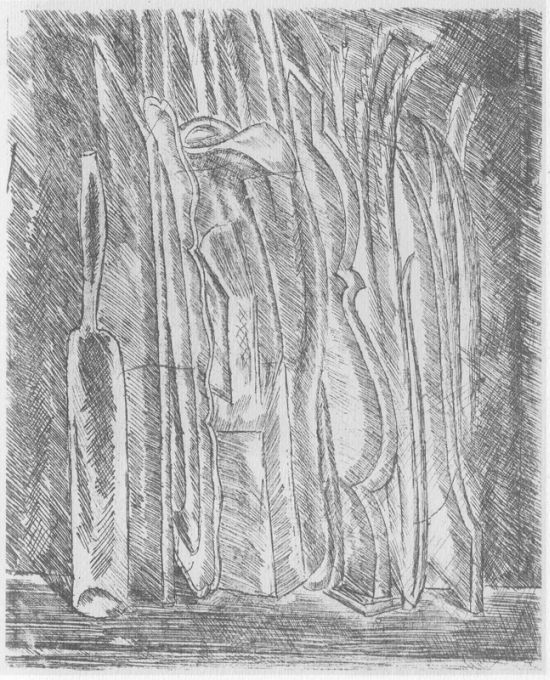

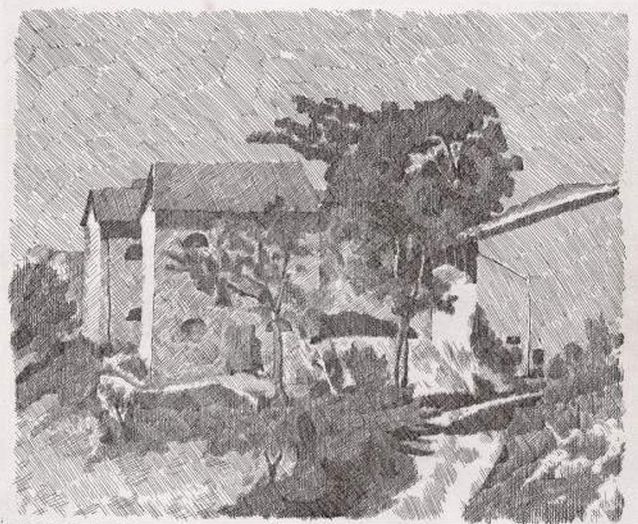

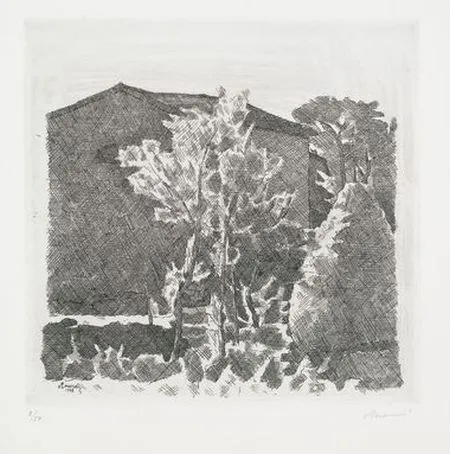

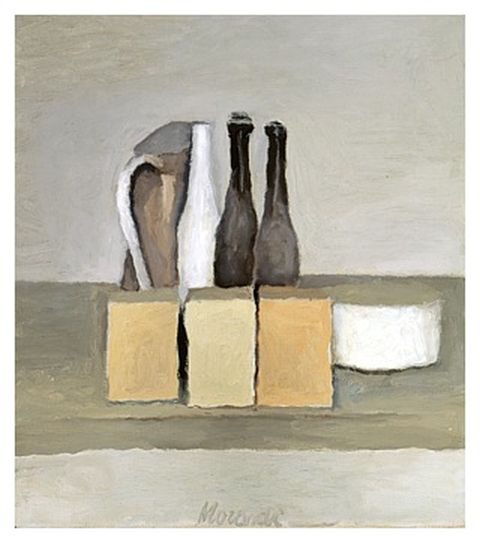

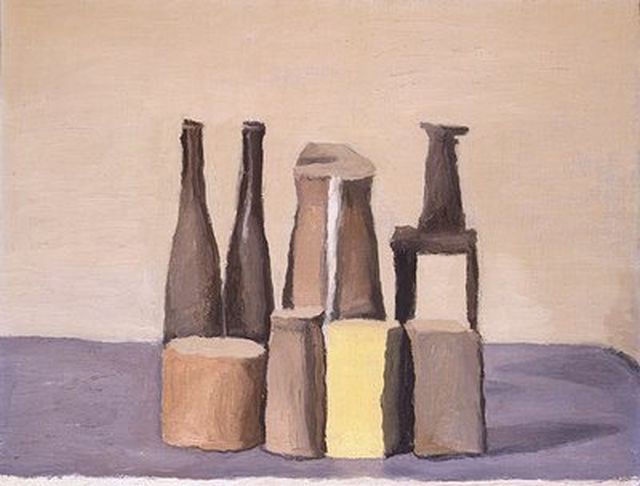

Lines of Poetry presents a chronological account of the artist’s development, beginning with his debt to Cézanne, as seen in an early etching such as ‘The Bridge on the Savena in Bologna’, a study of form in the landscape in which Cézanne can be seen as the model. A cubist phase follows in ‘Still Life with Bottles and Pitcher’ from 1915, but by the 1920s Morandi’s distinctive approach to composition emerges in a landscapes such as ‘Tennis Court at the Giardini Margherita’ and Landscape with Large Poplars (1927), in which Morandi seems to treat the lines of tall poplars as an element in an arrangement of forms in much the same way as his still lifes of of this period with their elongated forms .

There are two fine landscape etchings from this period, both views of his native Bologna in which areas of pure white are contrasted with thickly etched lines: ‘Landscape (The Chimneys of the Arsenal on the Outskirts of Bologna)’ (1927) is an industrial vista whose horizon is broken up by factory chimneys rising over suburban roofs, while ‘Three Houses in Campiaro, Bologna’ (1929) is a study of the rectangular shapes of the buildings contrasted with the softer, natural forms of trees and shrubs.

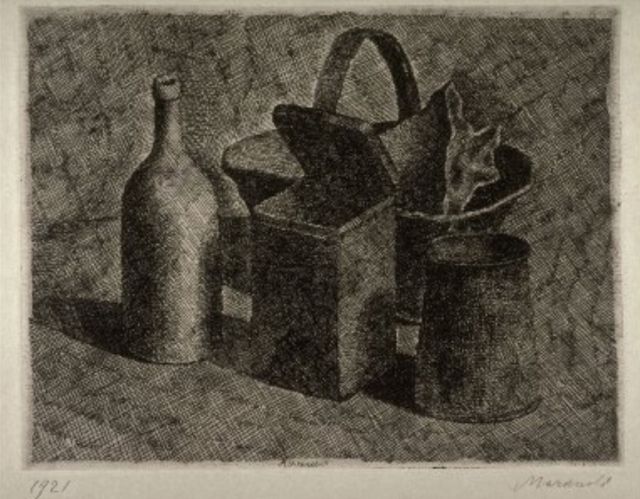

Here, too are three still lifes from 1921: ‘Still Life with Basket of Bread’ – with bottle, squat vase, open tin and basket depicted in deep shades of cross-hatching with the texture of cloth – and the exquisite ‘Still Life with Sugar Bowl, Lemon and Bread’ and ‘Still Life with Bread and Lemon’. They are simple, mysterious, and atmospheric. It around this time that Giorgio de Chirico wrote of Morandi:

We are not a people suited to growing complacent in bourgeois existence. The richest and most content of our bourgeoisie always have, at the bottom of their nature, something more unquiet and restless than the poorest peasant of more northerly and happier lands that are less warm and less bright. That this fatal melancholy sharpens our vision of the world is an undeniable fact. Italian art, in its more skeletally beautiful aspects is a hard, clean and solid thing. From such denuded forms, cleansed of unrestrained enthusiasm and improper joy, is born that chaste, austere and lofty spirit which represents the highest merit of our great painting from the primitives to Raphael. Today, the confusion which oppresses the arts is enormous; and the poor quality of the painting that floods the continents with torrents of greasy, oily colour is difficult to define. There is an abundance of foolishness, much lack of understanding, a great deal of banality and cheap sensuality – and as for spirit, one would search for it in vain.

Therefore, it is with sympathy and a great sense of comfort that we have followed the emergence, development and maturing of artists such as Giorgio Morandi through their slow but sure labours.

He seeks to discover and to create everything alone: patiently grinding his colours, preparing his canvases and looking at the objects that surround him, from loaves of ‘sacred bread’ – dark, and riven with cracks like the surface of an ancient rock – to the clean forms of glasses and bottles. He looks at a collection of objects set on a tabletop with the emotion that shook the heart of the traveller in ancient Greece when he gazed upon woods, valleys and mountains believed to be the realm of beautiful and surprising deities.

He looks with the eye of one who believes, and the innermost skeleton of these things – dead for us, since immobile appears to him in its most consolatory aspect: in its eternal aspect. In such a way he engages with the great lyricism created by the most profound European art: the metaphysics of the most commonplace objects. Of those objects that habit has rendered so familiar to us that we often look at them with the eye of one who sees but does not understand. … In his ancient Bologna, Giorgio Morandi sings in this way – in an Italian way – the song of the great European craftsmen. He is poor, since the generosity of art lovers has thus far eluded him. And in order to be able to continue with his work with purity in the evenings, in the bleak rooms of a state school he teaches youngsters the eternal laws of geometric design – the foundation of every great beauty and of every profound melancholy.

I love that line: ‘He looks at a collection of objects set on a tabletop with the emotion that shook the heart of the traveller in ancient Greece when he gazed upon woods, valleys and mountains believed to be the realm of beautiful and surprising deities’.

Morandi’s friend Raffaello Franchi later recalled visiting the house in Bologna:

I recall his house as it appeared to me the first time I saw it, divided into two parts – two worlds. In the first – neat and tidy, with a mirror sheen – lived his mother and sisters. In the second lived the artist with his work – and one could not call it dirty only because the thick dust that covered everything was the result of a religious respect for sacred things: the piece of dried bread on a stool, the mother-of-pearl shell he might have gathered … and the jug stolen from his mother’s kitchen …

From the late 1920s come several lovely etchings that evoke the landscapes around the holiday home in Grizzana: ‘Hillside in the Morning’ and ‘Hillside in the Evening’ (both 1928), and ‘Grizzana Landscape’ (1932). The art critic Luigi Magnani described Morandi as seeing Grizzana ‘wrapped in a halo of poetry’ where ‘large spaces were offered to his gaze: hills, meadows, forests … to Morandi it was blessed’.

Morandi gained international acclaim after the Second World War, rapidly becoming one of the most respected Italian painters. In 1956 he travelled outside Italy for the first time. Morandi’s high profile in Italy was shown when Federico Fellini’s featured his paintings as the epitome of cultural sophistication in La Dolce Vita in 1960. By this time, however, Morandi had withdrawn to work in his studio at Grizzana. He died in Bologna on 18 June 1964.

Morandi controlled every aspect of making a painting, from stretching his own canvases and making his paints (which meant he could maintain precise control over his palette), to placing his objects, lighting them and positioning himself before them. The objects he chose to paint – bottles, jars, jugs and cans – were placed on sheets of paper on specially made tables and shelves and their position marked out in pencil. He endlessly arranged and rearranged the same objects—bottles, tins, and boxes collected from the shops near his home—in search of new combinations and formal possibilities.

‘Nothing is more abstract than reality,’ Morandi declared. The restrictions of his subject matter and of monochrome etching forced him to focus on the relationships between objects, and between objects and light. He studied the beauty in small things.

It takes me weeks to make up my mind which group of bottles will go well with a particular coloured tablecloth. Then weeks thinking about the bottles themselves, and yet often, I still go wrong with the spaces. Perhaps I work too fast.

Josef Herman, a friend of Morandi, recalled visiting his studio:

The floor was by far the most cluttered part of the room; … littered with bottles, all different sizes, shapes and colours. I had no difficulty in recognising some of the bottles I had seen in Morandi’s paintings; only in the paintings they possessed a dignity and a life of their own … The live bottles had nothing of the kind. The nobility of the colours and the textures was obviously an invention of Morandi’s.

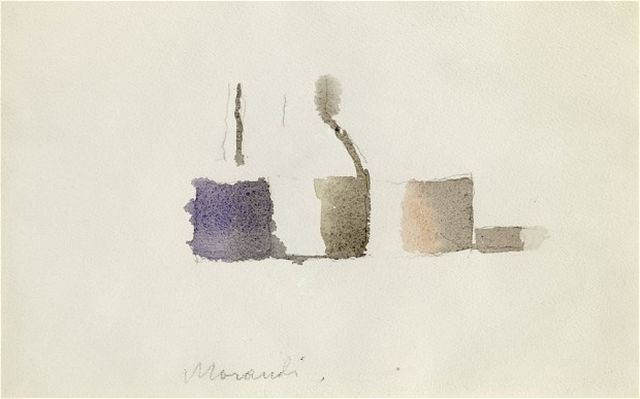

In Morandi’s still lifes of the 1950s and 60s, objects are reduced to near-abstraction: cylinder, cone, sphere. Like Cezanne, Morandi favoured the pared-down yet spontaneous medium of watercolour. A highlight of this exhibition is a group of rarely displayed watercolours in which less is more: a few barely discernible pencil lines and three quick smears of muted colour in ‘Still Life’ (1960), and fragile outlines bathed in shadow and light, just discernible as landscape in ‘Landscape (Levico)’ and ‘Landscape (House in Ruins)’ from 1957-58.

Giorgio Morandi may have lived a simple life, but he did not make simple art. He altered the colours of bottles, bowls and vases before arranging his still lifes. He played with shadows, scale and light. In a 1955 radio interview he explained: ‘I want to communicate those images and feelings that the natural world awakens in us.’ Three still lifes from 1955-56 (not in the exhibition) seem to bear this out:

Here are two trailers for the documentary Giorgio Morandi’s Dust, which is screened at the Estorick exhibition. It presents the life of Morandi through his still lifes and landscapes and the eyes of friends and critics.

Giorgio Morandi’s Dust – International Trailer w/English subs from Imago Orbis on Vimeo.

This YouTube video offers a slideshow of Morandi’s work.

We left the gallery to walk in Highbury Fields, with the snow still falling. We noted how everyone seemed to be smiling. Children on sledges, throwing snowballs and building snowmen. In fact, the snow seemed to have brought the artistic streak out in adults, too.

See also

- Morandi: Lines of Poetry: Guardian review

- Giorgio Morandi: Lines of Poetry: Telegraph review by Alastair Sooke

- Giorgio Morandi: The Essence of the Landscape

- Giorgio Morandi Highlights: extensive series of short video podcasts on works from each stage of Morandi’s career

Excellent review of Morandi’s work and this exhibition. Thanks for sharing this.

Reblogged this on Mississhippi's Madness and commented:

An excellent article about Morandi. a favourite artist of mine and a review of a current exhibition of his work. Wish I could see this one.