Mandy Moore and Leanne Prain celebrate ten years since the first publication of Yarn Bombing and reflect how it has defied the homely associations of knitting.

Each yarn bombing starts with a single stitch. But with imagination, it becomes so much more. For more than ten years, we’ve seen how yarn bombing resonates with people intellectually, spiritually, and emotionally. We’ve learned that yarn bombing can be an expression of love. It can be a monument to memory. It can be a simple experience of whimsy or a strong-willed political statement. It offers a window to the fantastical, inspires calls to action, and becomes a medium for storytelling. No matter what shape a yarn bombing may take, every act involves innovation and creativity.

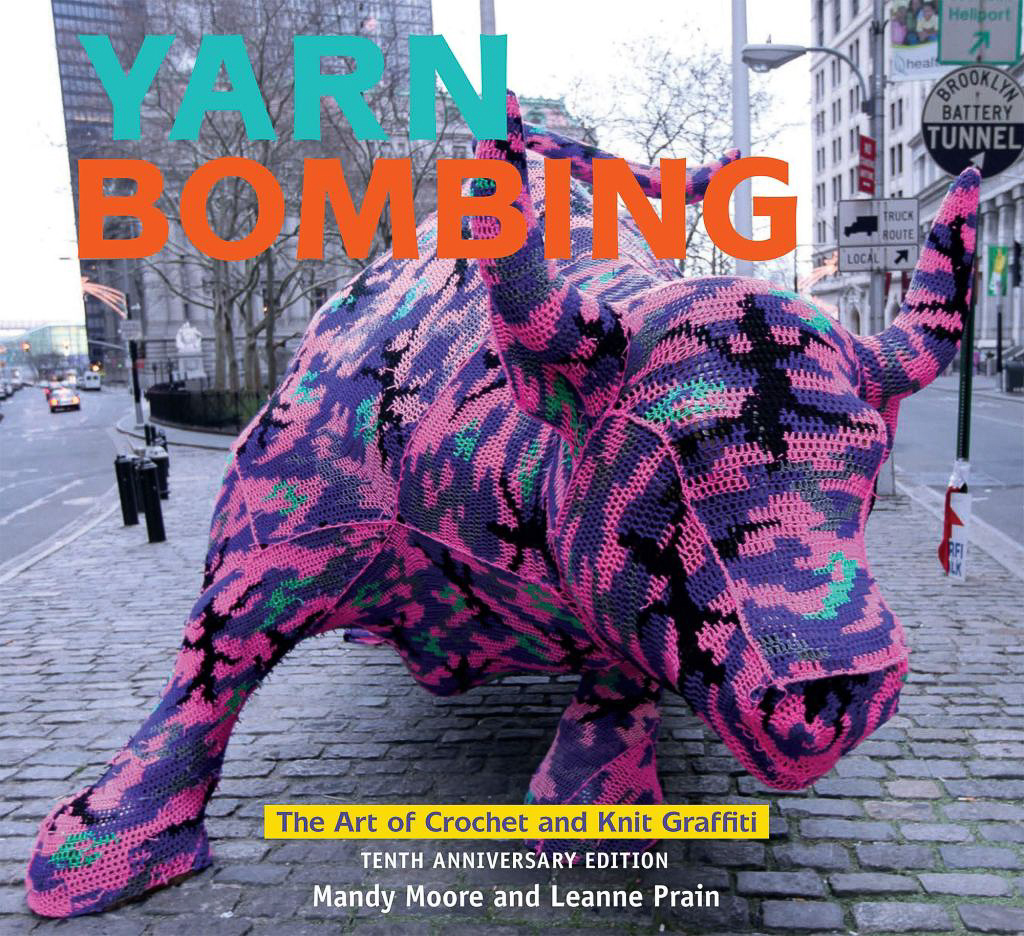

Our book Yarn Bombing: The Art of Crochet and Knit Graffiti was first published in 2009. When the book was released, we were overwhelmed by the enthusiasm that it received. Although we knew that crafters would be delighted by yarnarchy, it surprised us how quickly the book was embraced by other communities. We heard from landscape architects, art professors, youth groups, schoolteachers, graffiti removal services, politicians, and spray paint and wheat paste artists. Yarn bombing has become a catalyst for conversation around many topics, including the built environment, the purpose of art and craft, the juxtaposition of a “feminine” medium in a traditionally masculine context, and societal assumptions about the value of women’s work and time.

We’ve met yarn bombers who have created work around ocean plastic, suicide, gentrification, sexual assault, and equal rights, among other critical issues of our time. In each instance, these crafters have used their hand skills to engage diverse opinions, and their work has become a medium that invites discussion. The two of us have made work with ninety-year-old yarn bombers, and seven-year-old ones. We’ve heard from social workers using craft as therapy, advertising agencies looking to co-opt the movement, and academics trying to make sense of it all. We’ve heard about various rules that we’ve supposedly broken and folks that we’ve offended, while witnessing yarn bombing flourish and change both communities and individuals.

With roots in a thousand-year-old craft, yarn bombing is a hyper-local activity; thanks to our virtually-connected world, it’s a global one as well. As Hinda Mandell of the remarkable Jewish Hearts for Pittsburgh project attests, “We learned that something as simple and homey as yarn can be a catalyst for a social media community that is as supportive and loving as an IRL knitting circle. We learned, and were even surprised by, the extent to which the act of making could be a healing mechanism, and a channel for expressive love, in the face of hate and fatal violence. We were uplifted by the affirmation that people want to help, that people want to heed a call for action, and that craft provides an outlet for love-imbued productivity that is as much about providing comfort to self in unsettling times, as it is about providing comfort to a community that may be hundreds of miles away from the crafter.”

More than just grandiose fuzzy statements, yarn bombing is about being seen. Craft is a slow process. Being a knitter or crocheter means that you are willing to invest time, materials, and skill in making something. Being a yarn bomber means that you are intentionally creating work that might only last in public for minutes before it is taken down. There’s a magic in this kind of gift-giving—the act of making a yarn bomb is a testament to experimentation and being free.

As Magda Sayeg, the godmother of yarn bombing, has said, “Yarn bombing means putting yourself and your work out in the public environment. Even if it gets taken down or vandalized, at least people saw it when it was up, and that’s a good enough reason to have done it in the first place.”

In our first attempts at yarn bombing, we created little tags that we wrapped around poles and trees on Robson Street in downtown Vancouver, Canada. At that time, our city was just beginning to transform in preparation to host the 2010 Olympic Games. Little did we know that the local shopping district we were tagging would transform into a row of the same luxury stores that a shopper could find in any city in the world. As globalization expands, the ability to make something with your hands that can’t be replicated by any machine or commercial entity becomes even more meaningful. Yarn bombing becomes what craftivist Betsy Greer has called a love letter to cities. What we make by hand, and our reclamation of the ability to construct our own objects and culture, is a political act in a global society that insists on striving for homogeneity.

Those who devote themselves to yarn graffiti are curious people, they have a sense of humour and a sense of justice. Yarn bombers belong to a special tribe of people—those who want to make a difference, who are unafraid to challenge the norms of where craft belongs and what it can do. We are in awe of makers who continue to push the limits of what can be done with a few skeins of yarn and some simple tools.

At the center of the yarn bombing movement is Magda Sayeg, the godmother of knit and crochet graffiti. From her humble beginnings wrapping a stop sign pole with a simple tag to becoming a sponsored pro yarn artist, Magda has continued to push the envelope of how yarn, the urban environment, and the art world intersect. From handling major public commissions with the likes of Comme des Garçons and Mini Cooper, to showing her art in New York galleries, to rallying communities to create massive public art projects, and then still tagging for her own delight, Magda has continued to redefine public space with her use of yarn.

We reconnected with Magda in May 2019, when she was planning her most ambitious art project yet: covering the Williamsburg Bridge in Brooklyn.

Excerpt from an Interview with Magda Sayeg, April 2019:

Mandy and Leanne: It has been interesting to see yarn bombers go in many different directions over the last ten years—from street art to galleries to complete political protest. It feels like yarn bombing has evolved rapidly as our world has changed.

Magda: I think it’s interesting how many people want to put you in a box, and I don’t want to be put in a box. I want to do creative stuff. I absolutely love knitting, but don’t make me do only yarn bombing, you know? In order to be engaged, you have to do something different from what you’ve done before, which is uncomfortable.

Craft is still kind of like the “Hey Grandma”—the lowest regarded art form. It shouldn’t be—because it’s more meaningful and functional [than other forms]. I experience this interesting observation like, Oh, wow, because I’m working in yarn, you don’t think I’m a real artist. People who see it that way are missing out, because this art is incredible.”

Mandy and Leanne: The pussyhat, love it or hate it, making the cover of Time magazine in 2017 was such an interesting cultural moment. In the first edition of this book, we included an image of the cover of Seattle’s independent paper The Stranger when it featured Erika Barcott’s Treesweater, which was considered such an oddity at the time. So much has changed.

Magda: Knitting is so strongly associated with women, and the domestic, and you know, [women’s] existence. It’s so funny that society undervalues it. Knitting made the cover of Time, and there’s a reason for that—it’s potent.

Craft doesn’t have to be precious and homey. It can be badass. It can be street art. Of course, people instantly want to criticize it because of the expectations that graffiti should be male-dominated. Why do we need to be like the existing art scene—why can’t we just be more like us, than like them?

I like to stay true to the spirit of yarn bombing: it is something you do, unsanctioned, without permission, on the streets. You don’t care if it gets taken down; you’re part of urban culture.

I couldn’t knit a sweater to save my life—but to see knitting in a different light, enhancing the ordinary and changing inanimate objects, is so powerful. But even beyond that power, the fact that a stranger can walk by it and smile. Wow. that’s enough to make me happy.

An excerpt from Yarn Bombing: The Art of Crochet and Knit Graffiti (Tenth Anniversary Edition), published by Arsenal Pulp Press in 2019.

Authors

Yarn Bombing: The Art of Knit Graffiti was first published by Arsenal Pulp Press in Vancouver, Canada 2009. It was republished with a new ten-year anniversary chapter and new preface by the authors in 2019. Mandy Moore has worked in the yarn craft industry since 2001, as a teacher, designer, and technical editor, as well as in retail. You can find her on Instagram at @yarnageddon. Leanne Prain is the author of Hoopla: The Art of Unexpected Embroidery and Strange Material: Storytelling Through Textiles, both published by Arsenal Pulp Press. (leanneprain.com).

Yarn Bombing: The Art of Knit Graffiti was first published by Arsenal Pulp Press in Vancouver, Canada 2009. It was republished with a new ten-year anniversary chapter and new preface by the authors in 2019. Mandy Moore has worked in the yarn craft industry since 2001, as a teacher, designer, and technical editor, as well as in retail. You can find her on Instagram at @yarnageddon. Leanne Prain is the author of Hoopla: The Art of Unexpected Embroidery and Strange Material: Storytelling Through Textiles, both published by Arsenal Pulp Press. (leanneprain.com).