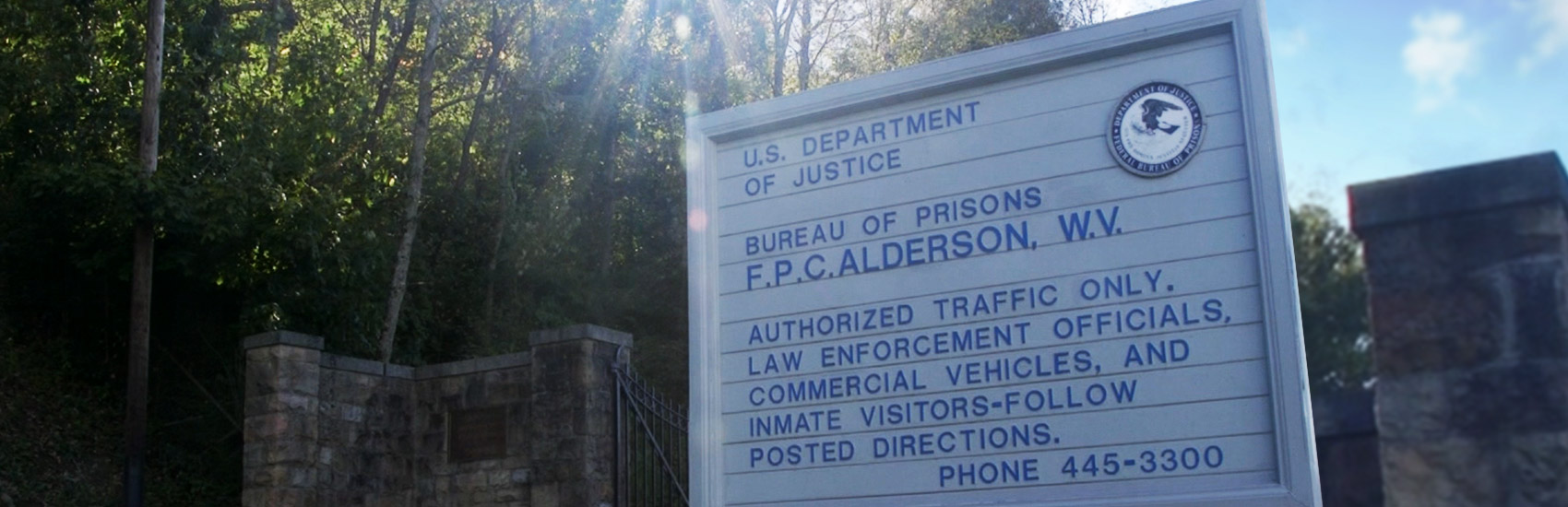

A chilly predawn fog envelops the Greenbrier River as it meanders among the mountains of southeastern West Virginia. On the outskirts of the tiny village of Alderson, the river’s water courses through a large horseshoe bend that wraps around three sides of the Federal Prison Camp for Women. Inside, more than a thousand inmates have just finished breakfast.

On the street outside the prison’s main gate, a group of siblings in their twenties nervously mill around, watching over their brood of young children. They keep peering through the fog, looking down the road inside the gate. The sounds of a coal-bearing train on the tracks that hug the inside of that river bend float through the moist air.

Suddenly, a white sedan rolls slowly through the gate, coming to a stop on the side that signifies freedom. A woman dressed in a grey sweat suit, the uniform all prisoners wear here, springs out of the back seat with a huge smile.

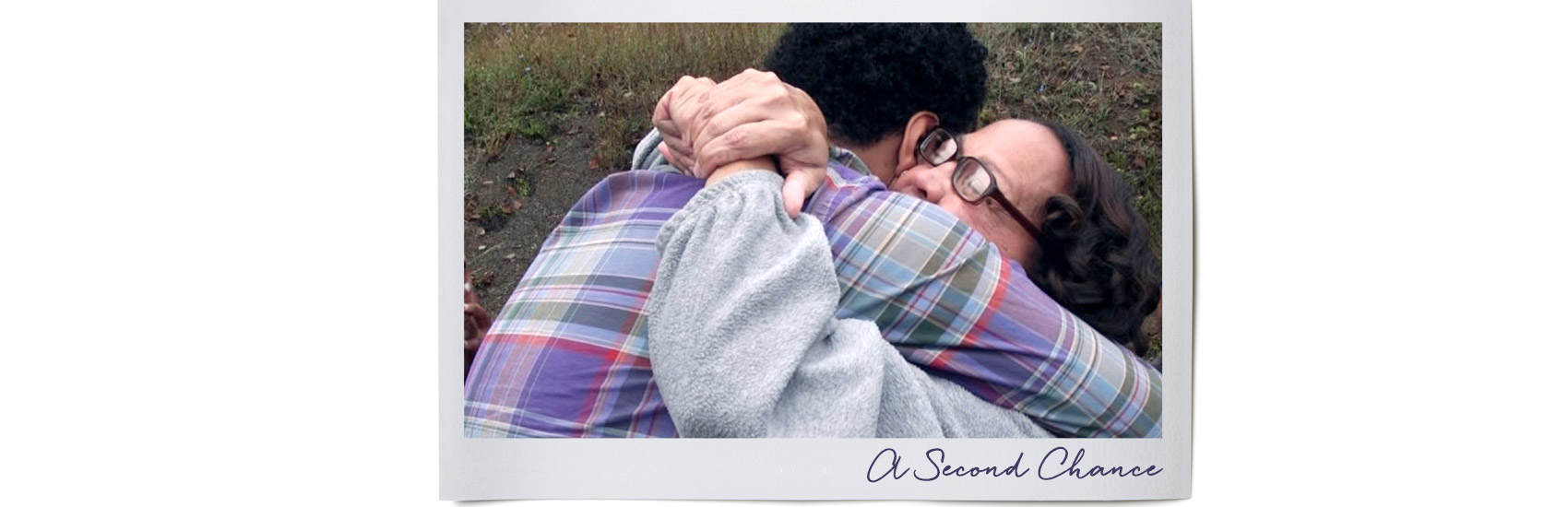

“Momma!” yells Barry, one of her waiting sons, as he runs toward her.

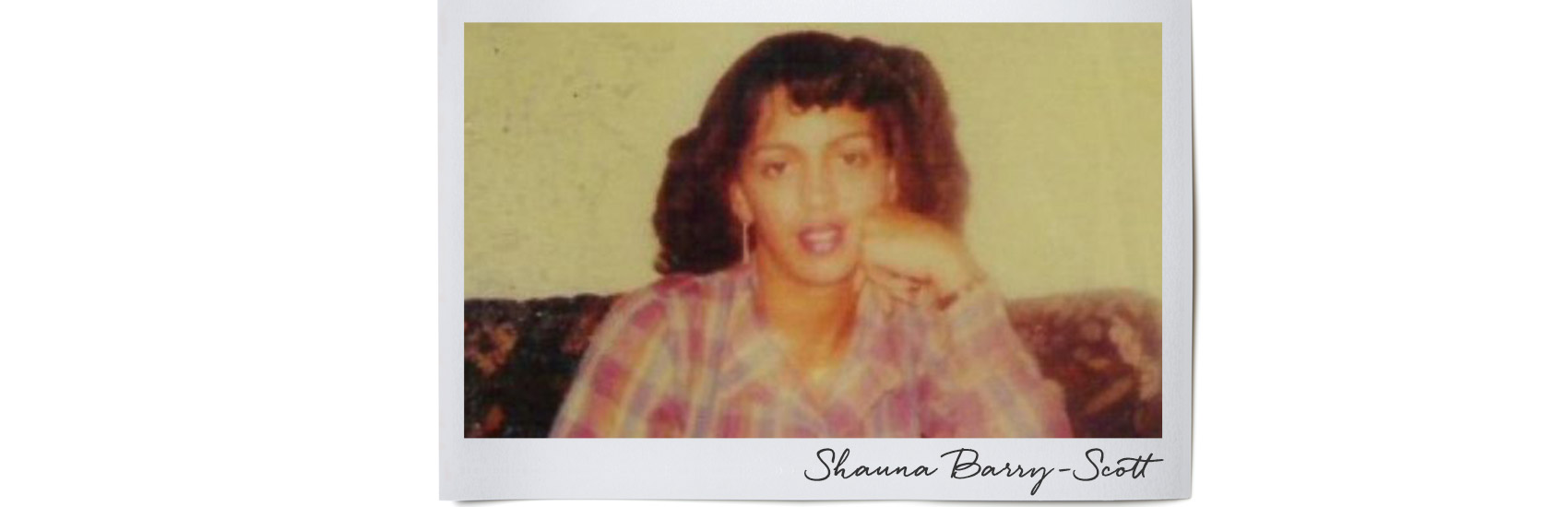

He embraces the 53-year-old woman tightly as the others surround them. “My baby!” she says, as tears of joy flood the scene. The nearby train whistle swallows their happy laughter. For the first time in more than a decade, on this mid-September morning, Shauna Barry-Scott is free.

On the street outside the prison’s main gate, a group of siblings in their twenties nervously mill around, watching over their brood of young children. They keep peering through the fog, looking down the road inside the gate. The sounds of a coal-bearing train on the tracks that hug the inside of that river bend float through the moist air.

Suddenly, a white sedan rolls slowly through the gate, coming to a stop on the side that signifies freedom. A woman dressed in a grey sweat suit, the uniform all prisoners wear here, springs out of the back seat with a huge smile.

“Momma!” yells Barry, one of her waiting sons, as he runs toward her.

He embraces the 53-year-old woman tightly as the others surround them. “My baby!” she says, as tears of joy flood the scene. The nearby train whistle swallows their happy laughter. For the first time in more than a decade, on this mid-September morning, Shauna Barry-Scott is free.

It was just after the turn of the millennium. Barry-Scott, had sold crack cocaine, a drug that an estimated 6.2 million Americans had smoked. “It’s really kind of hard to explain if you don’t come from our world,” she says, as she struggles to explain why. “Drugs are so prevalent and so commonplace that it’s really nothing unusual. It’s just kind of a regular part of life.”

Barry-Scott lived in Youngstown, Ohio, a rust belt city situated in the nether-region between Cleveland and Pittsburgh. When America’s steel companies collapsed in the 1970’s, some 40,000 well-paying jobs left Youngstown. Population and affluence went with them, and the resulting vacuum was filled by poverty and drugs.

Shauna had fallen into that crevasse. But she was clawing her way back up. The mother of five had put drugs behind her, gotten a job, and was often working 12 or more hours a day. The drug world has a way of pulling people back in, though, and for Shauna that tug came from a friend.

“Someone who I really, really trusted convinced me to get some drugs for them,” she explains with a heavy sigh. “And he was working for the police. He was in some trouble and he wanted to get out of his trouble. And I just, you know, fell for his ploy.”

After the man bought crack from Barry-Scott three times, police executed a search warrant on her home. Inside they found some crack packaged for sale and cash. Some of the bills were the ones the police had given the informant. It was 2005, and the federal mandatory sentences for drug-related crimes were harsh. When the judge sentenced Barry-Scott, a non-violent offender, to 20 years in federal prison, she was “shocked.”

“I think I was just stunned,” she says. “It didn’t really dawn on me what happened until later that night.”

The sentence was particularly stinging because her oldest son had been murdered on the streets of Youngstown just three years earlier, shot multiple times by two assailants. They received sentences so short that Barry-Scott’s children would see the two men who murdered their brother walking the streets of Youngstown, while their mother sat in Federal Prison Camp Alderson.

After the man bought crack from Barry-Scott three times, police executed a search warrant on her home. Inside they found some crack packaged for sale and cash. Some of the bills were the ones the police had given the informant. It was 2005, and the federal mandatory sentences for drug-related crimes were harsh. When the judge sentenced Barry-Scott, a non-violent offender, to 20 years in federal prison, she was “shocked.”

“I think I was just stunned,” she says. “It didn’t really dawn on me what happened until later that night.”

The sentence was particularly stinging because her oldest son had been murdered on the streets of Youngstown just three years earlier, shot multiple times by two assailants. They received sentences so short that Barry-Scott’s children would see the two men who murdered their brother walking the streets of Youngstown, while their mother sat in Federal Prison Camp Alderson.

After more than 10 years of confinement, President Barack Obama saw fit to commute her sentence this past July. She’s one of 79 Americans granted clemency in 2015 for low-level drug offenses that landed them in prison for decades of their lives. Of the 3,293 pleas for clemency the president received this year, Barry-Scott’s was one of the few he approved.

Read more: What Powers Presidents Have to Set Prisoners Free

Clemency for Barry-Scott comes as the Obama administration implements a sweeping overhaul of sentencing guidelines set into motion in 2014. After careful judicial review of individual cases, thousands of federal prisoners sentenced under old drug laws are now seeing their sentences reduced.

Around early November 2015, roughly 6,000 federal inmates will be released from custody. Many have already been moved to halfway houses and home confinements, though the vast majority will remain under the supervision of the U.S. Probation Services.

Read more: What Powers Presidents Have to Set Prisoners Free

Clemency for Barry-Scott comes as the Obama administration implements a sweeping overhaul of sentencing guidelines set into motion in 2014. After careful judicial review of individual cases, thousands of federal prisoners sentenced under old drug laws are now seeing their sentences reduced.

Around early November 2015, roughly 6,000 federal inmates will be released from custody. Many have already been moved to halfway houses and home confinements, though the vast majority will remain under the supervision of the U.S. Probation Services.

Clemency has given Barry-Scott a second chance at life in Youngstown, Ohio, home to her 4 children and 17 grandchildren. But hundreds of thousands of Americans who committed similar offenses yearn for the same, still looking at the outside world through razor wire and bars.

Seventy-nine percent of non-violent offenders serving sentences of life without parole are there for drug crimes, according to a 2013 ACLU study. Some, like Ronald Evans of Norfolk, Virginia, were arrested for drug offenses committed before they were even adults. He became involved in the drug world at age 15, earning $50 a day after school as a street-corner lookout for local drug dealers. Eventually, he transported money and drugs, and sold heroin to addicts. Ronald, now 43, has spent his entire adult life in prison and unless his sentence is commuted, he will die there.

More about Evans story: Crying for Clemency: A Life Sentence for Drugs

The U.S. is home to 5 percent of the planet’s populace, but it also holds 25 percent of the world’s incarcerated population. The 2.2 million Americans behind bars is far more than are imprisoned in any other country on the planet. Three hundred thousand are serving time for drug offenses. In federal prisons alone, almost half of all inmates are serving time for drugs, according to the U.S. Department of Justice.

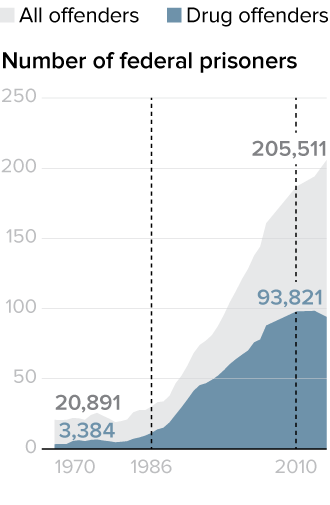

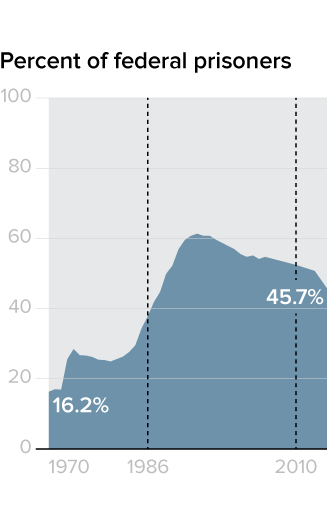

When the ill-fated “War on Drugs” was launched 29 years ago, the campaign swept up hundreds of thousands of Americans and put them in prison. The Anti-Drug Abuse Act signed by Ronald Reagan in 1986 codified a mindset of “Just Say No to Drugs,” a mantra that inspired a movement toward harsher punishment as the best deterrent to the sale and use of illicit drugs.

NOTE: Federal prisoners only includes the sentenced population.

SOURCES: U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Prisons, Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics

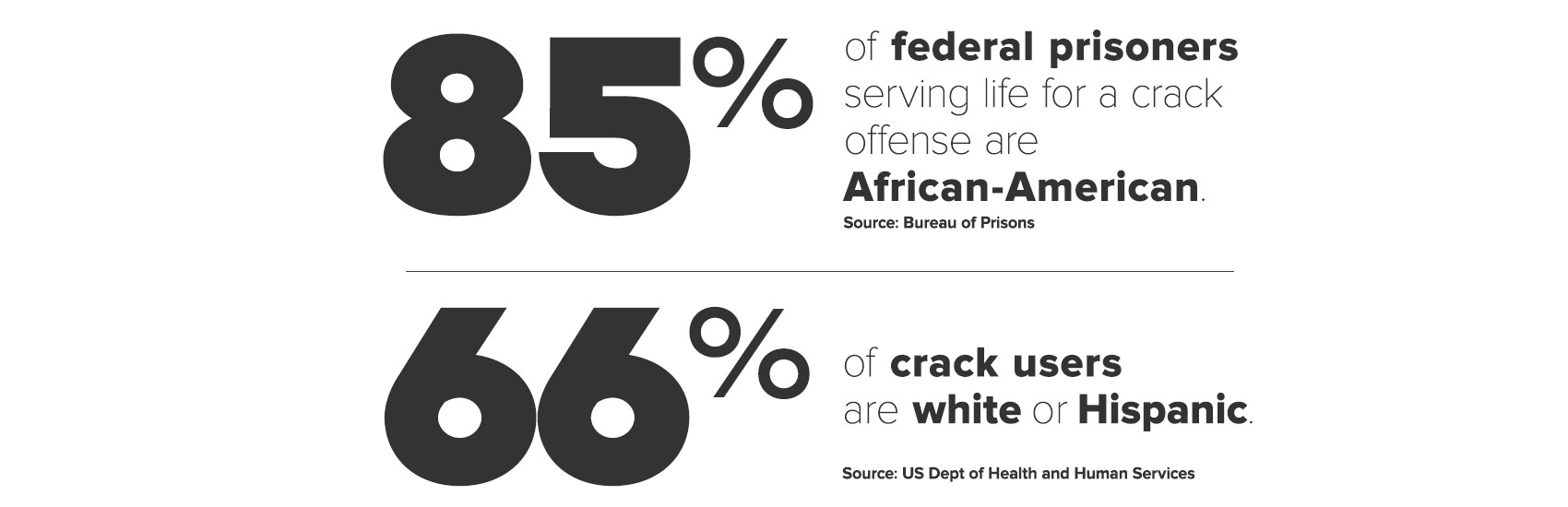

Mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses took judges out of the equation. No longer would they have the discretion to send low-level offenders to drug treatment programs, as was the common practice prior to this Act. The law took direct aim at crack cocaine, under the misguided belief that it was a far more dangerous substance than cocaine in its powder form. The Anti-Drug Act mandated that possession of less than 2 ounces of crack resulted in a minimum sentence of ten years in prison. A defendant caught with powder cocaine would have to possess 11 pounds of the drug to receive that same ten-year term.

Over time, a collection of scientific studies of drug addiction determined that there was little difference between the two forms of cocaine. Judges, and even some prosecutors, also took to publicly lamenting the lengthy prison terms they were forced to impose. Congress took notice. Passing the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, legislators reduced the steep mandatory minimums for crack to achieve more parity among drug sentences. But that law did not fix the sentences of those already in prison.

Then in 2014, the tide began to turn. On April 10, the U.S. Sentencing Commission voted unanimously to reduce sentences for drug offenders, and Congress agreed to apply the new guidelines retroactively. Thirteen days later, the Obama administration launched a “Clemency Initiative,” asking lawyers to help find incarcerated people who were serving unjustly long sentences for non-violent drug crimes. Bi-partisan bills began getting introduced in Congress that called for lower penalties and better treatment programs for drug users. Democrats and Republicans began talking about reforming the sentencing of non-violent drug offenders. Although a reform bill introduced by a bi-partisan group of senators on Oct. 1, 2015, is still making its way through Congress, it has wide support. Nearly all of the 2016 presidential candidates have spoken out in favor of sentencing reforms.

SOURCES: U.S. Department of Justice

Shauna Barry-Scott is one of the lucky ones. As a result of the Clemency Initiative, President Barack Obama commuted the last 10 years of her sentence, and set her free. In response, she plans to dedicate her new life to future generations by becoming a motivational speaker.

“I have some incredible information to share with them,” she says. Her goal is to help at-risk children avoid the mistakes she made and, “Make something out of their lives. We’ve got a lot of problems in the inner city, and solutions can only come from within. I’m just happy to have this second chance, and I can’t wait to get started.”

Published on October 29, 2015

Additional Credits

Coordinating Producer DEVIN DWYER

Executive Producer DAN SILVER

Managing Editor XANA O'NEILL

Supervising Producer RONNIE POLIDORO

Creative Design Director LORI NEUHARDT

Interactive Designer JAN DIEHM

Senior Developer GREG ATRIA

Additional Camera JUSTINE QUART

Booker ROBIN GRADISON

When the ill-fated “War on Drugs” was launched 29 years ago, the campaign swept up hundreds of thousands of Americans and put them in prison. The Anti-Drug Abuse Act signed by Ronald Reagan in 1986 codified a mindset of “Just Say No to Drugs,” a mantra that inspired a movement toward harsher punishment as the best deterrent to the sale and use of illicit drugs.

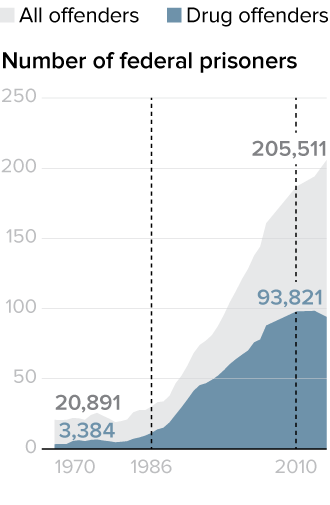

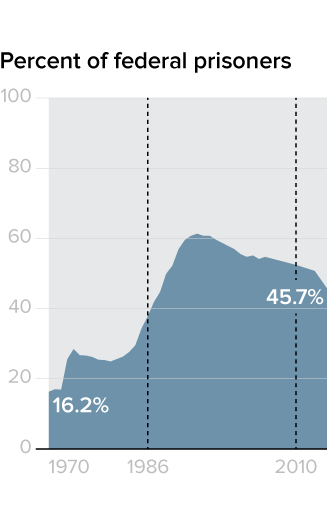

A Prison Population Boom

When the Anti-Drug Act of 1986 became law, the number of federal prisoners rose dramatically. Drug-related offenders increased to more than half of the total population. As the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 began to take hold, the percentage of drug offenders began to decline. However, many are still serving lengthy prison terms under the old law.

NOTE: Federal prisoners only includes the sentenced population.

SOURCES: U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Prisons, Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics

Mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses took judges out of the equation. No longer would they have the discretion to send low-level offenders to drug treatment programs, as was the common practice prior to this Act. The law took direct aim at crack cocaine, under the misguided belief that it was a far more dangerous substance than cocaine in its powder form. The Anti-Drug Act mandated that possession of less than 2 ounces of crack resulted in a minimum sentence of ten years in prison. A defendant caught with powder cocaine would have to possess 11 pounds of the drug to receive that same ten-year term.

Over time, a collection of scientific studies of drug addiction determined that there was little difference between the two forms of cocaine. Judges, and even some prosecutors, also took to publicly lamenting the lengthy prison terms they were forced to impose. Congress took notice. Passing the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, legislators reduced the steep mandatory minimums for crack to achieve more parity among drug sentences. But that law did not fix the sentences of those already in prison.

Then in 2014, the tide began to turn. On April 10, the U.S. Sentencing Commission voted unanimously to reduce sentences for drug offenders, and Congress agreed to apply the new guidelines retroactively. Thirteen days later, the Obama administration launched a “Clemency Initiative,” asking lawyers to help find incarcerated people who were serving unjustly long sentences for non-violent drug crimes. Bi-partisan bills began getting introduced in Congress that called for lower penalties and better treatment programs for drug users. Democrats and Republicans began talking about reforming the sentencing of non-violent drug offenders. Although a reform bill introduced by a bi-partisan group of senators on Oct. 1, 2015, is still making its way through Congress, it has wide support. Nearly all of the 2016 presidential candidates have spoken out in favor of sentencing reforms.

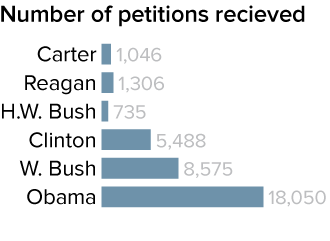

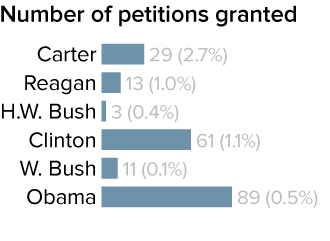

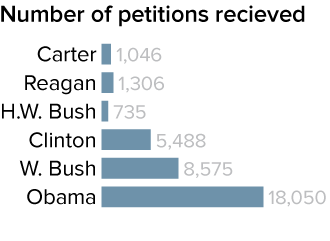

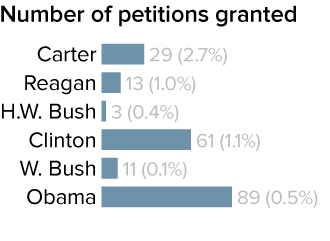

Commutations By President

Since Jimmy Carter’s presidency in 1977 the White House has received 35,201 petitions for commutations. Only 206, or 0.6 percent have been granted.

SOURCES: U.S. Department of Justice

Shauna Barry-Scott is one of the lucky ones. As a result of the Clemency Initiative, President Barack Obama commuted the last 10 years of her sentence, and set her free. In response, she plans to dedicate her new life to future generations by becoming a motivational speaker.

“I have some incredible information to share with them,” she says. Her goal is to help at-risk children avoid the mistakes she made and, “Make something out of their lives. We’ve got a lot of problems in the inner city, and solutions can only come from within. I’m just happy to have this second chance, and I can’t wait to get started.”

Published on October 29, 2015

Additional Credits

Coordinating Producer DEVIN DWYER

Executive Producer DAN SILVER

Managing Editor XANA O'NEILL

Supervising Producer RONNIE POLIDORO

Creative Design Director LORI NEUHARDT

Interactive Designer JAN DIEHM

Senior Developer GREG ATRIA

Additional Camera JUSTINE QUART

Booker ROBIN GRADISON